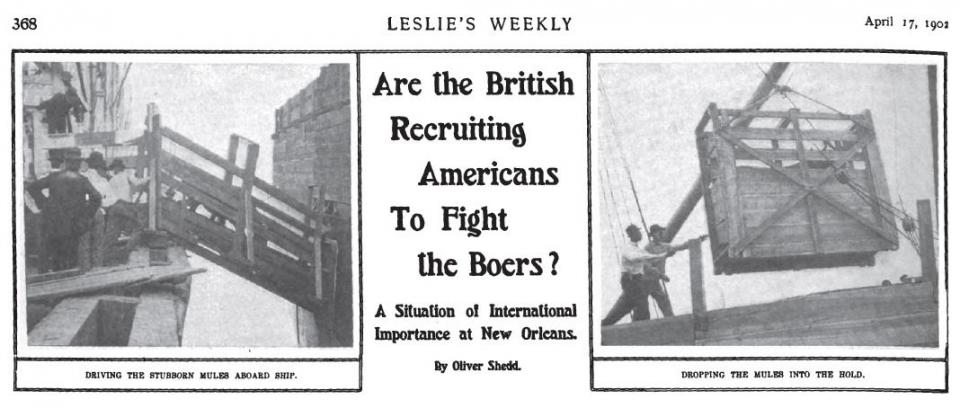

In the spring of 1902, American newspapers reported that Great Britain had established a military base in New Orleans, Louisiana, for the shipment of horses and mules from the United States to South Africa; they were to be remounts for the South African War, 1899–1902, the last fully horse-powered war in history. From the perspective of animal studies, while the horses and mules were not necessarily seen as mercenaries, they could be viewed as conscripted, foreign equine soldiers. With this in mind, when an article in an American news magazine asked in a headline, “Are the British Recruiting Americans to Fight the Boers?,” the answer had to be a resounding “Yes!”

Newspapers in 1902 reported that Great Britain had a military base in New Orleans, Louisiana, for the shipment of American horses and mules as remounts for the South African War, 1899–1902.

Newspapers in 1902 reported that Great Britain had a military base in New Orleans, Louisiana, for the shipment of American horses and mules as remounts for the South African War, 1899–1902.

Article by Oliver Shedd. “Are the British Recruiting Americans to Fight the Boers? A Situation of International Importance at New Orleans.” Leslie’s Weekly [1902]: 368. Photo courtesy of Library Company of Philadelphia via Google Books.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

According to Major-General Sir Frederick Smith, a leading military veterinary during the South African War, the conflict was most unique for its “loss of animal life.” In fact, the death of horses and mules in the South African War could be termed an equicide. Almost 60 percent of the horses and mules involved perished in what Smith called “a holocaust.” Upon arrival in South Africa their life expectancy was only six weeks. The Royal Commission on the War in South Africa concluded that “the chief cause of the loss of horses [and mules] in the War was that they were for the most part brought from distant countries, submitted to a long and deteriorating sea voyage, when landed sent into the field without time for recuperation, and there put to hard and continuous work on short rations.”

