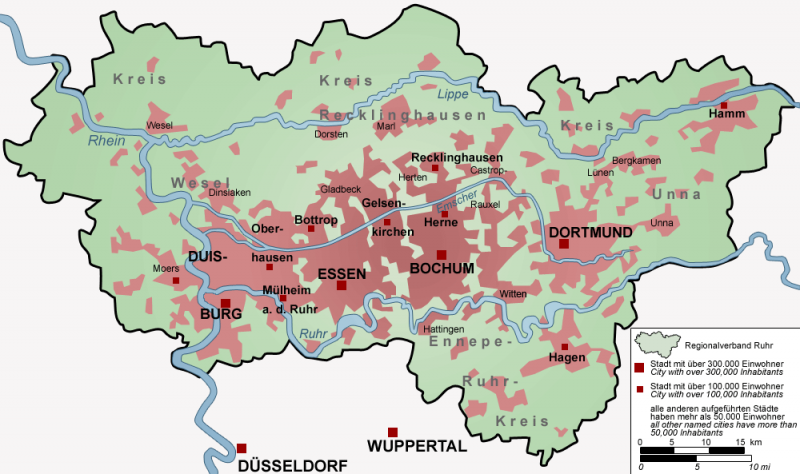

The Ruhrgebiet in Germany

The Ruhrgebiet in Germany

2009 TUBS

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

As the Ruhr region became the industrial center of Europe during the latter decades of the nineteenth century, coal mining and heavy industry swiftly encroached on the Emscher valley, causing subsidence and disrupting the river Emscher’s drainage systems. Floods intensified the threat that heavily polluted waters posed to a growing and increasingly dense population. The Emschergenossenschaft (Emscher Cooperative), founded in 1899 and something of a precedent setter for future ‘riparian cooperatives’ (Cioc 2002: 82), responded at the beginning of the twentieth century by straightening the Emscher’s lower reaches, canalizing its tributaries, and building dykes. The best part of a century later, the same Cooperative oversaw a project that signalled an about turn: the renaturalization of the Emscher.

The Ruhr region in detail (the Emscher flows through the center)

The Ruhr region in detail (the Emscher flows through the center)

2004 Threedots (Daniel Ullrich)

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Valued at € 4.4 billion, this is one of the largest projects of its kind in Europe. An international construction exhibition opened in 1989, and plans for the Emscher Landscape Park emerged. A diverse mixture of civic, regional and European backing flowed in and, by 2010, a large-scale public art exhibition had appeared on the Emscher Island. The island itself is the product of a previous landscape transformation event, namely, the Rhine-Herne Canal, completed in 1914. A case of infrastructure, environmental, and art history in the making, this confluence of events provides much food for thought with regard to the relationship between environment and society.

Contemporary artists displaying works at Emscherkunst.2010 (29 May–18 September) found various ways of reflecting upon the chosen site. Beginning at the eastern end of the Island and travelling west, Mark Dion (USA) converted an old gas tank into an observation station looking out on the Herne Sea, complete with information on the lake’s native species.

Society of Amateur Ornithologists by Mark Dion (2010)

Society of Amateur Ornithologists by Mark Dion (2010)

The work further explores several themes that reoccur in Dion’s ouvre, regarding which, the observation station (Blind/Hide: The Mobile Birding Unit, 2000) at the Tijuana River Estuary Reserve on the Mexico-United States border is a case in point. All rights reserved © Roman Mensing / EMSCHERKUNST.2010. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Inside Dion’s Society of Amateur Ornithologists. Many of the items that furnish the hide were sourced from local flea markets.

Inside Dion’s Society of Amateur Ornithologists. Many of the items that furnish the hide were sourced from local flea markets.

All rights reserved © Roman Mensing / EMSCHERKUNST.2010. Used by permission.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Walking House by N55 (2010), seen here at the former site of the Nordstern Mine in Gelsenkirchen.

Walking House by N55 (2010), seen here at the former site of the Nordstern Mine in Gelsenkirchen.

Please click here for the manual that accompanies this work.

