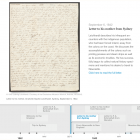

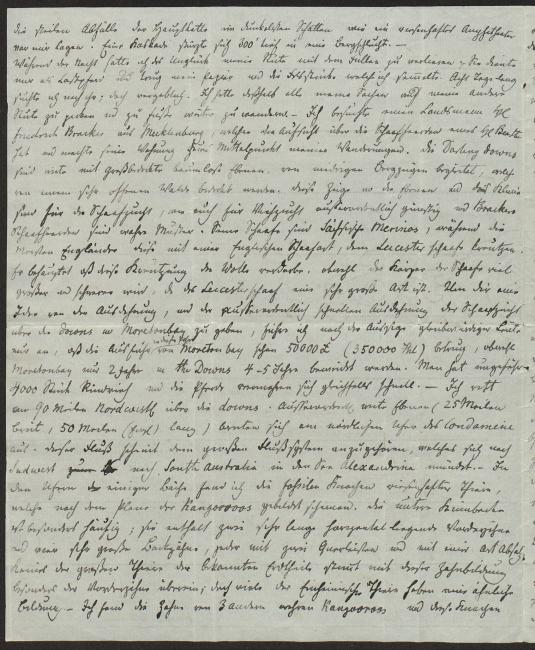

Letter to his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, Newcastle (14 May 1844)

Newcastle on the Hunter River, 14 May 1844

My dearest brother-in-law,

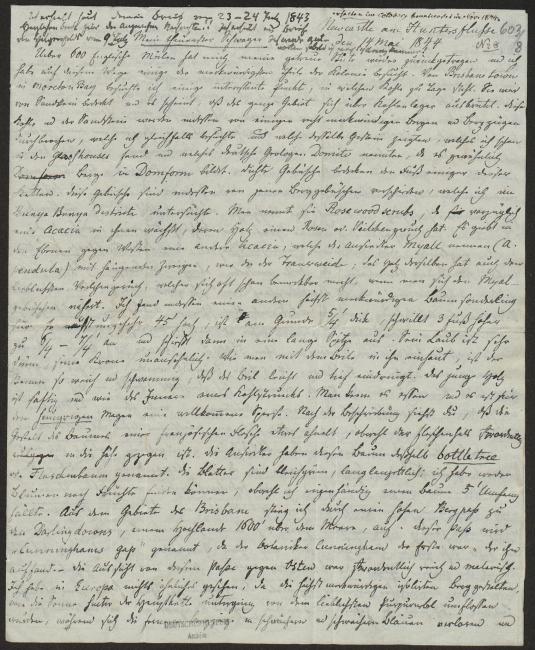

My trusted mare has carried me back for over 600 English miles and I toured some of the strangest parts of the colony on my way. From Brisbane town in Moreton Bay I went to see several interesting spots that hold visible coal depots. They are covered by sandstone rock and it appears that the entire area extends over coal depots. However, the coal and sandstone are broken in various places by several rather curious mountains and mountain ranges, which I also visited, and which contain the same rock that I had already found in the Glasshouses and which German geologists have named domite, since it usually forms mountains resembling domes. Thick shrubbery covers the foot of some of these ridges. These thickets differ from the mountain thickets that I examined in the Bunya Bunya district, however. They are called rosewood scrubs, since an acacia whose wood has a rose- or violet-like odor grows so well there. There is a different type of acacia in the westerly plains, which the settlers call “myall” (A. pendula), that has hanging branches like a weeping willow; its wood also emits the loveliest violet-like odor, which is frequently noticeable when one approaches the myall shrubs. I, however, discovered a different, rather peculiar type of tree here. It grows to a height of about 45’, is 5/4’ thick at its base, three feet up swells to a width of 6/4–7/4’, and then shoots up into an elongated tip. Its foliage is very light, its crown unsightly. When attacked with an axe, it turns out that its trunk is so soft and spongy that the axe easily and deeply penetrates it. The young wood is as juicy as a cabbage core. It is edible and makes for a complete meal for a hungry stomach. As you can tell from my description, the shape of the tree somewhat resembles a French bottle, although the bottleneck is extremely elongated. The settlers therefore named this tree bottle tree. Its leaves are pale green, long, and lanceolate. I have failed to find either flowers or fruits, although I myself cut down a tree that had a circumference of 5’. From the area of the Brisbane I climbed through a high mountain pass to the Darling Downs, a high plain 1600’ above sea level. This pass is called “Cunningham’s Gap,” since the botanist Cunningham was the first to discover it. — The view from this pass toward the east was extremely varied and picturesque. I never saw anything like it in Europe, with isolated mountains in remarkable formations bathed in the loveliest crimson fog as the sun was setting behind the main range, while the far-off mountain ranges were lost in fainter and

fainter hues of blue, and the steep slopes of the main range, hidden in darkest shadow, lay before me like a giant amphitheater. A cascade plummeted 300’ down into a glen. —

