The interwoven relationship between people, plants, and place has shaped the earth’s ecology beyond the temporal span of our archives. However, centuries of European colonialism and the capitalist system it birthed (dependent on monoculture plantations and the commodification of life) has, with time, strained the interspecies fabric of life on earth to the point of what Deborah Bird Rose termed an unraveling. Similarly, the metaphor of “plant blindness” has gained momentum in recent years, expressing growing concerns about a cognitive disconnect in which plants and human reliance on them slip from view. In this context, botanical collections and their history of public display—peaking in nineteenth-century botanical museums—provides the environmental historian with a valuable record. This article follows a nineteenth-century economic-botany collection in Florence, Italy, from public display to botanical research collection, as an eloquent witness to this global reshaping in what was then a new nation within colonial networks but, as yet, without colonies.

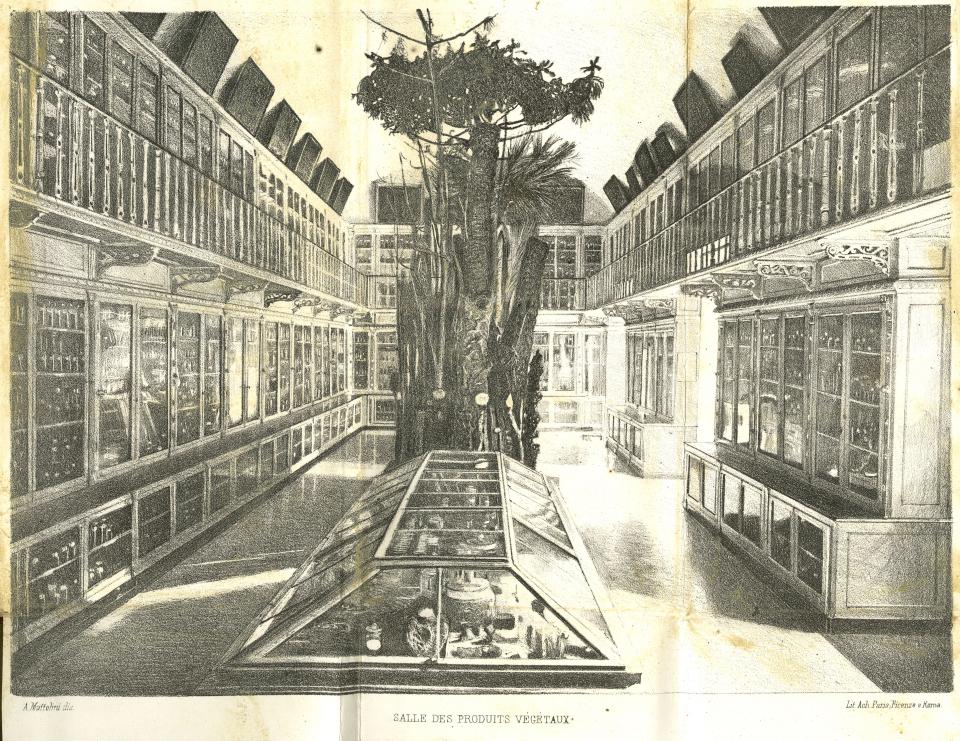

Figure 1. A print of the gallery of vegetable products from Filippo Parlatore’s 1874 catalogue Les Collections Botaniques du Musée Royal de Physique et d’Histoire Naturelle de Florence.

Figure 1. A print of the gallery of vegetable products from Filippo Parlatore’s 1874 catalogue Les Collections Botaniques du Musée Royal de Physique et d’Histoire Naturelle de Florence.