All rights reserved © Roman Mensing / EMSCHERKUNST.2010. Used by permission.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

It would be hard to imagine a more striking contrast to the tenor of much of the Emscher valley’s environmental history over the past two centuries than the description of Walking House in the work’s ‘manual’: “a modular dwelling system that enables persons to live a peaceful nomadic life, moving slowly through the landscape or cityscape with minimal impact on the environment.” The tongue-in-cheek approach may well help rather than hinder serious thinking about collecting rainwater, growing one’s own food, solar-heated hot water, composting toilets, and CO2 neutral heating. Creator N55, a Danish artists’ group, has provided for all of these.

Observatorium’s Waiting for the River (2010).

Observatorium’s Waiting for the River (2010).

Since 1997, the artist group Observatorium is commited to create relationships between art, landscape and society.

All rights reserved © Roman Mensing / EMSCHERKUNST.2010. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Rotterdam-based artists’ group Observatorium incorporated their characteristic concern for relations between art, landscape, and society in Waiting for the River. A wooden bridge of approximately 38 meters long, housing three pavilions, provided space to reflect upon the prospect of the renaturized river flowing through the site, once the Emscher conversion project completes. Visitors also had the option of staying overnight.

Inside Observatorium’s Waiting for the River

Inside Observatorium’s Waiting for the River

All rights reserved © Roman Mensing / EMSCHERKUNST.2010

Used by permission.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Observatorium’s Waiting for the River, inviting contemplation

Observatorium’s Waiting for the River, inviting contemplation

Located at Essen-Altenessen, by the mouth of the Schwarzbach, northeast of the Schurenbach Mine waste heap.

All rights reserved © Billie Erlenkamp / EMSCHERKUNST.2010. Used by permission.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

From a site exhibiting the scars that extractive industries left behind to one where interested parties congregate to exchange knowledge and ideas on an altogether different future: could this be indicative of the kinds of landscape transformation and cultural shifts required to stem the tide of other, yet more threatening environmental crises?

The author would like to thank Regina Sasse for her talk on Emscherkunst.2010 at FORUM TutzingKultur, which inspired him to explore the Emscher valley further.

How to cite

Tendler, Ben. “The Culture of Landscape Transformation: From an Off-Limits, Open Sewer to the New Emscher Valley.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2012), no. 17. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/3927.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2012 Ben Tendler

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Blackbourn, David. The Conquest of Nature: Water, Landscape, and the Making of Modern Germany. New York: W. W. Norton, 2006.

- Cioc, Mark. The Rhine: An Eco-Biography 1815–2000. Weyerhaeuser Environmental Books. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2002.

- DVWK Deutscher Verband für Wasserwirtschaft und Kulturbau e.V., ed. Ökologische Erneuerung einer Industrielandschaft. Schriftenreihe des Deutschen Verbandes für Wasserwirtschaft und Kulturbau. Heft 108. Bonn: Wirtschafts- und Verlagsgesellschaft Gas und Wasser, 1994.

- Emschergenossenschaft, and Ralf Peters, eds. 100 Jahre Wasserwirtschaft im Revier: Die Emschergenossenschaft 1899-1999. Bottrop: Pomp, 1999.

- Emschergenossenschaft, Regionalverband Ruhr, and Observatorium, eds. Warten auf den Fluss: Das Neue Emschertal im Wandel der Kunst. Ein Lesebuch. [Waiting for the River: The New Emscher Valley in the Transformation of Art. A Reader.] With texts by Eberhard Geisler, Florian Matzner, Observatorium, Martina Oldengott, Regina Sasse, Paul Shepheard, Jochen Stemplewski, and Simone Timmerhaus. Essen: Klartext, 2011.

- Kurowski, Hubert. Die Emscher. Geschichte und Geschichten einer Flusslandschaft. Essen: Klartext, 1993.

- Matzner, Florian, Karl-Heinz Petzinka, and Jochen Stemplewski, eds. Emscherkunst.2010: Eine Insel für die Kunst. [Emscherkunst.2010: Eine Insel für die Kunst] Published in conjunction with the exhibition of the same name. Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2010