At night I had the misfortune to lose my mare with the foal. She had served me as a packhorse and carried my papers and the pieces of rock that I picked up. I searched for her for eight days, yet to no avail. I therefore had to load all my belongings onto my other mare and continue my travels on foot. — I went to visit a compatriot, Mr. Friedrich Bracker from Mecklenburg, who oversees the flocks of sheep of a Mr. Bolton, and I made his dwelling the center for my explorations. The Darling Downs are expansive, grass-covered, treeless plains, crisscrossed by rolling mountain ranges that are covered by a very open forest. The ridges, plains, and climate offer the most perfect conditions for sheep farming as well as livestock breeding, and Bracker’s flocks of sheep are true examples of their kind. His sheep are Saxon Merinos, whereas most Englishmen crossbred those with an English breed of sheep, the Leicester sheep. He claims that this crossbreed ruins the wool, although the body of the sheep much increases in height and weight since the Leicester sheep is a very large breed. To give you an idea of the extent of sheep farming across the Downs and Moreton Bay and the speed with which it has expanded, I will only say that, according to trustworthy sources, exports from Moreton Bay already totaled £50,000 (35,000 Thaler) this year, although Moreton Bay has only been used as pasture land for two years, and the Downs for only 4–5 years. There are about 4000 head of cattle, and horses breed just as rapidly. — I rode about 90 miles in a northwesterly direction across the Downs. Extremely expansive plains (25 miles wide, 50 miles (English) long) stretch along the northern bank of the Condamine. This river appears to belong to the large river system that flows southeast toward South Australia and empties into Lake Alexandria. — Along the banks of several streams I found fossilized bones of gigantic animals that appeared to have been built much like kangaroos. The lower mandible is especially common; it contains two very long, horizontally arranged front teeth and four very large molars, each with two transverse ridges and a kind of heel. None of the large animals of the known continents display this dentition, especially when it comes to the front teeth; yet many of the indigenous animals have similar formations. — I found the teeth of 3 other true kangaroos, and those bones

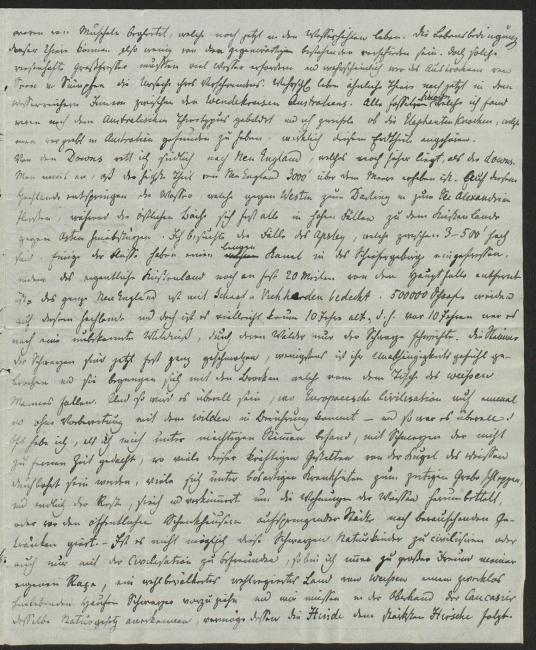

were accompanied by clamshells, like those that still live in the river caves. The living conditions of these animals could therefore not have differed too greatly from those prevailing today. Yet such gigantic herbivores must have required a lot of water, and most likely lakes and swamps drying out caused their extinction. Similar animals presumably still exist in the wet interior of Australia between the tropics. All of the fossilized bones that I found were formed in accordance with the Australian type of animal and I doubt whether the elephant bones which were said to have been discovered in Australia, truly belong to this continent.

