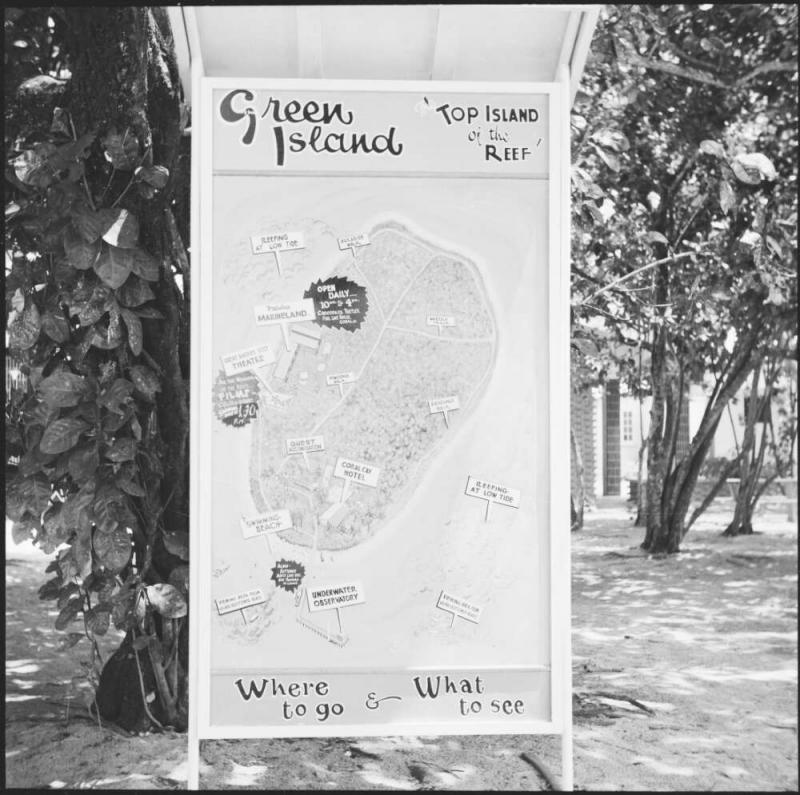

Green Island map showing locations of the underwater observatory and Marineland Melanesia, 1963.

Green Island map showing locations of the underwater observatory and Marineland Melanesia, 1963.

© National Library of Australia.

Tourist information sign and map, Green Island, Queensland.

Photograph by Michael Terry, 1963.

Click here to view source.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Australia is a diverse continent, but its population is largely concentrated in its southeast corner. Tropical Australia is a place apart from the southern cities of Melbourne, Sydney, Adelaide, and even Queensland’s capital, Brisbane. In the period after the Second World War, a group of tourism entrepreneurs presented the Australian tropics (particularly northern Queensland and the Top End of the Northern Territory) to southern Australians and international visitors as an adventure playground, distant from their suburban realities. The Australian Crocodile Shooters’ Club, and its offshoots and successors, used crocodiles to lure tourists to northern Australia, exploiting widespread human fascination with “man-eating” species to establish tourism enterprises.

The Australian Crocodile Shooters’ Club was founded in 1950 by a French-born, Melbourne-based ladies’ hairdresser. Rene Henri was an enthusiastic big game hunter, as well as an entrepreneur who used the contrast between his two main business interests to good effect. The Club, and Henri’s promotion of big game hunting within Australia, clearly sought to draw southern Australians north. In skilfully arranged press coverage of Club dinners in the southern cities and of crocodile hunting trips along the northern Queensland coast, Henri promoted the possibility of reaching the north comparatively quickly and enjoying the crocodile-based adventures it had to offer. This ability to travel into remote Australia using newly available air transport and road infrastructure marked a new epoch in northern tourism, which had begun in the late 1940s and which Henri sought to develop.

The Australian Crocodile Shooters’ Club base in the Gulf of Carpentaria, 1952.

The Australian Crocodile Shooters’ Club base in the Gulf of Carpentaria, 1952.

Photograph by Charles Daniel Pratt, 1952.

Courtesy of National Library of Australia, Trove. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Henri’s club extended the tourist crocodile-hunting tours that had been offered by local hunter and entrepreneur Vince Vlasoff since 1948. Vlasoff used his boat the Tropic Seas to take paying guests north from Cairns on hunting and fishing expeditions. Henri had taken a cruise with Vlasoff in 1949, and the two men recognized an opportunity to collaborate in extending the operation. Henri’s skill at promotion attracted southern sportsmen to the north to participate in crocodile safaris, and the cruises ran for a decade. The Tropic Seas could accommodate only six paying passengers at a time, so the Club went on to establish a land base (accessible by air) at Karumba in the Gulf of Carpentaria in 1952. The Gulf Country Club was one of the earliest Australian safari camps.

Photograph of a crocodile hunter posing with a dead crocodile at Timber Creek in the Northern Territory, 1951.

Photograph of a crocodile hunter posing with a dead crocodile at Timber Creek in the Northern Territory, 1951.

Unknown photographer, 1951.

Courtesy of the Northern Territory Library.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Another cruise customer who became a valuable business partner for Vlasoff was Lloyd Grigg, who took a Club cruise in 1952. Vlasoff invited Grigg to join him in the development of an underwater observatory on Green Island, off Cairns in far north Queensland. The observatory operated between 1954 and 2012, and while it did not directly connect northern tourism with crocodiles, Vlasoff and Lloyd extended their tourism operations on the island in a way that did. In 1960 the pair opened Marineland Melanesia, an attraction that continues to display nautical memorabilia, fish in tanks, and large crocodiles in cages.

The opening of Marineland Melanesia marked a shift in Vlasoff’s approach to crocodile tourism. Crocodiles had long been sent south to zoos; now southerners were able to travel north to see crocodiles at home. Earlier, Townsville’s Mount St John Zoo had used captive crocodiles as a tourism drawcard but its decline in the early 1950s left the field open for a new generation of crocodile entrepreneurs to capitalize on northern Australia’s new accessibility and to create forms of northern crocodile tourism to be enjoyed by family groups rather than hunters.

Vlasoff, Henri, and Grigg were crocodile entrepreneurs of the 1940s and 1950s who established a promotional pattern that persists into the present. They were pioneers of safari tourism in northern Australia, and while the Gulf Country Club only operated briefly, other safari camps followed. In the Northern Territory, Connellan Airways ran a safari operation at Wildman River Station between 1948 and 1950, Allan Stewart established the Nourlangie safari camp in 1959, and by the 1970s four camps operated in the Jim Jim Creek/Nourlangie area. Safari camps continue to operate in the Northern Territory, although after Australian crocodiles were granted full protection, the camps turned to other prey species. However, the development of crocodile farming as a successor to crocodile hunting has created other crocodile tourism opportunities. Many Australian crocodile farms include tours as part of their business model, and tourism in the Top End continues to promote the presence of crocodiles.

Tourist visiting Koorana Crocodile Park in tropical Queensland, 2018.

Tourist visiting Koorana Crocodile Park in tropical Queensland, 2018.

Photograph by Colin O’Donnell, 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

A monument featuring Steve Irwin (and crocodile) on the Sunshine Coast road named in his memory, 2019.

A monument featuring Steve Irwin (and crocodile) on the Sunshine Coast road named in his memory, 2019.

Photograph by Colin O’Donnell, 2019

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Australia’s tropical north remains associated with crocodiles. The 1986 movie Crocodile Dundee remains a part of popular culture: over 30 years after it was first released, it remained recognizable enough to be used in a major 2018 Australian tourism marketing campaign that spruiked a spoof sequel. The movie, and the marketing, present northern Australia as an adventurous, remote (yet accessible) location framed by its association with the saltwater crocodile. The same connection between masculine adventure and the landscape and fauna of northern Australia is essential to Steve “Crocodile Hunter” Irwin’s continuing popularity. The zoo he founded is located south of the saltwater crocodile’s natural range, but the association between his conservation work, television and movie productions, and the adventurous landscape of crocodile country has not been derailed by that geographic challenge (or his death). Crocodiles continue to lure visitors north, following a pattern successfully established in the late 1940s and early 1950s by early crocodile entrepreneurs.

How to cite

Brennan, Claire. “Tropical Australia’s Crocodile Entrepreneurs.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2019), no. 4. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8584.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Claire Brennan

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Berzins, Baiba. Australia’s Northern Secret: Tourism in the Northern Territory, 1920s to 1980s. Glebe, NSW: Baiba Berzins, 2007.

- Brennan, Claire. “‘An Africa on Your Own Front Door Step’: The Development of an Australian Safari.” Journal of Australian Studies 39, no. 3 (2015): 396–410. doi:10.1080/14443058.2015.1052833.

- Brennan, Claire. “Australia’s Northern Safari.” M/C Journal 20, no. 6 (2017): 1–3 (Link).

- Peach, Bryan. Crocodile Men: History and Adventures of Crocodile Hunters in Australia. Cairns: Universal Enterprises Pty Ltd, 2000.

- Quammen, David. Monster of God: The Man-Eating Predator in the Jungles of History and the Mind. New York: W. W. Norton, 2004.

- Styan, Anthony. “Townsville's Mount St John Zoo.” Queensland Historical Atlas, (2015): 1–3 (Link).