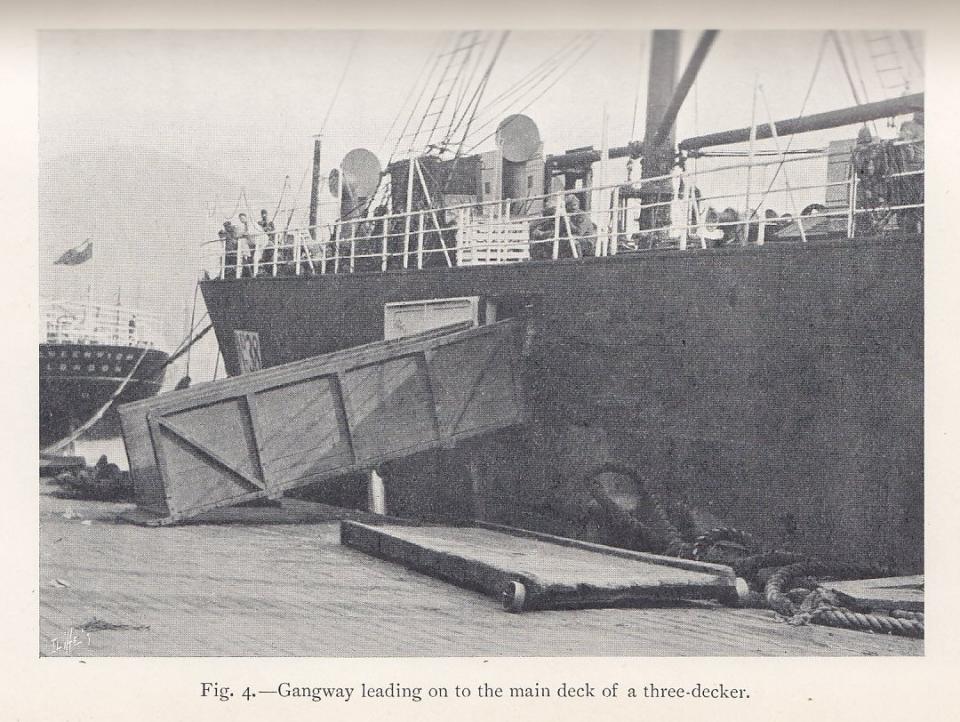

Horses and mules were forced with chains into gangways leading from the wharf to the side of the steamship.

Horses and mules were forced with chains into gangways leading from the wharf to the side of the steamship.

Photo by M. Horace Hayes. Horses on Board Ship [1902]. Photo courtesy of Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, TX, USA.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

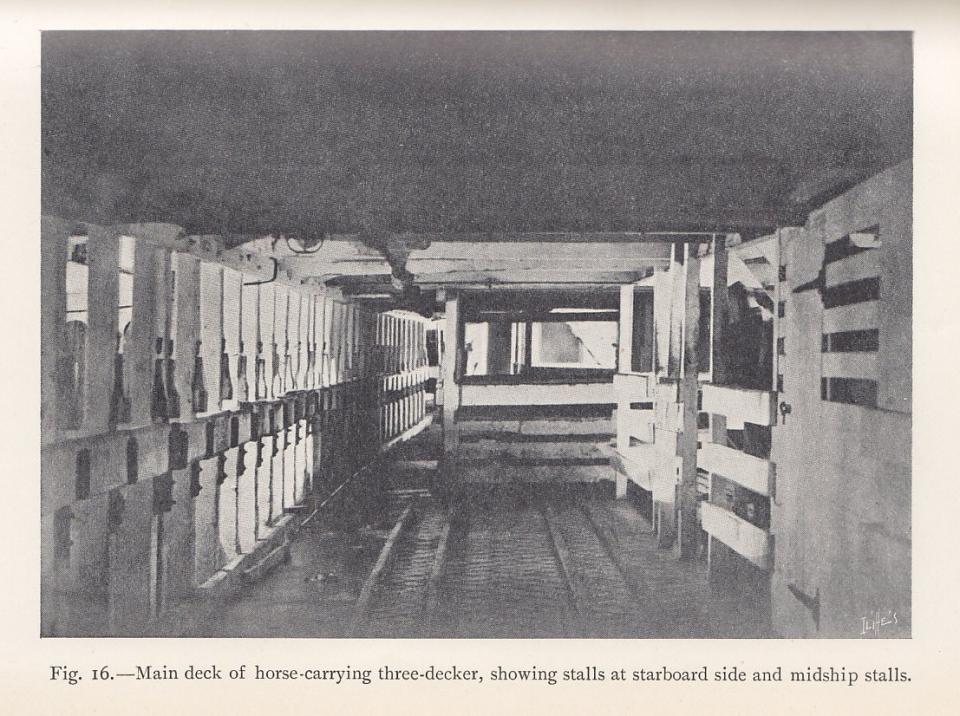

According to Frederick Smith, “The atmosphere below in which these animals lived was so foul, that the men employed looking after them would not work more than half-an-hour before coming on deck for air. The absolute blackness, excepting for a few electric lights, intensified the evil.”

According to Frederick Smith, “The atmosphere below in which these animals lived was so foul, that the men employed looking after them would not work more than half-an-hour before coming on deck for air. The absolute blackness, excepting for a few electric lights, intensified the evil.”