Philippe Parlatore, Les Collections Botaniques du Musée Royal de Physique et d’Histoire Naturelle de Florence au Printemps de MDCCCLXXIV, (Florence, 1874; anastatic reprint, 1992).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 1874, Filippo Parlatore (1816–1877), professor of botany, published a comprehensive catalogue of the collections of the Botanical Museum in Florence, which was part of the famous Royal Museum of Physics and Natural History founded in 1775. Alongside herbaria, wax models, fossils, living collections, and a library, Parlatore dedicated a large section of the catalogue to the provenance, display, and contents of the vegetable products collection, which he described as unrivalled “except for the rich collection at Kew, made with the formidable means available to Great Britain, mistress of much of the earth” ([1874] 1992, 61; author’s translation). Botany, art, and industry merged in this gallery (figure 1). The objects were arranged botanically according to “natural families” and meticulously labelled, and Parlatore emphasized that they were always displayed alongside the “natural products” of the plant from which they were derived, so that visitors could “immediately see” the connection for themselves. Of these visitors, he repeatedly mentions the traveler, reflecting the geographical scope of the collection beyond the region and nation. Although it contained cultural objects arranged according to a public pedagogy of display, Parlatore clearly considered this a scientific collection: in a telling footnote he referred to fuller discussions of the vegetable products in his forthcoming “Géographie botanique” (which was never published). Parlatore was an avid follower of Alexander Humboldt’s geographical approach, and when his own ambitions of global scientific travel were dashed, he focused his efforts on collecting at a global scale, bringing the world to him by enlisting the help of diplomatic, commercial, and private contacts operating within the entangled global networks of trade and empire.

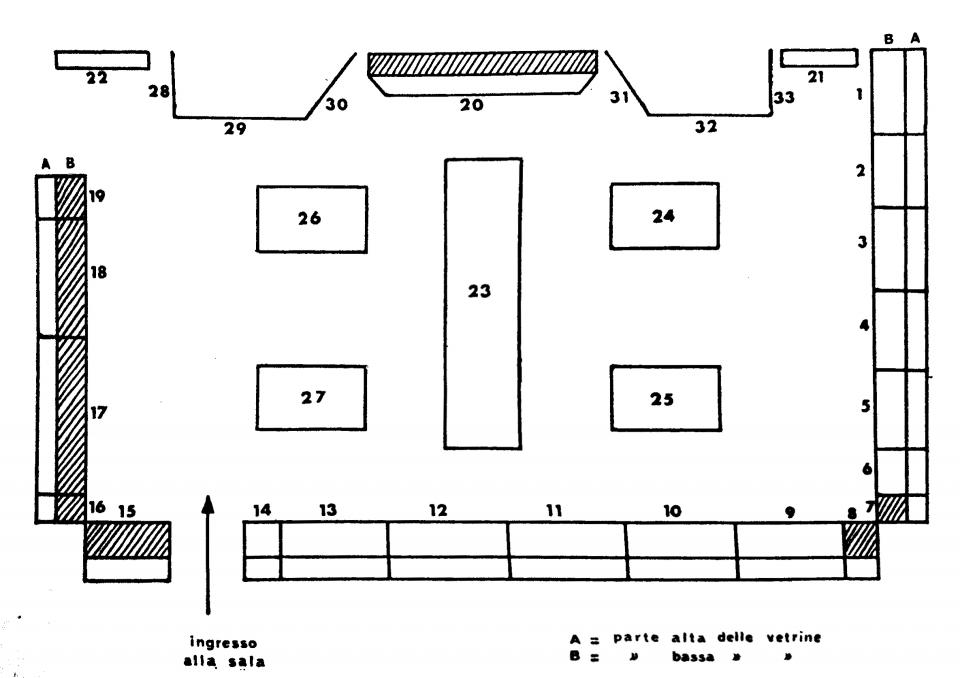

Figure 2. Map of the botanical exhibition from the 1976 visitor’s guide. Today, the displays from cabinets 6–8 and 13–20 remain intact or partially intact.

Figure 2. Map of the botanical exhibition from the 1976 visitor’s guide. Today, the displays from cabinets 6–8 and 13–20 remain intact or partially intact.

Courtesy of the Natural History Museum of Florence.

