Stingless bee apiary of Zutut’ha community, Yucatan.

Stingless bee apiary of Zutut’ha community, Yucatan.

Photograph by Olea Morris.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Walking through the neotropical forests of Mexico’s Yucatan peninsula today, encountering a feral colony of Melipona beecheii—a particular kind of native, stingless bee—would be highly rare. Most extant colonies are kept by a dwindling number of local practitioners, and those that still live in the forest are highly elusive, pollinating only the highest levels of forest canopy. Yet these bees, called xunáan kab (“lady bee”) in Mayan, are living metronomes, embodying forest histories and marking out ecological time in distinctive ways.

The history of xunáan kab is tied to the regional landscape, both socially and ecologically. Pre-Colombian Maya communities held the xunáan kab bee in esteem for millennia, integrating the small insects into their mythology and understanding of cosmic order, and relying on their honey as a nutritious food staple. The shape of the hive itself—tapered stacks of horizontal brood comb, separated by small pillars of wax and resin—resemble pyramids with broad bases; one of the local beekeepers I speak with mentions the bees themselves inspired the construction of the Classic Maya pyramids. There is some irony to the fact that the Mayan city and “Wonder of the World” Chichen Itza should receive so many annual visitors, when perhaps the world’s oldest extant pyramid-building culture resides only kilometers away in an apiary only kilometers away.

Interior of xunáan kab hives, showing formation of brood comb.

Interior of xunáan kab hives, showing formation of brood comb.

Photograph by Olea Morris.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The story of ecological destruction and colonization in Yucatan has been narrated through the lives of nonhuman species before. Yet the species that get to tell these stories are often the ones that make the biggest impact, with easily distinguishable introduction events or punctuated bursts of ecological disturbance. One of these is henequen, a kind of agave that became highly valuable for its use as a fiber. In the late 1800s, much of the old-growth forest of the central peninsula was cleared to make way for vast monocultures of the plant. The boom (and subsequent bust) of “King Henequen” continues to dominate the version of regional history that most tourists to the region encounter, with plantation tours and Merida’s neoclassical architecture the most conspicuous memorials to Yucatan’s “golden age.”

Garden plots in central Yucatan in dry season.

Garden plots in central Yucatan in dry season.

Garden plots in central Yucatan in dry season.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In contrast, the story of xunáan kab is one of quiet resistance—a steady hum from the margins of the forest. It may have been on account of xunáan kab, for instance, that the European honeybee (Apis mellifera) was not introduced to the Yucatan peninsula until the mid-twentieth century, centuries after its introduction by the Spanish to other regions in Mexico. The abundance of xunáan kab hives, allowing for the steady supply of honey and wax as forced tribute to the colonizers, negated the need for their replacement or supersedence with other introduced species. In this respect, xunáan kab is a ghost of ecologies yet to be, a vanguard against unrealized ecological destruction.

Encountering ecological history through xunáan kab is a regular occurrence for the beekeepers of the Zutut’ha ecovillage, an environmentalist collective that relocated from Mexico City to rural Yucatan in 2015 to found an agroecology education center and sustainable community. The residents of the collective decided to cultivate the bees in order to sell their highly-prized medicinal honey, but also as a deliberate act of alliance-building with local communities.

View of the Temple of Kukulcan at the Chichen Itza archaeological site.

View of the Temple of Kukulcan at the Chichen Itza archaeological site.

Photograph by Olea Morris.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The beekeepers of Zutut’ha are only one thread of a larger regional struggle in which indigenous communities and meliponicultores (keepers of the xunáan kab) have long been involved, especially with regard to the region’s biocultural heritage. Though the practice of meliponicultura has gradually declined, it has by no means disappeared—while some beekeepers have begun to care for European honey bees for the significant quantity of honey produced, many persist in cultivating native bees, sharing hive divisions among close contacts. Recently, there has been renewed interest in the medicinal properties of xunáan kab honey, and honey tastings and meliponicultura workshops have emerged in response, aiming to meet tourists’ curiosities about the mysterious bees without stingers.

Yet as newcomers to the region, aside from the practice of meliponicultura, the success of Zutut’ha community’s beekeeping operation and their broader mission to produce food in ways that minimize harm to the local environment hinge on their relationships with local experts. Adopting meliponicultura connects the collective to their Maya neighbors through a shared history of practice, including sharing hives to allow beekeepers to propagate new colonies and trading tips about pest control.

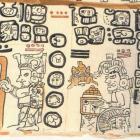

A selection from page 108 of a copy of the Madrid Codex, depicting the cultivation of native bees [bottom right].

A selection from page 108 of a copy of the Madrid Codex, depicting the cultivation of native bees [bottom right].

Courtesy of Foundation for the Advancement of Mesoamerican Studies (FAMSI).

Image taken from Léon de Rosny’s 1883 compilation. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The decline of the health of the forests leaves the future of xunáan kab uncertain. This decline is shaped by more irregular blooming periods caused by climate change, the widespread use of pesticides, and deforestation caused by the encroachment of industrial agriculture plots and touristic development projects. At times, this perceived precarity seems to justify adaptations from more traditional beekeeping methods. For example, using rectangular hives with removable lids instead of the more traditional jobones—hollowed tree trunks which are stopped at the ends—becomes necessary to more effectively combat mites and support hive populations without damaging the wax structures, I’m told.

One morning in March, I awoke to a buzzing sound so deafening I was sure that my tent was enveloped in a swarm of bees. Tentatively unzipping my tent flap, I was puzzled to find there were no bees in sight; the sound was of a colony reverberating from somewhere high in the canopy above. As other species have come and gone, leaving deep marks on the landscape only to be slowly erased, will xunáan kab continue keeping time from somewhere just beyond our reach?

How to cite

Morris, Olea. “Xunáan Kab Rhythms: Native Bees and Ecological Change in Yucatan, Mexico.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2020), no. 36. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9130.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Olea Morris

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Calkins, Charles Franklin. “Beekeeping in Yucatan: A Study in Historical-Cultural Zoogeography.” PhD diss., University of Nebraska–Lincoln, 1974. ETD collection, AAI7423880. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/dissertations/AAI7423880.

- Echazarreta, Carlos M., Javier J. G. Quezada Euán, Luis M. Medina, and Katherine L. Pasteur. “Beekeeping in the Yucatan peninsula: development and current status.” Bee World 78, no. 3 (1997): 115–127.

- Quezada-Euán, José Javier G. Stingless Bees of Mexico: The Biology, Management and Conservation of an Ancient Heritage. New York: Springer Publishing, 2018.

- Rioux, Nyle Lucien. “The Reign of ‘King Henequen’: The Rise and Fall of Yucatan’s Export Crop From the Pre-Columbian Era Through 1930.” BS thesis, Bates College, 2014.

- Villanueva-G, Rogel, David W. Roubik, and Wilberto Colli-Ucán. “Extinction of Melipona beecheii and Traditional Beekeeping in the Yucatán Peninsula.” Bee World 86, no. 2 (2005): 35–41.