Photo by M. Horace Hayes. Horses on Board Ship [1902]. Photo courtesy of Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, TX, USA.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Most of the equines sent to South Africa came from the United States. From October 1899 to June 1902, 109,878 horses and 81,524 mules were shipped from New Orleans in 65 different British steamships making 166 voyages at an average cost of US$597,978 per month for each of the 32 months of the war. It was one of the largest global transports of animals in history.

In A Veterinary History of the War in South Africa, 1899–1902, Frederick Smith, British Army Veterinary Department officer during the South African War, described the horrible conditions for the mules on the SS Manchester City, which left New Orleans on 23 November and arrived in South Africa on 26 December 1899.

In A Veterinary History of the War in South Africa, 1899–1902, Frederick Smith, British Army Veterinary Department officer during the South African War, described the horrible conditions for the mules on the SS Manchester City, which left New Orleans on 23 November and arrived in South Africa on 26 December 1899.

Photo courtesy of RCVS Knowledge, London, UK.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Conditions on the steamers were terrible, paralleling those on the slave ships in the transatlantic slave trade. The irony should not be missed that some of the muleteers who were employed in New Orleans to take care of the horses and mules during their voyages through the Gulf of Mexico into the Caribbean Sea and across the Atlantic Ocean were African Americans. Horses and mules were packed into the steamships, stood up to their hocks in excrement, got sick with the pitch and roll of the ships, starved from insufficient fodder, and died and were thrown overboard. For example, the overcrowded SS Manchester City, which left New Orleans on 23 November 1899 with 2,090 mules, was a nightmare. In the tropics, temperatures between decks were often more than 46°C, and rarely below 37°C. According to Frederick Smith,

The atmosphere below in which these animals lived was so foul, that the men employed looking after them would not work more than half-an-hour before coming on deck for air. The absolute blackness, excepting for a few electric lights, intensified the evil. [In the Caribbean Sea] there was neither air nor water movement, so that even the dead animals thrown overboard had to be towed away. This created considerable delay in disposing of the dead still on the ship, which, in such a temperature rapidly became putrid, even their hoofs came off before they could be thrown overboard!

When the Manchester City arrived in South Africa after 36 days, 187 mules had died, an average of more than five per day.

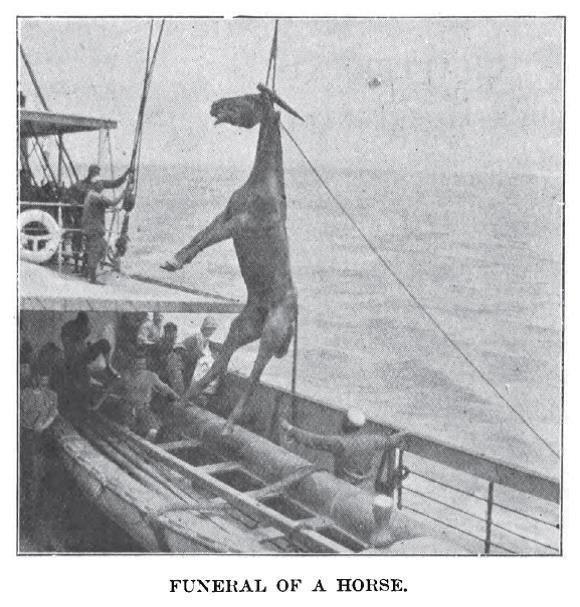

Horses and mules en route by steamship to South Africa for the South African War, 1899–1902, were thrown overboard into the Atlantic Ocean when they died of disease, starvation, or shipwreck.

Horses and mules en route by steamship to South Africa for the South African War, 1899–1902, were thrown overboard into the Atlantic Ocean when they died of disease, starvation, or shipwreck.