Guido Moggi, Una visita al museo botanico dell-università degli studi di Firenze (Firenze: Museo botanico dell’università degli studi di Firenze, 1979).

Used with permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Figure 3. The pharmaceutical cabinet brings together “prodotti vegetali” and herbarium specimens for several important drugs, including cannabis, marijuana, and opium. The cotton cabinet depicts the process of production from plant to commodity, from the cotton pods to woven fabric, following the same progression as the linen display in cabinet 8.

Figure 3. The pharmaceutical cabinet brings together “prodotti vegetali” and herbarium specimens for several important drugs, including cannabis, marijuana, and opium. The cotton cabinet depicts the process of production from plant to commodity, from the cotton pods to woven fabric, following the same progression as the linen display in cabinet 8.

Photograph by Anna Svensson.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Parlatore’s death in 1877 was followed by the fragmentation of the botanical collections—a departure from the vision of scientific universality and public pedagogy on which the museum had been founded. With the unification of Italy, the collections increasingly reflected the needs of national natural history and centralized scientific research. A research institute, which later became part of the University of Florence, was founded within the museum, organized into six departments, some of which were later relocated to other parts of the city. In the early 1880s, the botanical collections were controversially moved to their current location near San Marco

In the new location, the herbarium was expanded while the botanical collections on public display were concentrated in a single room. A visitor’s guide from 1976 provides a valuable overview of its organization and pedagogy (figure 2). It includes material familiar from Parlatore’s description—notably the cabinets on cotton and linen displaying the steps of production from plant to fabric (figure 3)—as well as updated additions including evolution and conservation. In contrast to Parlatore’s ambition towards universality or completion, this guide to the downsized museum apologetically claims that it cannot cover all aspects of botany. Instead, it offers a set of perspectives through which the visitor can explore the collections—an approach that is nonlinear and multilayered.

Figure 4. The “carpotheque” collections (continuing in the following room) housed in 33 gallery cabinets above the comings and goings in the new office spaces. Some of the palms that were displayed in the center of the Galleria dei Prodotti Vegetali are visible by the door.

Figure 4. The “carpotheque” collections (continuing in the following room) housed in 33 gallery cabinets above the comings and goings in the new office spaces. Some of the palms that were displayed in the center of the Galleria dei Prodotti Vegetali are visible by the door.

Photograph by Anna Svensson.

From the collections of the Natural History Museum of Florence.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In the 1990s, the Botanical Museum was closed to the public (except by appointment) and partially dismantled to make way for disabled access, office space, and growing collections. Of the museum displays still intact, some are visible, some obscured or partially dismantled. After the relocation, most of the “prodotti vegetali” were subsumed into the “carpotheque” (fruit collection, sometimes extended to cover plant material that cannot be pressed) (figure 4). Although the specimens are arranged botanically according to genus, the labels are not standardized and often give the derivative substance rather than the Latin binomial. Many plants are cultivated, domesticated, and acclimatized, and sometimes the contents of the jar cannot be definitively tied to a particular species (as in the case of indigo).

Figure 5. A selection demonstrating the diversity of the “carpotheque” collection, much of which was originally displayed in the “prodotti vegetali” exhibition: a palm leaf collected by Odoardo Beccari; the flower of Tozzettia persica (in spirits) grown in the botanical garden in 1854; the photograph of a wintry forest landscape in the far north of Finland (“Torneo” and “Kittila”); a dried “coloquinte” (desert gourd) from the “Exposition Vice-Royale Egyptienne”; cotton seeds from Italy’s colony of Eritrea (1903); paper flowers made of Aralia papyrifera; a pinecone from the type Pinus soulangeana bought in London, 1862; Strychnos nux-vomica obtained in an exchange with the Museo Tecnologico, Florence, 1878; indigo “di una pianta indigena della Confed. Argentina” donated by Sig. Durrassi in February 1868; Trapa natans from the “antica collezione dei museo”; fiber and fabric from Lupinus albus; Eucalyptus globulus cigarettes from a chemist in Melbourne; and a selection of beautifully presented local Tuscan flax oil.

