Aims, Methods, and Mapping

Aims and Methods

In its various meanings “wilderness” is considered to be a place without a people, nature in the raw, quintessentially uncivilized. A wilderness may be void of roads and buildings, at once the embodiment of God and the inspiration for the human soul. Yet wilderness can also include traces of humanity or at least a distinct human presence in the ways that we describe it or circumscribe it. As we look for wilderness in other lands, we realize that wilderness—in form or function—can vary quite dramatically according to region or century or language.

Whether “wilderness” is conceived primarily as a dangerous mountain to be avoided, an immense tundra teeming with migratory birds or a tropical repository of biological and pharmaceutical wealth, depends on our heritage, and such heritage is intimately linked to the words we use to describe it. Adjectives in English such as “pristine,” “primitive,” “old-growth,” “untrammeled” describe wilderness but do not replace it. Wildlife dwells in this place, but sometimes so do wild, semi-human beings, at least in the places where they can be found. Trolls, leprechauns, satyrs, gnomes, and nymphs are all semi-humans nourished by the wild, and placed there by the imaginations of people who do not live in the wilderness.

It is precisely the linguistic differences in wilderness that concern us in this exhibition. The stunning cultural heritage of Europe and the world has produced an equally varied wilderness heritage. Because language manifests culture—indeed, some say language defines culture—a linguistic map is a good way to navigate global wilderness, and may do so more effectively than a political map. Indeed every language and dialect can reveal insights into the complexity of the meanings of wilderness. Noting how these meanings may overlap across language groups and nation-states provides further insight into understanding this term and the people who live there.

Our goal in this exhibit is to offer short descriptions of wilderness in a sampling of the world’s many languages, while providing sensory corroboration of what these various wildernesses actually look, feel, and sound like. Wilderness Babel is not centrally about the history of wilderness, for that is another and larger project, yet it is implicitly historical, as all words are. As a key concept and term, “wilderness” has changed its meanings over time, taking on different connotations according to period and event, and evolving according to usage and interest group. We hope that the project will be ongoing, with regular supplements in the form of new comments or the addition and updating of entries. Raymond Williams tells us that “nature” is one of the English language’s most complex words, so that translating the essence of this nature, namely “wilderness,” into other languages may keep us thinking and contributing for years to come.

What began as a somewhat Eurocentric project, aiming at encompassing Europe’s 23 official and 230 unofficial languages, can clearly be enriched by including descriptions of “wilderness” from the world’s other languages—although expanding beyond Europe pushes the number of languages to over 7,000, depending on how one defines language. And yet the question comes up time and again: what does wilderness mean in non-English speaking places and in languages other than English?

Mapping Wilderness, Mapping Languages

The main aim of maps is to show the spatial distribution of natural and cultural features, be they rivers and mountains or cities, political borders, oil spills, and even wilderness areas and language groups. It seems that any phenomenon can be mapped if it can be placed unequivocally in space. Cartography has obviously evolved beyond drawings on paper, and there are tools and methods that allow us to represent spatial features in more complicated ways, especially through the development of digital visualizations and geographic information systems (GIS) that track layers of features, as well as temporal changes of these features. Needless to say, the examples of maps offered here should be taken with several large grains of salt.

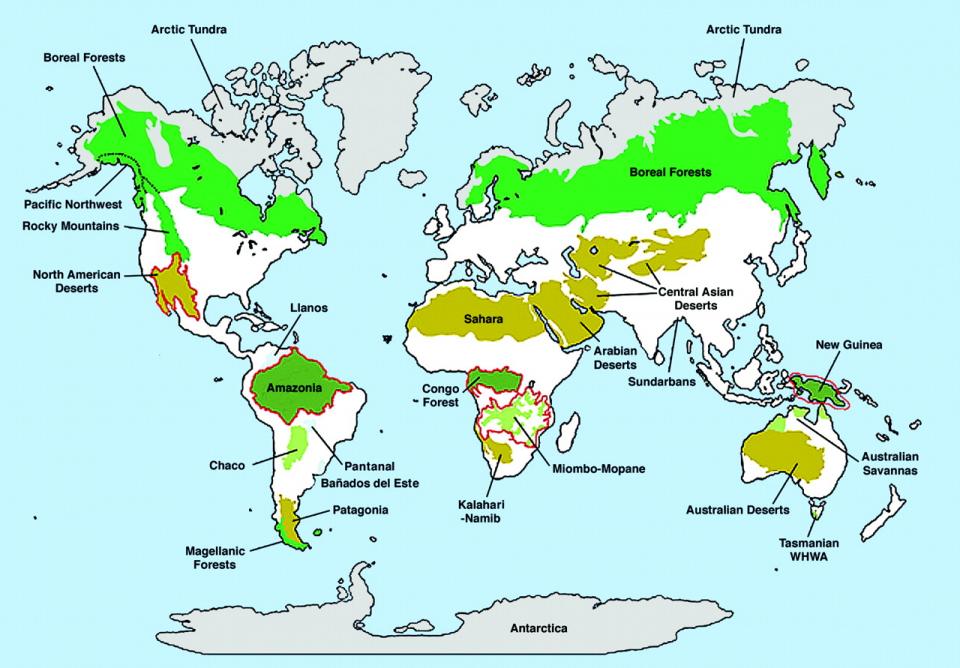

Overall map showing wilderness areas, human population density less than or equal to five people per km2, with biomes shaded, and the five high-biodiversity wilderness areas outlined in red.