Photo by C. E. Forrest. “The Mounted Infantry Company from Aldershot to Pretoria.” The Oxfordshire Light Infantry in South Africa: A Narrative of the Boer War [1901]: 116. Photo courtesy of New York Public Library via Google Books.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Moreover, the suffering of the equines bound for South Africa was recorded in the eye-witness descriptions of their journeys. An article in the New Orleans Daily Picayune newspaper described the experience of the mules being loaded into the Manchester City:

The loading of this immense ship is done systematically and with the regularity of clockwork… . There are five closed gangways, three feet wide, leading from the wharf to the ship’s side, and as each mule is forced from the [train] car into this passage it is haltered with a strong leather halter, having a steel chain rein. Upon reaching the second deck of the ship, … the mules are blindfolded. They are then led some distance to the open hatchway, where is awaiting them an open, suspended cage. Not suspecting the instability of the cage, most of the animals are easily led into it, whereupon [the muleteers], stationed there for the purpose, close the doors, and signals are given for lowering … The blindfold is taken from the mules after they have been enticed into the lift cage. Many of them become very disturbed upon seeing the dark abyss into which they are being lowered, but they are helpless …

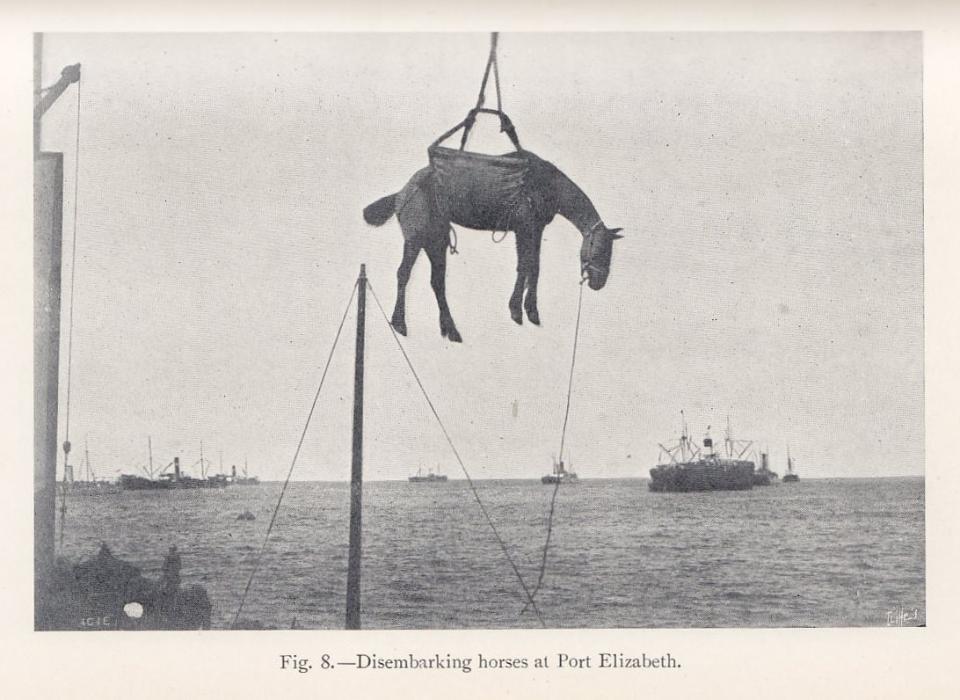

Steamships couldn’t dock at Port Elizabeth, so horses and mules were first slung onto smaller vessels there, then slung onto the pier, a terrifying experience for them.

Steamships couldn’t dock at Port Elizabeth, so horses and mules were first slung onto smaller vessels there, then slung onto the pier, a terrifying experience for them.

Photo by M. Horace Hayes. Horses on Board Ship [1902]. Photo courtesy of Bryan Wildenthal Memorial Library, Sul Ross State University, Alpine, TX, USA.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Without the American horses and mules sent from New Orleans to South Africa, the British Empire would not have won the South African War. The sickness, shipwrecks, and burials at sea endured by the animals, whom Frederick Smith called “this flotsam and jetsam of human passions and strife,” are worth remembering.

How to cite

Homan, Philip A. “American Horses for the South African War, 1899–1902.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2016), no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/7418.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2016 Philip A. Homan

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Hayes, M. Horace. Horses on Board Ship: A Guide to Their Management. London: Hurst and Blackett, 1902.

- Reynolds, Edward. Stand the Storm: A History of the Atlantic Slave Trade. London: Allison and Busby, 1985. Reprint, Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 1993.

- Smith, Frederick. Veterinary History of the War in South Africa, 1899–1902. London: H. & W. Brown, 1919.

- Wassermann, Johan. “A Tale of Two Port Cities: The Relationship between Durban and New Orleans during the Anglo-Boer War.” Historia 49, no. 1 (2004): 27–47.