Figure 5. A selection demonstrating the diversity of the “carpotheque” collection, much of which was originally displayed in the “prodotti vegetali” exhibition: a palm leaf collected by Odoardo Beccari; the flower of Tozzettia persica (in spirits) grown in the botanical garden in 1854; the photograph of a wintry forest landscape in the far north of Finland (“Torneo” and “Kittila”); a dried “coloquinte” (desert gourd) from the “Exposition Vice-Royale Egyptienne”; cotton seeds from Italy’s colony of Eritrea (1903); paper flowers made of Aralia papyrifera; a pinecone from the type Pinus soulangeana bought in London, 1862; Strychnos nux-vomica obtained in an exchange with the Museo Tecnologico, Florence, 1878; indigo “di una pianta indigena della Confed. Argentina” donated by Sig. Durrassi in February 1868; Trapa natans from the “antica collezione dei museo”; fiber and fabric from Lupinus albus; Eucalyptus globulus cigarettes from a chemist in Melbourne; and a selection of beautifully presented local Tuscan flax oil.

Photograph by Anna Svensson.

Objects from the collections of the Museum of Natural History (Botany) of the University of Florence.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Although no longer formally displayed, the shelves after shelves of dormant “prodotti vegetali”—ghostly orchids under dusty glass, coagulating oils, toxic warning signs, musty pickle wafts, and the delightful surprise of eucalyptus cigarettes in their original packaging—are powerfully evocative as phenomenological encounters with the material remains of past plants, people, and places (figure 5). These encounters are important to understanding the power of the pedagogy of display behind the original exhibition—bringing together plants, plant substances, and products—that enabled visitors to forge connections with plants from distant places. Yet the socioecological consequences for these places of cultivation and production remained out of sight. Ultimately, these specimens bear eloquent witness to the role of botanical science in the efforts of emerging national economies to rationalize domestic agrarian production within the increasingly dominant forces of accelerating globalism and industrial processing, during a period just before our reliance on plants would be obscured by these same processes.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the C. M. Lerici Foundation and the Helge Ax:son Johnsons stiftelse for funding research visits to the Botanical Section of the Natural History Museum, University of Florence. In particular, I wish to thank Head Curator Dr. Chiara Nepi for so generously sharing her extensive knowledge of the collections, and Mark Nesbitt and Caroline Cornish at the Mobile Museum project at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, for providing invaluable insights into the history of economic-botany collections and their display.

How to cite

Svensson, Anna. “Recollecting the ‘prodotti vegetali’ of the Natural History Museum, University of Florence.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. 12. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9017.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Anna Svensson

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Bird Rose, Deborah. “Multispecies Knots of Ethical Time.” Environmental Philosophy 9 (2012): 127–40.

- McDonough MacKenzie, Caitlin, Sara Kuebbing, Rebecca S. Barak, Molly Bletz, Joan Dudney, Bonnie M. McGill, Mallika A. Nocco, Talia Young, and Rebecca K. Tonietto. “We Do Not Want to ‘Cure Plant Blindness’ We Want to Grow Plant Love.” Plants, People, Planet 1 (2019): 139–41. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppp3.10062.

- Nesbitt, Mark, and Caroline Cornish. “Seeds of Industry and Empire: Economic Botany Collections between Nature and Culture.” Journal of Museum Ethnography 29 (2016): 53–70.

- Parlatore, Philippe. Les Collections Botaniques du Musée Royal de Physique et d'Histoire Naturelle de Florence au Printemps de MDCCCLXXIV. Florence, 1874; anastatic reprint, 1992.

- Raffaelli, Mauro (ed.). Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell'Università di Firenze. Volume II. Le collezioni botaniche. Florence: Firenze University Press, 2009.