From the Downs I rode southward to New England, which has an even higher elevation than the Downs. It is supposed that the highest part of New England has an elevation of 3000’ above sea level. This plateau harbors the sources of the waters that flow westward to the Darling and to Lake Alexandria, whereas the easterly streams plummet from high cascades toward the eastern coastal lands. I went to the falls of the Apsley, which are 3–500’ high. Some of the rivers have eaten a long channel through the shale mountain ranges, for the actual coastal lands are still almost 20 miles removed from the main cascades. All of New England is covered with flocks of sheep and herds of cattle. 50,000 sheep graze on this plateau, and yet it is perhaps not even 10 years old, that is, 10 years ago it was still an unknown wilderness through whose forests only the black man roamed. By now the clans of the blacks have almost completely melted away, at least their independent spirit has been broken and they content themselves with the morsels that fall off the white man’s table. And this is the way it will be wherever European civilization suddenly and without warning comes into contact with the savages—and this is how it was everywhere! It often pained me to think, when I found myself among mighty clans, of the not-so-distant future when many of these strong individuals will have been pierced by a white man’s bullet, many will have been dragged to an early grave by malicious illnesses, and finally the remaining ones, ailing and decrepit, will subsist as beggars near the houses of whites or lust after intoxicating beverages in front of the public inns of newly founded cities. If it is impossible to civilize these black children of nature or even to familiarize them with the basic tenets of civilization, then I am too much a friend of my own race and would prefer a well-populated, well-governed country of whites to a great aimless mass of blacks squandering their lives. In the predominance of Caucasians we see the same law of nature that determines that the doe will follow the strongest buck.

The inhabitants of New England live quite comfortably, whereas the settlers in the Downs and around the Moreton Bay District are still satisfied with the simplest wooden shacks. Many of the young men are beginning to marry, and womenfolk introduce a feeling of respectability, pursuit of domesticity and peaceful neighborly relations, and calm reasoning into the minds of many of these youngsters, who indulge in debauchery and drinking when they return to the coastal towns from the bush, much like sailors who return to port after a long journey at sea. An almost exclusively male population in an expanse of perhaps 600 miles is a highly interesting but not very satisfactory state of affairs. Nowhere else is it as evident why God carved Eve out of Adam’s rib. The laborers, shepherds, and herdsmen are still for the most part people who were sent here on account of their misdeeds and crimes but have since been granted their freedom. Few of them are married. They have no wife to feed, no children to provide for, no relatives to consider. They only live for themselves! And since they are neither given to serious thoughts about the future nor higher thoughts about the present, their energy is dedicated to pursuing immediate pleasure—whenever they can indulge in pleasures. As soon as they arrive at an inn they forget about their master, their work, even the very punishment they will incur for neglecting their duties; they regard the innkeeper as their father, his wife as their mother, those two are the only ones that welcome them with kindness and open arms. Thus they stay here until they have spent the last cent of their wages on drink, which fortunately does not take that long, and then they return to their duties to work yet again for another year, only to repeat the cycle.

From New England I went to Port Stephens, which belongs to the Agricultural Company, a company that obtained 2 million morgen of land on the condition that it would promote agriculture and cattle and sheep farming. At first it selected the land surrounding Port Stephens, so as to have access to a harbor, yet because it proved little suitable to sheep farming the government granted the company 1 million morgen of land in the interior, on the Peel, where there are excellent pasture lands. However, Port Stephens would be highly suitable for wine-growing, if only the company were to pay attention to this branch of cultivation. — It is for the best that you did not behold me in the flesh when I rode into Newcastle after having lived in the bush for so long. My trousers were so torn that a red woolen shirt which I was wearing as a frock hardly masked the trousers’ weak spots. People took me for a shepherd, a bushranger (robber) and so forth. — You can imagine how pleasant it felt to once again put on clean clothes. But I must end this letter now; I am healthy and hope that you are as well. Farewell and do not forget

your affectionate and loving brother-in-law and brother

[No signature.]

P.S.S. [bottom of last page:] Convey my greetings to dear mother and all the others.

[top of first page:] Today I received your letter of 23–24 July 1843. Thank you very much for the pleasant news!! I received a letter from the Hilgenfelds dated 9 July. I will answer as soon as I arrive in Sydney!!

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/8.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.