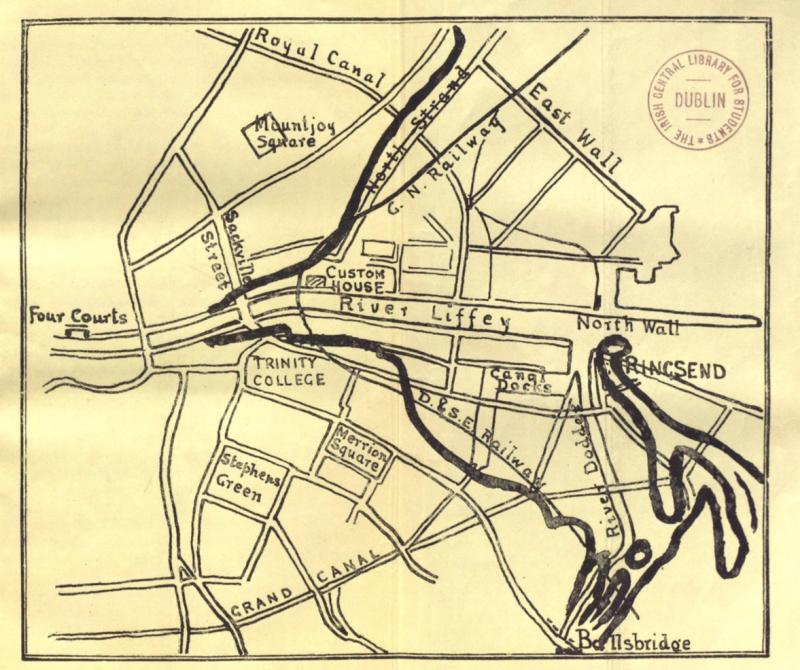

Sketch plan of Dublin showing the coastline and the isolated position of Ringsend in 1673, according to Sir Bernard de Gomme’s map. (The heavy line indicates the position of the old coastline.)

Sketch plan of Dublin showing the coastline and the isolated position of Ringsend in 1673, according to Sir Bernard de Gomme’s map. (The heavy line indicates the position of the old coastline.)

Map by W. J. Joyce, 1921.

Courtesy of the Cultural Heritage Project, Ireland.

Originally published in Joyce, The Neighbourhood of Dublin (Dublin: Gill & Son, 1921).

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Ringsend in county Dublin, Ireland, is a central part of Dublin City, iconified by the striking Poolbeg chimneys. It was once a vibrant fishing village, located on the south bank of the River Liffey and east of the River Dodder, a narrow peninsula separated from the rest of Dublin by the Dodder estuary (then much broader than in current times), yet the gateway to the capital.

Ringsend was colloquially known as “Raytown” due to the popularity of “Ringsend Ray” or stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca), an elegant fish with a boneless skeleton that seems to fly through the water with its flattened body and large pectoral fins. Stingrays belong to the elasmobranch subclass, mainly found in coastal waters and exceptionally down to three thousand meters. Generally cosmopolitan, most elasmobranchs inhabit tropical and subtropical marine environments. Ireland’s coasts are home to skates and rays, which were plentiful in Dublin Bay until the beginning of the twentieth century.

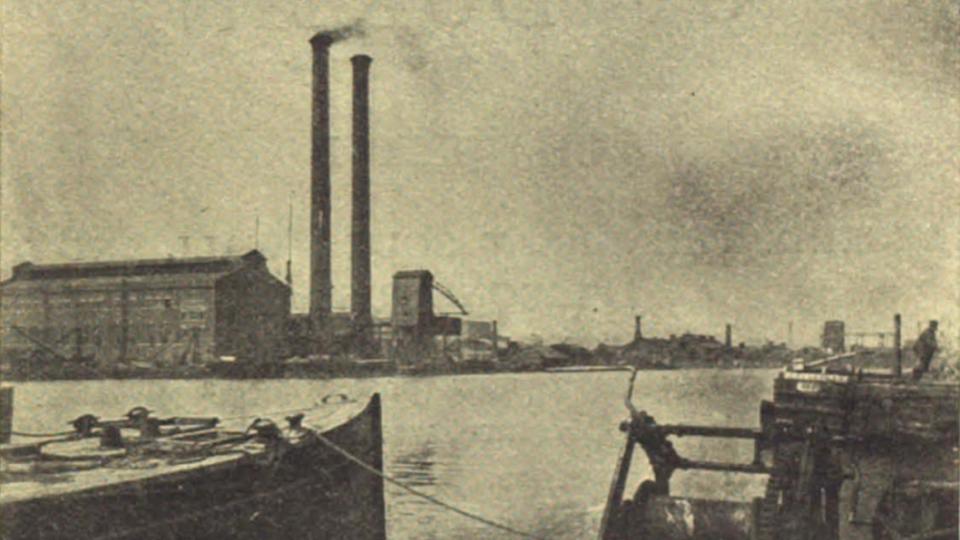

Photograph of Ringsend’s generating station in 1904.

Photograph of Ringsend’s generating station in 1904.

Photograph by W. J. Joyce, 1904.

Courtesy of the Cultural Heritage Project, Ireland.

Originally published in Joyce, The Neighbourhood of Dublin (Dublin: Gill & Son, 1921).

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Ringsend’s generating station in 2017. The Poolbeg chimneys are colloquially known as the “Poolbeg stacks.”

Ringsend’s generating station in 2017. The Poolbeg chimneys are colloquially known as the “Poolbeg stacks.”

© 2017 Cordula Scherer.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

There are good reasons why people in the past would refer to Ringsend as Raytown. Ray, indeed, played an important role in the area’s everyday life. Rejected elsewhere in Ireland, ray became a staple food for the people of Ringsend from the early nineteenth century, when it was landed as bycatch following the introduction of beam trawlers (Nairn et al., 2017). As records from the National Folklore Collection demonstrate, Ringsenders developed an intimate connection with this batoid, which was never sold but rather shared amongst the people of Ringsend. In 1980, “Lyrics” Murphy, a well-respected member of the Ringsend community, recalled the following remarkable story about “towed ray” from his childhood in the 1910s (UFP0482, 1980):

It was common practice that fishermen gutted the rays they caught in the last haul—only the last haul you see—cut off the wings, skinned both sides—you know Ringsend people don’t eat ray with only one side skinned. They’d get a few dozen wings together to get them fast on a log line and put them over the side—you’d make a half hitch through the wings and then you towed them through the seawater to the home port for some 13 odd miles. This made the meat tender and gave it a beautiful flavour. Then, you’d put the wings on the line between the houses of our narrow streets and after 4–5 days the drying ray would become “pissy” (smelling strongly of ammonia). This was a distinctive smell in Ringsend. You needed to let the sun and wind get to them to dry them properly and you’d have wing for 6 months or more. We often ate it seven days a week—you see we couldn’t afford anything else. Hunger was a good sauce in those days.

The common stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca).

The common stingray (Dasyatis pastinaca).

Photograph by Glen Bowman, 2007.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 27 October 2020. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Bob Gray, born in 1911, recalls another childhood story about Ringsend’s ray (UFP00089, 1980):

An old fisherman cured a child’s weak limbs with buckets of small rays. The child was unable to walk, you see, and no doctor could help her. So the fisherman told the mother he’d help her. He boiled up ray skin into a jelly, gave the child ray water to drink and ray meat to eat. He massaged her weak limbs with the jelly every day for 2 weeks, you see, 2 weeks. After that the girl was running around happy and cheerful with the other children, just her legs were covered in blonde hair—hairy like a fella.

Curiously, the healing powers of ray and skates were known well beyond Ringsend. Other sources from the National Folklore Collection mention, for instance, that “local burns should be treated by rubbing the oil that comes out of a skate onto the affected area and it’ll disappear.” British zoologist Francis Day noted in his 1880 book The Fishes of Great Britain and Ireland that Welsh fishers used ray-liver oil as a treatment for burns and other injuries.

A worked stingray barb. This image was slightly modified for the purpose of this publication.

A worked stingray barb. This image was slightly modified for the purpose of this publication.

Detail from photograph by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Accessed via Wikimedia on 27 October 2020. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

How can we make sense of these forgotten local practices? Do these elasmobranchs indeed have healing powers? Stingrays are venomous fish, but since their venom is stored within tissue cells and has a complex secretion mechanism, scientific studies of it are limited. It is known, however, that stingray toxins induce cell death and inhibit defense enzymes in victims. In humans, this leads to increased blood flow in the superficial capillaries and cell death. This, maybe, suggests an explanation for the historical description of the ray’s healing powers. The fact that stingray venom is stored in tissue cells rather than in glands might explain why the girl’s weak legs were healed after being treated with ray jelly, which possibly helped the blood flow in her legs. There is also evidence that the innate immune system of elasmobranchs produces anti-bacterial properties, which might explain why people used ray-liver oil to treat local burns and other injuries.

It has been a while since stingray abounded in Dublin Bay. In 2009, the International Union for Conservation of Nature assessed common stingray as “Near Threatened” in the entire Bay of Biscay and an EU ban on coastal trawling protects their habitat now, while most International Council for the Exploration of the Sea divisions have prohibited elasmobranch fishing since 2018 (EU 2018/120). Raytown and towed ray are history, but many grandchildren of seafaring families in Ringsend still remember their parents telling stories about fishing for crabs off the quay with the backbone of a ray. Listening to them takes us into a world in which humans and local environments were very intimately linked.

Acknowledgment

This article was completed during the Irish Research Council COALESCE funded project 2019/97.

How to cite

Scherer, Cordula. “The Remarkable Ray of Dublin’s Ringsend.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2020), no. 41. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9150.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Cordula Scherer

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Joyce, Weston St. John. The Neighbourhood of Dublin: Its Topography, Antiquities and Historical Associations. 2nd ed. Dublin: Gill & Son, 1921.

- Day, Francis. The Fishes of Great Britain and Ireland. 2 vols. London: Williams and Norgate, 1880–1884.

- Dos Santos, Janaina Cardoso, Lidiane Zito Grund, Carla Simone Seibert, Elineide Eugênio Marques, Anderson Brito Soares, Valerie F. Quesniaux, Bernhard Ryffel, Monica Lopes-Ferreira, and Carla Lima. “Stingray Venom Activates IL-33 Producing Cardiomyocytes, but Not Mast Cell, to Promote Acute Neutrophil-Mediated Injury.” Scientific Reports 7, no. 1 (2017): 7912. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-08395-y.

- Nairn, Richard, David Jeffrey, and Rob Goodbody. Dublin Bay: Nature and History. Doughcloyne, Wilton, Cork: Collins Press, 2017.

- Serena, Fabrizio, Cecilia Mancusi, Gabriel Morey, and Jim R. Ellis. Dasyatis pastinaca. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2009: e.T161453A5427586. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2009-2.RLTS.T161453A5427586.en.

- Official Journal of the European Union. COUNCIL REGULATION (EU) 2018/120 January 2018.