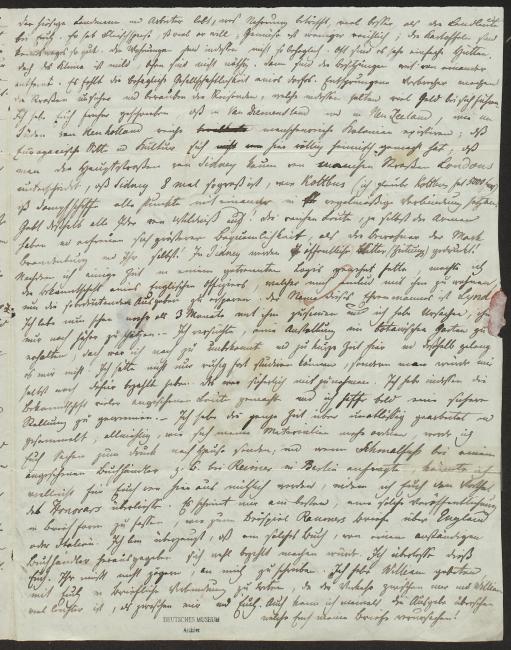

Letter to his mother, Charlotte Sophie Leichhardt, Sydney (6 September 1842)

Sydney, 6 September 1842

My dearest mother,

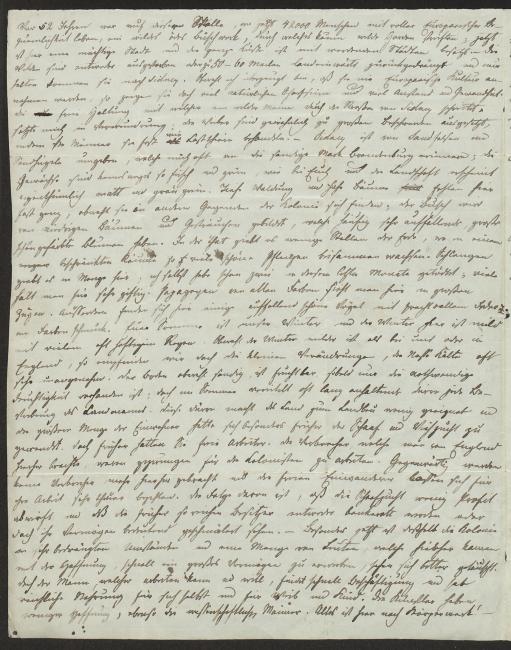

It has now been a year since I have received any message from you. I wrote letters to you from Paris, from England, and shortly after my arrival from Sydney, which you will surely have received. Every Sunday, when I quietly reminisce about the past, I find myself in your presence, I see you, I hear you and I share your thoughts; but then the whole globe once again moves between us; you return to the beloved homeland whereas I am left to my own devices in a foreign land, where I have to find solace, quietude, and fulfillment within myself. I am not feeling unhappy! For so long I have been accustomed to living amidst nature and finding joy in observing and studying it. The only pain that occasionally weighs heavy on my heart is solely the fact that I am wandering the earth far from you, that I cannot communicate with you more often, even if it is only in written form. I feel that you would want to see me, too; that you, my dearest mother, also yearn to hug your son to your heart as he wishes to hug you—and yet! And yet I cannot at present make any promises for the immanent fulfillment of our wishes. When I was still at home and because of my poverty could not dare to hope to achieve what I am accomplishing now, I believed that I could easily sacrifice everything to satisfy the urge to see the world. God in heaven fulfilled my secret wishes: I received what often the most affluent do not receive; everywhere I found support and was able to pursue my affinity for the study of nature without worries; yet another worry then took hold of me: I always received support but was never independent. William gave me money to go to New Netherland; after arriving here in Sydney I soon found good friends who took me in and saved me from incurring any costs in a very expensive place, in which I would have needed to pay more than 10 Rtl. per week for simple accommodations. I can live here, study here, but I cannot leave this place without finding someone who would take me with him. On the other hand I have made the acquaintance of respectable families; I have often felt favorably inclined toward girls, indeed, I have been deeply in love, yet my dependence has always prevented me from taking serious steps and making my feelings known. So you see that your son is ruled by manifold emotions, by early memories, by the always-burning love for his study of nature, by the impressions of the moment, which are likely to be the most dangerous for him und to prematurely anchor his wandering ship. Yet even if my mind is often restlessly moving, I can still assure you that I believe I have continually improved and that I still feel as innocent as I did the last time you held me in your arms. And for this I thank you! Because when I seek out the source of my moral principles, I arrive at the small chamber in our old house with its tiny window in which you taught us our morning and evening prayers and first introduced us to our heavenly Father.

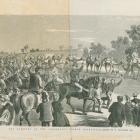

This spot—where 42,000 people now enjoy all the comforts of Europe—used to be wild, barren scrublands which fifty-two years ago even savage hordes seldom visited; now a mighty city stands here and the entire coast is dotted with cities being born. — The savages have either died out or been pushed back 50–60 miles into the interior and they only rarely come as far as Sydney. Although I am convinced that they will never adopt European culture, they nevertheless display much natural acumen and a lot of decorum and skillfulness. The poise with which a savage man strides through the streets of Sydney astonished me: the females usually are subject to much hardship since the men treat them almost like pack animals. — Sydney is surrounded by sandstone rock and sandy hills, which frequently remind me of the sandy Mark Brandenburg; the plants are not nearly as fresh and green as they are where you live and the landscape appears strangely dull and grayish-green. Dense woodlands and tall trees are almost completely absent here, although they exist in other parts of the colony; the bush is composed of low trees and shrubs which often sport very large, noticeable, beautifully colored flowers. There are indeed few places on earth where so many beautiful plants grow in such a small space. There are snakes in great quantities here; I have already killed two this past month myself; many are thought to be highly poisonous. One sees big flocks of parakeets in all colors here. In addition, a few remarkably beautiful birds with gorgeous coloring and plumage can be found. Your summer is our winter and winters here are mild with lots of heavy rains. Although winters are milder than at home or in England, we nevertheless frequently find the small changes, the damp cold, very unpleasant. The soil, although sandy, is fertile as soon as the required moisture is present; yet in summer long dry spells often thwarts the farmer’s every effort. This drought means that the land is ill-suited for farming and in the past in particular the greater part of the population turned to sheep and livestock breeding. Yet in the past they had access to free labor. The convicts who were transported here from England were forced to work for the colonists. At present, convicts are no longer brought here and free immigrants charge high fees for their labor services. As a consequence, sheep farming generates little profit and land owners who used to be very rich are either going bankrupt or are seeing their wealth diminish considerably. — The colony therefore finds itself in dire straits at present and a lot of people who came here in the hopes of quickly acquiring much wealth have been bitterly disappointed. Yet the man who is able and who wants to work quickly finds employment and can provide ample sustenance for himself and his wife and children. Artists have fewer prospects, as do men of science. Everything here revolves around physical labor!

As far as nourishment is concerned, the local farmer or worker is better off than a farmer at home. He can eat as much meat as he desires, vegetables are less abundant; potatoes are not nearly as good. Living quarters are, however, not so comfortable. Frequently they are but simple huts. Yet the climate is mild. Stoves are not necessary. But then, settlements are far apart. The easy sociability of a village is absent. Escaped convicts roam the streets and rob travelers, who, for this reason rarely carry large amounts of money. I wrote you earlier that rich and richly populated colonies exist in Van Diemen’s Land and in New Zealand as they do in the south of New Holland; that European customs and culture are fully at home here; that Sydney’s main streets are barely distinguishable from some streets in London; that Sydney is 8 times the size of Cottbus (I believe that Cottbus has a population of 5000); that steamships provide regular connections between all places. Abandon therefore all notions of a wilderness! The rich, and even the poor, live in and enjoy greater levels of comfort than the inhabitants of the Mark Brandenburg and you yourselves! In Sydney, public broadsheets (newspapers) are being printed! After I had resided in my detached quarters for a while, I made the acquaintance of an English officer, who invited me to stay with him to save on the very high rent. This gentleman’s name is Lynd. By now, I have already lived with him for more than three months and have good reasons to value him even more highly. — I tried to secure employment with the botanical gardens, yet I did not succeed because I was still too much of an unknown and had been here for too short a time. I could have not only continued my studies in peace, but they would even have paid me for doing so. This would have been too good an opportunity to pass up. Meanwhile, I have made the acquaintance of many highly-respected people and hope to soon secure a permanent position. — I have been tirelessly working collecting this whole time; gradually, as my materials become more organized, I will send you things to publish at home; and if Schmalfuß were to make inquiries at a reputable booksellers, for example Reimer in Berlin, I could perhaps be of use to you by ceding you the honorarium. It appears best to me to present such a publication in the form of letters, such as Raumer’s letters on England or Italy, for example. I am convinced that such a book, if published by a reputable bookseller, would indeed pay for itself. I leave this up to you. Do not hesitate to write me. I have asked William to get in touch with you by letter since communication between myself and William is much easier than it is between me and you. In addition, I could never ignore the expense that my letters create for you!

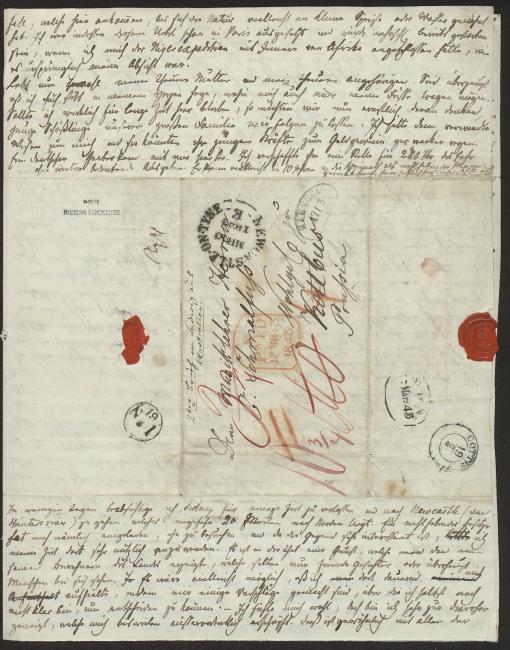

In a few days I intend to leave Sydney for a while and to go to Newcastle (on the Hunter River), which is situated about 20 miles north of here. Specifically, a prosperous landowner has invited me to visit him and since the area is very interesting I hope to fruitfully occupy my time there. It is indeed doing a favor to country’s isolated inhabitants, who rarely get to see strange faces or even people at all. It is possible that I might stay there permanently, for I have received a few offers which I have not yet considered enough to make a decision. — I am feeling well; yet I am very inclined toward diarrhea, which on occasion extraordinarily exhausts me. This generally happens to everyone who arrives here until one’s constitution has become acclimated to the climate, or perhaps the food, or the water. I was already subjected to this malady in Paris and would probably be dead by now if I had joined the Niger expedition into the heart of Africa, as I had originally planned.

Farewell my dear mother and my dear relatives. Be assured that I always carry you in my heart wherever my feet may carry me. Should I actually remain here for a very long time we might think about having young members of our extended family join me. I would then be surrounded by relatives and they could heartily dedicate the strength of youth to making money. A German tanner came here with me. I found him a position that pays 280 Thaler a year with few substantial expenses. After perhaps 10 years he can return home a prosperous man.

Most affectionately,

Your loving Brother-in-Law and Son

Ludwig

Used by permission of the Deutsches Museum, Munich, Archives, HS 603/2.

English translation by Nadine Zimmerli.