Overall map showing wilderness areas, human population density less than or equal to five people per km2, with biomes shaded, and the five high-biodiversity wilderness areas outlined in red.

© 2003 National Academy of Sciences.

Map from Mittermeier, R. A. et al. “Wilderness and biodiversity conservation”, PNAS 2003;100:10309-10313.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

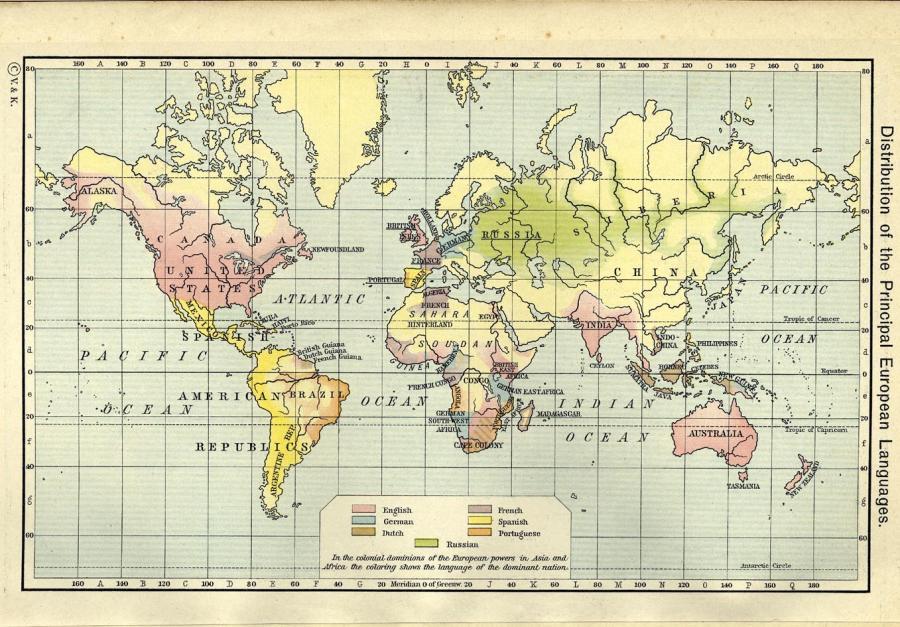

Shepherd’s map of the worldwide distribution of European languages in 1911.

Shepherd’s map of the worldwide distribution of European languages in 1911.

Map from Shepherd, William. Historical Atlas. New York: Henry Holt and Company, 1911.

Courtesy of University of Texas Library. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The mapping of both “wilderness” and “language” is a difficult task, since in both cases the feature being mapped has flexible and permeable boundaries; both depend enormously on precise definitions, and both display snapshots in time that do not reflect complexities of overlap and hybridity. Any graphic representation of wilderness and language will therefore be fraught with subjectivities. Therefore, in the exhibition navigation map we have decided to represent languages as points, instead of trying to draw their boundaries. Nonetheless, here we offer a few examples of such maps in order to show how others interpret and graph global wilderness and language, how such maps might generate new ideas about these phenomena, and how wilderness and language shed light on each other.

Global wilderness (in green).

Global wilderness (in green).

© 2018 United Nations Environment.

Dataset derived using the Digital Chart of the World 1993 version and methods based on the Australian National Wilderness Inventory in Lesslie, R. and Maslen, M. National Wilderness Inventory Handbook. 2nd edn., Australian Heritage Commission. Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, 1995.

Download the full dataset (for non-commercial purposes) in the form of an ESRI grid on the UNEP-WCMC website.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

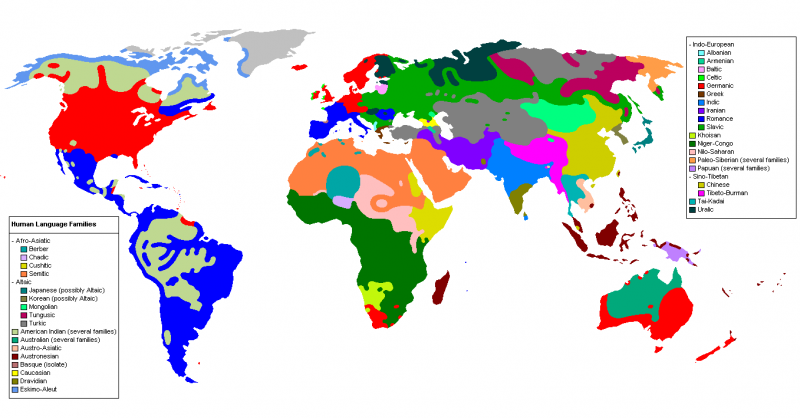

A cartographic approximation of the worldwide distribution of human language families.

A cartographic approximation of the worldwide distribution of human language families.

Graphic by Industrius, 2005.

Accessed via Wikimedia. Click here to view source.

A version of this map with language labels is also available here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In this regard we also suggest visiting the Last of the Wild project at Columbia University, the Endangered Languages website, and Steve Huffman’s language maps based on the World Language Mapping System.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter