Natural Resources

Highlights of this chapter

Slideshow of pre-pipeline Alaskan wilderness

This chapter features a slideshow of photographs taken by Dennis Cowals for the Documerica Project (1971–77). In August 1973 and 1974, Cowals documented the Alaskan wilderness from Prudhoe Bay south to Valdez, which would later become the site of the Trans-Alaskan Pipeline.

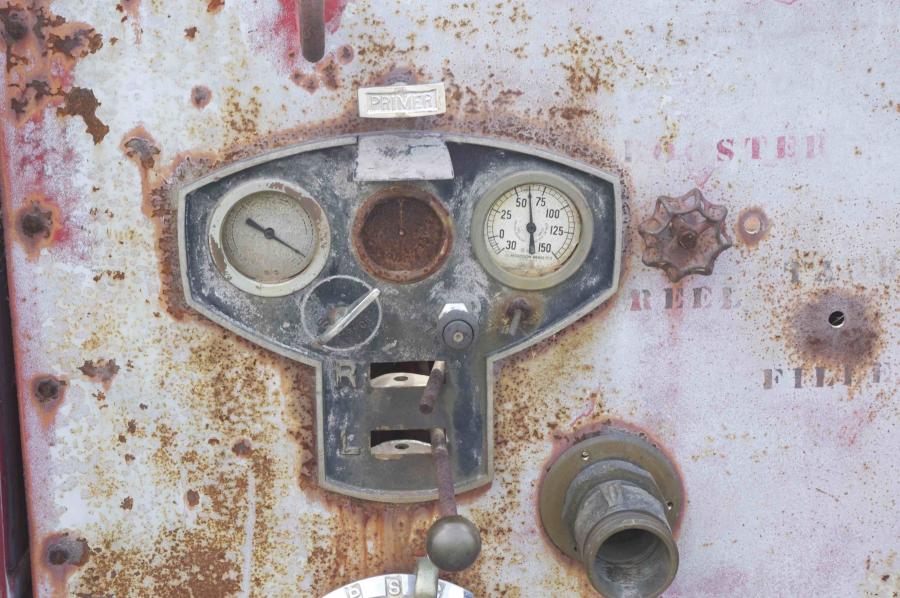

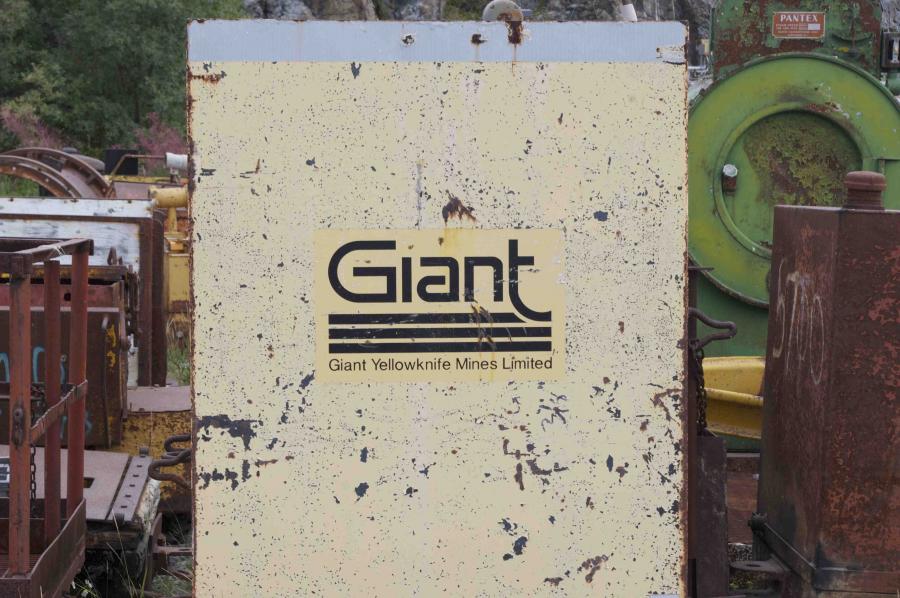

Slideshow of the Giant Mine

The Giant Mine, a gold mine located outside Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, closed in 2005. Since then, attention has focused on containing its waste and remediating its environmental impact.

Animation of an indigenous poem

This short video animates the Inuit poem “I Am But a Little Woman,” first written down in 1927. The poem evokes the beauty and power of nature, as well as the bond between mother and daughter. Video by Gyu Oh, 2010.

Exploitation of Resources, and Environmental Hazards

Mining and Offshore Exploitation

Nunavut: Our Land

Mary River Project

Conclusion

Exploitation of Resources, and Environmental Hazards

As gas, oil, and military development spread throughout the Arctic, infrastructures such as roads, pipelines, airstrips, and ports have disrupted and fragmented the habitat.

For millennia, the peoples inhabiting the Arctic region have lived on the resources of land and sea through hunting, fishing, and herding. Human impact and environmental transformation intensified with the beginning of the fur trade, followed by settlement by non-indigenous people, the Gold Rush, exploitation of minerals and fossil fuels, and finally the construction of military infrastructure during the Cold War. These activities encroached on traditional indigenous ways of life and the balance between humankind and the environment. Understanding the sustainability and impact of resource exploitation on these fragile ecosystems requires tracing this history. The Native peoples have long been involved in struggles to mitigate the effects of industrial development of their land, but also in trying to control these changes as well as benefit from them. As the extraction of resources intensifies around the Arctic, more infrastructure and industrial enterprises are being set up in the region.

As gas, oil, and military development spread throughout the Arctic, infrastructures such as roads, pipelines, airstrips, and ports have disrupted and fragmented the habitat. While less than five percent of the Arctic was affected by infrastructure development between 1900 and 1950, transport is considered crucial to the exploitation of the area today.

Giant gold mine (1)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (2)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (3)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (4)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (5)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (6)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (7)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (8)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (9)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (10)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (11)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (12)

© Enrico Mariotti.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (13)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (14)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (15)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (16)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Giant gold mine (17)

Photo by Enrico Mariotti, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

No. 40. Pictures of the Giant Mine, a gold mine located outside Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. Located along the Great Slave Lake’s beautiful Back Bay and along what is now the historic Ingraham Trail, it was one of the richest gold mines ever found in Canada. Gold was discovered in 1935, leading to the production of seven million ounces and resulting in one of the longest continuous gold mining operations in Canadian mining history. Ore processing at Giant Mine ceased after 1999, and in 2005 Giant Mine officially became an abandoned mine site. When the mine closed, attention focused on the environmental issues left behind, notably 237,000 tonnes of arsenic trioxide stored in underground chambers. For this reason the Canadian government started the Giant Mine Remediation Project, designed to protect the environment and human health and safety by means of long-term containment and management of arsenic trioxide waste, water treatment, and surface clean-up of the site. Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. August 2013. Photos taken by Enrico Mariotti. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

After World War II, North America experienced economic growth stimulated by consumer demand and supported by government policies. The need to provide power for economic expansion and modernization plans led Canada and the United States to develop more efficient infrastructure networks and identify new sources of energy. Between 1946 and 1961, energy derived from gas and oil increased to account for over 80 percent of total consumption. Pipelines and high-voltage transmission lines brought cheap energy from the North to consumer markets in the South, and radically transformed the environments of Canada and the United States as well as people’s attitudes and socioeconomic behaviors. Optimism and faith in progress experienced a setback in the 1960s with economic problems, political turmoil (connected with opposition to the role of the USA in Vietnam) and the growth of a new movement against standardization and for individual freedom (counterculture, left wing and peace movements, etc.). Strategies for developing the North have sometimes been bound up with political ambition: in 1958, for example, the Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker presented the construction of roads in the North as a central part of his vision for the country’s future during his re-election campaign.

Diefenbaker drew inspiration from the achievements of John A. Macdonald, Canada’s first Prime Minister, in opening up Canada’s West by promising to allow vast new areas for oil and mineral exploration. Diefenbaker invested millions of dollars in a northern infrastructure program known as “Roads to Resources.” While this led to the construction of over 2,000 kilometers of roads across the northern territories, it eventually proved too difficult to build roads above the tree line, including one along the Mackenzie Valley intended to connect the Northwest Passage corridor to the southern market.

On 12 March 1968 the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) and Exxon discovered North America’s largest oil field in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. This find awakened hopes of solving North America’s energy supply problems through large-scale exploitation of the northern territory.

It was, however, the events of 1968 that radically changed any plans for progress involving the northern part of the American continent. On 12 March 1968 the Atlantic Richfield Company (ARCO) and Exxon discovered North America’s largest oil field in Prudhoe Bay, Alaska. This find awakened hopes of solving North America’s energy supply problems through large-scale exploitation of the northern territory. In the meantime, a heated debate about the delivery system took place in the media and agitated public opinion both in Canada and in the US.

The relationship between the exploitation of resources and territorial sovereignty was also blown up in Alaska, which has long been a battleground between development interests and environmentalists, especially after Congress made Alaska a state in 1959. The new state and the Native tribes discussed the selection of lands for acquisition for the next twenty years, and in 1966 the Secretary of the Interior Stewart Udall halted all applications for the use of free land in Alaska until Congress had reached a decision on Native claims. The Prudhoe Bay discovery, however, made everything much more complicated.

The controversy over oil drilling and transportation divided public opinion into two different camps: those who wanted to explore for oil and gas, and those who wanted to keep the area off-limits to all development. For advocates of the wilderness, compromise was unthinkable: any development in a pristine area constituted an unacceptable violation. For those advocating development, this attitude reflected a lack of concern for the area’s economic needs.

The extraction and transportation of Arctic resources brings with it various difficulties and high costs; it also affects the northern mythology embedded in the minds of many Canadians. Together with this political situation, the discovery of oil on Alaska’s North Slope in 1968 triggered a combination of competing interests and forces that changed the history of the Arctic and increased Canadian anxieties. Canadian sovereignty in the Arctic was challenged by development in the region and especially investigations as to the most economical means of transporting oil southwards. The press reported that maps had been issued by United States oil companies showing the islands of the North Archipelago as disputed territories. There were also apparently groundless rumors that the US government had questioned Canada’s right to lease areas in the Canadian Arctic for exploration purposes.

On 10 February 1969, the three major US and British oil companies (Humble, Atlantic Richfield, and BP) that had been developing oil reserves on Alaska’s North Slope joined forces in a loose consortium called the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS), announcing plans to build a 798-mile pipeline from the oil fields at Prudhoe Bay to the port of Valdez. The announcement resulted in a surge of national environmental sentiment.

The opponents used technicalities, legal quibbles, Native rights and land claims in an attempt to delay the project, and whipped up public opinion over the oil industry’s destructive practices in the Arctic. In 1969 the former governor of Alaska, Walter Hickel, was appointed by President Nixon to head the Department of the Interior, where he was able to push for his Trans-Alaskan Pipeline project.

Pictures taken by Dennis Cowals for the Documerica Project (1971-1977). During August 1973 and August 1974, Cowals documented sites of the future Alaskan Pipeline in their pre-pipeline Alaska wilderness from Prudhoe Bay south to Valdez, the terminus of the pipeline. Documerica was a project sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that hired freelance photographers to capture images relating to environmental problems, EPA activities, and everyday life in the 1970s. Dennis Cowals - National Archives and Records Administration

Alaska Pipeline (2)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (3)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (4)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (5)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (6)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (7)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (8)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (9)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (10)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (11)

Dennis Cowals Documerica Project

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (12)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (13)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (14)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (15)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Alaska Pipeline (16)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

No. 41. Pictures taken by Dennis Cowals for the Documerica Project (1971–77). In August 1973 and 1974, Cowals documented sites of the future Alaskan pipeline in the pre-pipeline Alaskan wilderness from Prudhoe Bay south to Valdez, the pipeline’s terminus. Documerica was a project sponsored by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) that hired freelance photographers to capture images relating to environmental problems, EPA activities, and everyday life in the 1970s. Dennis Cowals—National Archives and Records Administration, no known copyright restrictions.

The Native claims seemed to reach a solution in December 1971, when the US Congress passed the Alaska Native Claims Settlement Act granting the Natives 44 million acres and one billion dollars payable in oil royalties. While this decision gave the Natives great financial power, the act denied any claims to the corridor earmarked for an oil pipeline so as to ensure that property rights could not be used to block the project.

In Canada the possibilities for new investigations included two different areas—namely, the Mackenzie Delta and the High Arctic Island—where large deposits of natural gas and a moderate amount of commercial oil were found. In the ensuing excitement, and considering also the international implications, the government under Pierre Elliott Trudeau took an interest in the economic exploitation of the North and provided funds for petroleum exploration, also coming to regard oil companies as instruments of foreign policy to solidify Canada’s hold on the North.

To further Canadian-based exploration efforts in the Arctic, Panarctic Oils was founded as a consortium of companies with the government as a major shareholder. Panarctic made a significant discovery of gas at Drake Point on Melville Island in 1969. As exploration proceeded in the upper Arctic, attention also focused on the Mackenzie Delta. The first successful onshore oil strikes were at Atkinson Point on the Tuktoyaktuk Peninsula in 1969 and at Parson’s Lake in 1970.

The new resources brought to the surface the problem of distribution: How were the oil and gas to get from the Arctic Archipelago to the southern markets? One of the major projects presented was the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, a proposed corridor to transport natural gas from the Beaufort Sea through Canada’s Northwest Territories to connect with gas pipelines in northern Alberta. The project aroused great concern and was ultimately scrapped in the wake of an inquiry conducted by Justice Thomas Berger. When the pipeline proposal emerged, it acted as a catalyst for the feelings of frustration and concern of the northern Native communities. Land claims become the means of opposing and trying to reverse the social and cultural erosion to which they were being subjected in the name of development.

Northern exploration increased after the oil crisis of the early 1970s. The oil shortage stimulated general public awareness of just how precarious previously reliable sources of hydrocarbons actually were. By that time, production within the US, even including the large contribution from Prudhoe Bay, could no longer meet internal needs, and dependence on imported supplies grew as a result. In view of this, activities in the Beaufort Sea and Mackenzie Delta area were stepped up with the drilling of many onshore and offshore wells. Pending the findings of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline Inquiry, fleets of reinforced drill ships were used to withstand the rigors of deep water in the Beaufort Sea. The first Beaufort Sea wells were drilled from manmade islands of silt developed by Dome Petroleum and Gulf. Political maneuvers and lobbying, aimed at securing economic and political interests, led to public frustration.

Credit: Riccardo Pravettoni, UNEP/GRID-Arendal.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

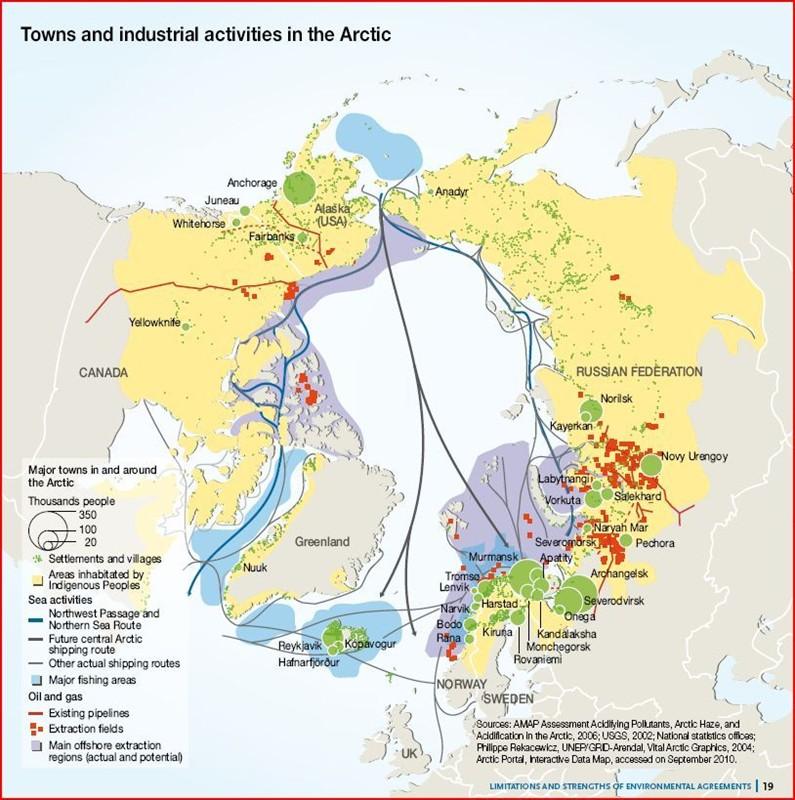

No. 42. Towns and industrial activities in the Arctic. The Arctic is home to approximately four million people, with the share of indigenous and non-indigenous populations varying widely between the Arctic states. Larger settlements are usually located in resource-strategic positions. Rich deposits of natural resources are spurring industrial activity in the region. The Russian Arctic, for example, has only 1.5% of the country’s population, but accounts for 11 percent of its gross domestic product and 22 percent of its exports. The Arctic could also hold up to 22 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil and natural gas reserves. Commercial shipping across the Arctic along the Northeast Passage and Northern Sea Route is expected to increase dramatically over the next few decades with retreating ice conditions. Source: Riccardo Pravettoni, UNEP/GRID-Arendal, 2010.

As a result, opposition groups arose in Canada, inspired by the US civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s. The environmental justice movements embodied some of the principles of social and ecological citizenship. These campaigns make it clear how the poor, and often certain ethnic groups, suffer disproportionately from environmental harm.

Some Canadian politicians underlined public concern for the wilderness as a basic component of Canadian identity. Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau went so far as to claim that Canada could become the world leader in the protection of air, water, and living resources.

Some Canadian politicians underlined public concern for the wilderness as a basic component of Canadian identity. Prime Minister Pierre Elliott Trudeau went so far as to claim that Canada could become the world leader in the protection of air, water, and living resources. The broad shape of Canada’s environmental institutions was established in the early 1970s with the creation of Canada’s first environment ministries at the federal and provincial levels. In the meantime, other movements and individuals focused specifically on the problems of the northern environment and responded to the 1971 government statement on the Mackenzie Valley Oil Pipeline. The significance of the modern environmental movement lies in the changing definition of citizenship in relation to an increasingly powerful state. The “green revolution” at the national level was built upon the “rights revolution” that preceded and accompanied it. It goes further than existing conceptions of social citizenship in seeking to include human “non-citizens” (i.e., non-citizen residents of a territory, residents of other territories, and future generations) in the decision-making process, as well as recognizing the supranational nature of environmental concerns and questions of global justice.

There have been many examples of how indigenous peoples, as nations, communities, and governments, have diverse and sometimes contradictory collective interests in the environment that differ from those of non-Native or mainstream environmentalists.

Although the indigenous experience of the environmental movement is connected with other movements, the Native peoples’ battle remains a challenge to the whole of society, as they are fighting for the survival of their nations and ways of life. There have been many examples of how indigenous peoples, as nations, communities, and governments, have diverse and sometimes contradictory collective interests in the environment that differ from those of non-Native or mainstream environmentalists. Their distinct interests stem primarily from the central role of the environment within their cultures and the economic importance of subsistence activities in their communities. The material reality of their cultures, spiritualities, and livelihoods is based on keeping the environment healthy for future generations. For this reason, they mobilize as an autonomous cultural bloc in opposition to the dominant system with the aim of creating space outside capitalist society for the liberation of indigenous nations and nature. These basic elements account for the Native peoples’ interest in resisting development and their concurrent interest in participating in the development of resources in the hope of improving the health and well-being of the communities. These dual and contradictory aims explain the Native approach to the policies of northern development and their difficult relations with the south.

The polar regions have long provided key ecosystem services, particularly where biodiversity and the harvesting of resources are concentrated. However, the sensitivity of these ecosystems to disturbances caused by resource extraction makes them extremely vulnerable. In the last 20 years, climate change has substantially affected ecosystem services and human well-being. Today, rising temperatures are also having a major effect on human services, including subsistence resources and support for industrial infrastructure. Important changes include the increased dominance of shrubs in the Arctic wetlands, which contributes to summer warming trends and alters the forage available to caribou; changes in insect populations that alter the food sources available to birds; and a rapid increase in the prevalence and impact of invasive alien species, such as moose and the grizzly bear, which have moved northwards in response to warming.

Climate change will also have a major impact on human projects through the thawing of permafrost, rapid melting of ice cover, and increasing precipitation levels. Rising temperatures are affecting one of the most important routes of transportation in the permafrost areas of North America, namely temporary winter ice roads that cross frozen lakes, rivers, and tundra.

In the Northwest Passage, warming has reduced access to marine mammals, as a result of the decrease in sea ice, and made the physical and biotic environment less predictable. At the same time, however, it has increased shipping. Reductions in the extent of sea ice in the summer months will increase access along sea routes, thus fostering northern development, and together with the rising sea levels it will hasten the coastal erosion currently threatening many villages. Climate change will also have a major impact on human projects through the thawing of permafrost, rapid melting of ice cover, and increasing precipitation levels.

Rising temperatures are affecting one of the most important routes of transportation in the permafrost areas of North America, namely temporary winter ice roads that cross frozen lakes, rivers, and tundra. These corridors have played an increasingly important role for community supply and industrial development because of their practical advantages, such as low costs and minimal environmental impact. The construction of these roads depends each year on the structural stability of the frozen base material, and recent data show a reduction in the duration of the opening and closing dates for tundra travel on the North Slope of Alaska and in the Canadian Arctic.

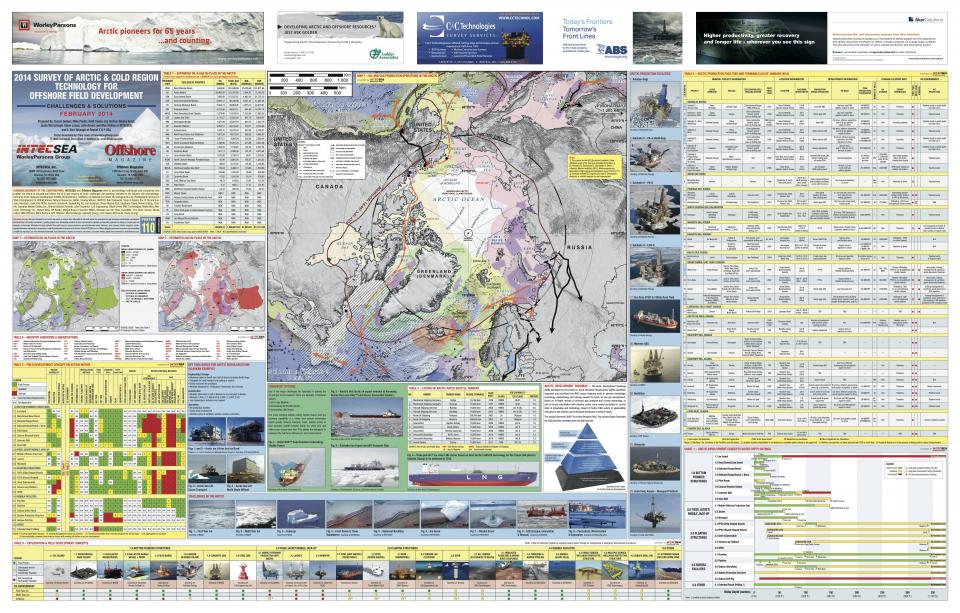

No. 43. 2014 survey of Arctic & Cold Region Technology for Offshore Field Development. Source: INTECSEA and Offshore Magazine.

Mining and Offshore Exploitation

According to estimates of the US Geological Survey, about 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil, 30 percent of its undiscovered natural gas, and 20 percent of its undiscovered natural gas liquids lie beneath the Arctic ice.

According to estimates of the US Geological Survey, about 13 percent of the world’s undiscovered oil, 30 percent of its undiscovered natural gas, and 20 percent of its undiscovered natural gas liquids lie beneath the Arctic ice.

As outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, a country can legally extend its rights over oil and gas deposits to the edge of its continental shelf, even if this stretches beyond the 200-mile exclusive economic zone. It is necessary to develop infrastructure in order to exploit this undiscovered treasure. Russia has made this one of its highest national priorities and has consequently built up the world’s largest fleet of icebreakers and invested more in Arctic infrastructure than any other country. Russia is also building deepwater ports and rail terminals to service the Northern Sea Route, while the USA and Canada have thus far only floated proposals for similar kinds of infrastructure for the Northwest Passage. There are also problems, however, such as drilling setbacks and an uncertain regulatory environment, which have led in the past to the withdrawal from Alaska of three major oil companies, ConocoPhillips, Royal Dutch Shell, and Statoil. Even with adequate infrastructure in place, however, the Arctic will be a difficult place to operate in. The cost of entry, including insurance and fuel consumption, is extremely high: floating pieces of ice can damage hulls, and it is extremely dangerous to pass through in a ship not designed, and a crew not trained for these conditions, because there are no repair services for much of the route and the cost of repair in Canada or the USA would consume the profits from the trip.

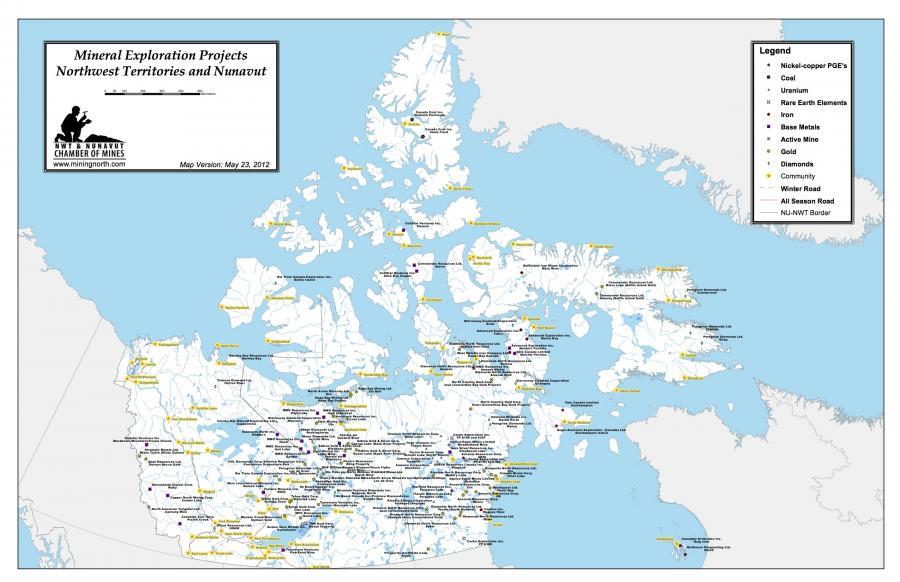

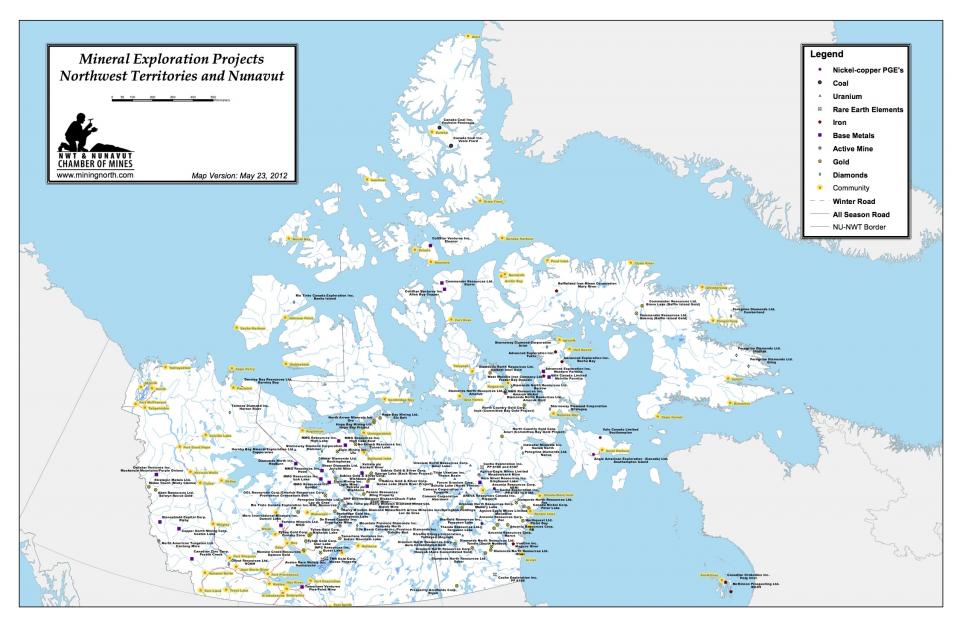

No. 44. Northwest Territories and Nunavut Active Mineral Exploration Projects for the year 2012.

No. 44. Northwest Territories and Nunavut Active Mineral Exploration Projects for the year 2012.

Source: NWT & Nunavut Chamber of Mines. “Active Mineral Exploration Projects 2012.” NWT & Nunavut - Chamber of Mines. In www.miningnorth.com

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

No. 44. Northwest Territories and Nunavut Active Mineral Exploration Projects, 2012. Source: NWT & Nunavut. “Active Mineral Exploration Projects 2012.” NWT & Nunavut—Chamber of Mines. In www.miningnorth.com.

The Arctic is also currently a destination for supplies needed by drilling and mining ventures and small local communities, as well as a loading point for raw materials headed for the world market. This means traveling with cargo equipment such as graders for roads, camp facilities, cranes, bulldozers, trucks, and explosives. Once the mine is up and running, it is necessary to resupply it using cargo with raw materials from the mine. Because air transport remains too expensive for mineral cargo, and road and pipeline routes are complicated in areas of permafrost, frozen ground, and fragile ecosystems, Arctic shipping is growing. New icebreakers are improving in efficiency, and climate change means that ice-free navigation seasons will likely be extended.

This scenario raises important questions about how development can be sustainable and how it might directly benefit Inuit communities, taking into account the high costs, uncertainty over rights to the land, and sometimes reduced estimates of reserves that can cause the delay and even the abandonment of mining projects.

After the Deepwater Horizon blowout disaster in the Gulf of Mexico, the Canadian National Energy Board—the federal body responsible for regulating offshore drilling in the Canadian Arctic—announced a strict procedure for reviewing drilling proposals. Even if there are no companies actively drilling, or applying to drill, in Canada’s Arctic waters, Shell, BP, ExxonMobil, and Imperial Oil all hold exploration licenses in the region.

The primary consideration is that an oil spill similar to that of the Deepwater Horizon case would have devastating consequences in the Arctic, as both the Canadian and US coastguard have indicated that they lack the technology, equipment, workforce, and vessels to cope with a major spill in the Arctic once sea ice has formed in the winter.

In December 2016, Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and US President Barack Obama conjointly signed an act to ban offshore oil and gas activity for 5 years. On 28 April 2017 the newly elected US President Donald Trump signed an executive order to implement an “America-First Offshore Energy Strategy.” Trump’s executive order could rescind Obama’s withdrawal of Arctic and Atlantic waters, and it instructs the US Department of Interior to review the various ways it could take down barriers to drilling.

Nunavut: Our Land

Even if their levels of comfort and wellness have increased, today the connection between Inuit and the land has weakened.

The survival of Inuit once depended on the land. They have both a physical and a spiritual relationship with the environment, and this relationship is embodied in their traditional practices of hunting and seasonal migration. Inuit lived as nomads, moving from place to place in order to follow the migration routes of caribou, seals, fish, and birds. In Inuit society, animals hold the central role; not only do they share the land on which the Inuit live and serve as the traditional food source, but they are also present in every part of Inuit culture, religion, and art. Their culture is deeply connected to the vast land they inhabit: for thousands of years, Inuit observed the climate, landscapes, and seas. Thanks to their knowledge of the land and its life forms, they developed the skills they needed to adapt and survive. Inuit have always assisted one another and helped when food was scarce. It was through this connection to land, wildlife, and to each other that they survived for centuries. Because each region has its own distinct ecosystem, Inuit faced different hunting challenges in every area in which they lived. Inuit diet includes animals from various habitats, such as caribou, seals, Arctic char, walruses, and whales.

No. 45. Nunavut Animation Lab: I Am But a Little Woman. Inspired by an Inuit poem first written down in 1927, this animated short evokes the beauty and power of nature, as well as the bond between mother and daughter. An Inuit woman creates a wall hanging filled with images of the spectacular Arctic landscape and traditional Inuit objects and iconography while her daughter looks on. Soon the boundaries between art and reality begin to dissolve. Gyu Oh, 2010, 4 min 39 s. National Film Board of Canada.

In the twentieth century, Europeans and Americans introduced many new goods, such as instant foods, rifles, snowmobiles, and wooden houses, that transformed the Inuit lifestyle. Even if their levels of comfort and wellness have increased, today the connection between Inuit and the land has weakened. In the early 1970s, Inuit formed the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami (ITK) to represent them and defend their interests in the face of mining, oil, and gas companies and governments wanting to use their land. Their negotiation led to the legislation that created the new territory of Nunavut, where they oversee how the land and water are used and how wildlife is managed and preserved. Thanks to the creation of several co-management bodies, and through the implementation of the Nunavut Land Claims Agreement, Inuit have the future well-being of the land and wildlife in their hands.

Inuit have had limited historical experience with mining in what is now Nunavut Territory. The first mine operated at Rankin Inlet in the Kivalliq region from 1957 until 1962, when international prices for nickel fell. Between 1978 and 2002, the Nanisivik Mine on the northern part of Baffin Island produced lead and zinc for the European market, and the zinc mine Polaris operated on Little Cornwallis Island. It produced 21 million tonnes of ore. Of the 250 employees, only 20—Inuit from Resolute Bay—were northerners.

There exists only limited literature on indigenous peoples and mining in the Arctic that has been written with the consultation and support of these communities. Most of the authors, apart from a few exemplary cases, register people’s dissatisfaction. Many of them make reference to the imposition of Western values through economic and political structures, while others underline the complicity between the government and extractive industries.

Historically, Aboriginals’ concerns about development projects are not only connected to the physical environment, but also to a wide range of social, economic, cultural, and health issues. In this extended perspective priority is given to reducing socioeconomic and sociocultural stress and racism, maintenance of traditional life based on hunting and gathering, combating social ills, and promoting personal development and confidence. Although people in the mining industry can access a degree of income security, the benefits of these projects are not distributed equally between the industry and those directly affected. Mining projects bring with them Western principles, including individualism, competition, and a belief that markets are the best way to organize social and economic affairs. These approaches create cultural friction and lack of understanding with cultures, such as indigenous cultures, that are centered on collective rights and collective awareness.

No. 46. Video of Caribou. Short video created by Elena Baldassari using Elders and hunters stories on Inuit traditions and relationship with caribou and drawing from the Tuktu and Nogak Project of the Kugluktuk Angoniatit Association (KAA). This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

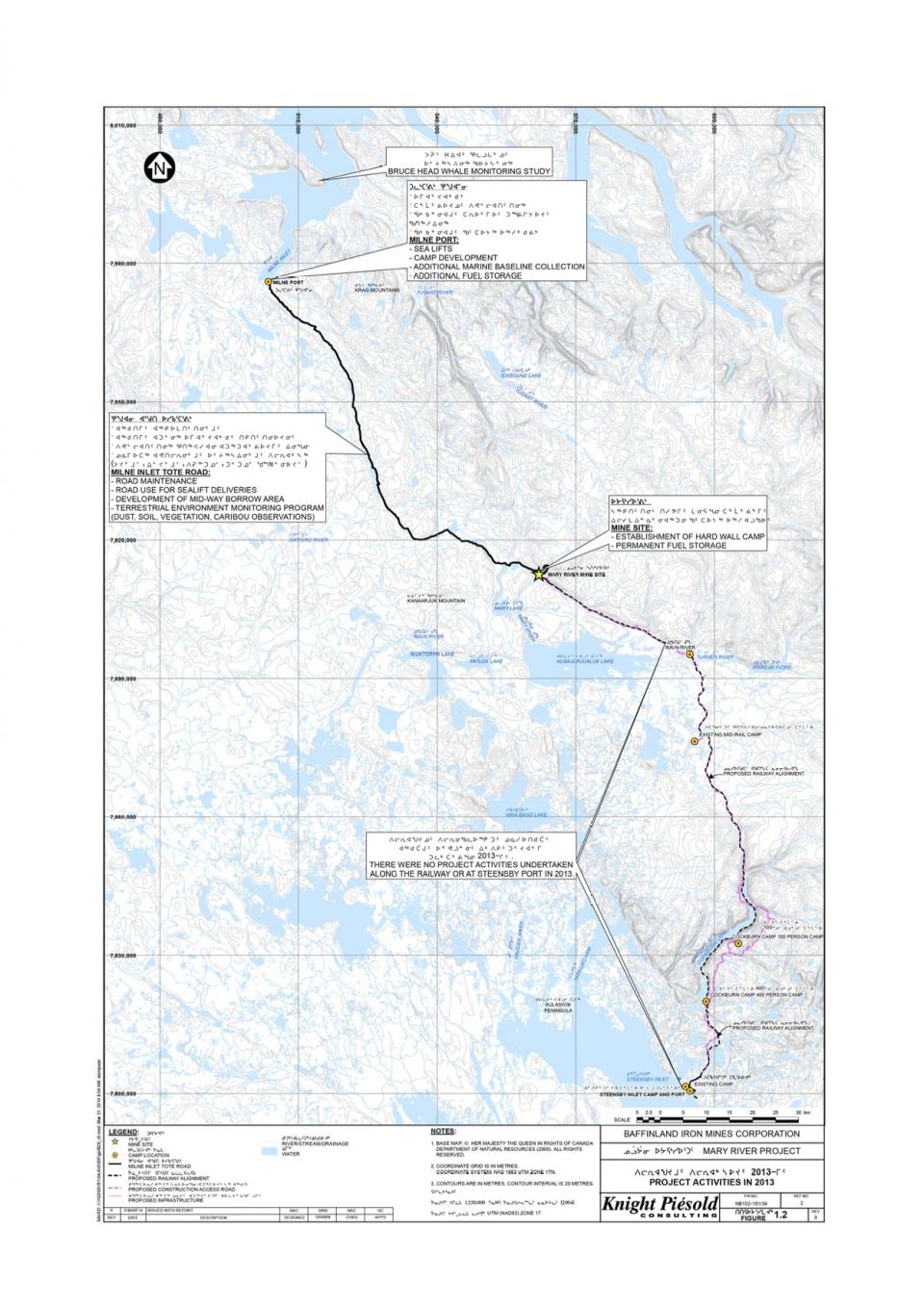

Mary River Project

The Mary River Project is an iron ore mine located on North Baffin Island in the Qikiqtani Region of Nunavut, which opened in 2014. It is one of the largest and richest undeveloped iron ore projects in the world, and involves the construction, operation, closure, and reclamation of an open pit mine. It is one example of a mining project proposed on Inuit-owned land, from which Inuit should receive significant mineral royalties.

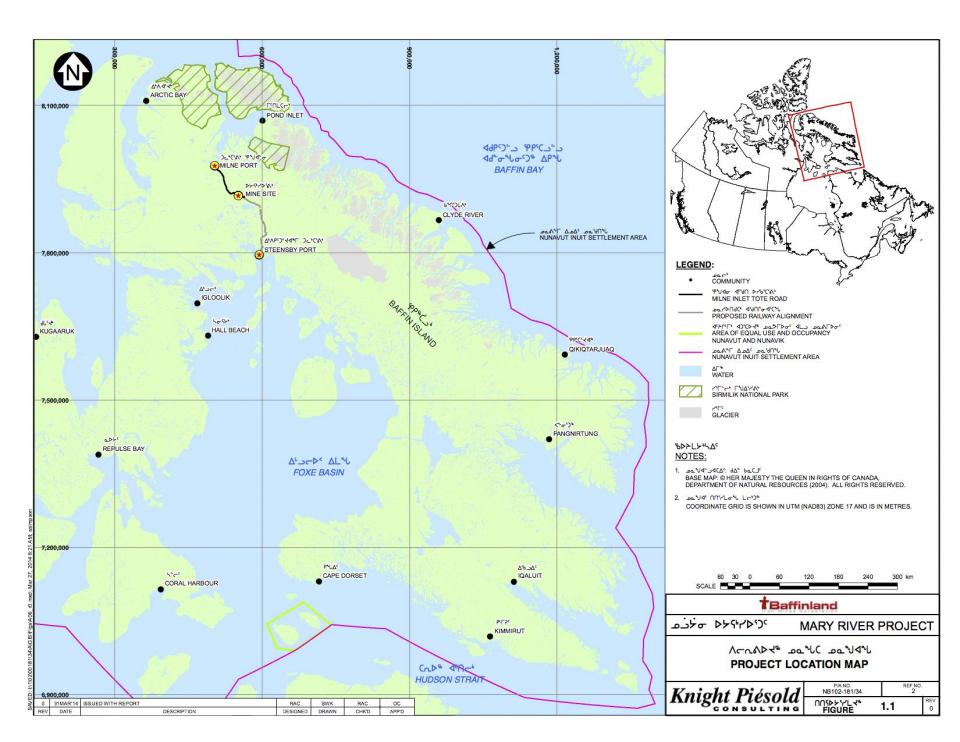

No. 47. Mary River Project. Map from the final environmental impact statement on Baffinland’s Mary River iron mine project. This image is a publically filed documentation, Baffinland Company, 2013.

The proposer was Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation, which, after many years of environmental reviews and negotiations, presented probably the most ambitious mining project undertaken in the Arctic. The Mary River Property contains approximately 365 million tonnes of high-grade, direct-shipping, lump and fine iron ore that can be mined, crushed, and screened with no other processing (tailings). Due to the purity of the ore, no chemical processing facilities are required for this project, reducing the overall impact on the environment. The iron ore consists mainly of hematite and magnetite.

Mary River is important both because of the scale of the project and as a precedent for mining in Nunavut. The first plan presented provided for the shipment of about 3.5 million tonnes of ore annually through a port at Milne Inlet: to this purpose the construction of a railway from the mine site to Steensby Inlet was considered. The 149-kilometer rail line should have operated year-round and posed huge engineering challenges, at a cost of two billion Canadian dollars. The construction—over environmentally sensitive and highly unstable permafrost—was supposed to take four years.

In addition, the project should have provided for a new port at Steensby Inlet from which iron ore should have been shipped through Foxe Basin or Hudson Strait throughout the year to Rotterdam and other European ports. The project was seen as an important form of financial security for the future, and for the Inuit it has the potential to be the economic driver for Baffin Island communities for decades to come.

No. 48. Mary River Project. Map from the final environmental impact statement on Baffinland’s Mary River iron mine project. The map shows the 149-kilometer rail line proposed that would connect the mine site to Steensby Inlet. This image is a publically filed documentation, Baffinland Company, 2013.

Nevertheless, to approve the project the Planning Commission had to hold public hearings to allow members of the public in Igloolik, Pond Inlet, Arctic Bay, Hall Beach, Clyde River, Kimmirut, and Cape Dorset to share their views and concerns about Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation’s proposal. Having reviewed and analyzed every aspect of the question, the project created an impressive detailed documentation of 15,610 pages in length and containing extensive technical data. The number of pages demonstrates the complexity of the effects of a project like this. Among the positive consequences are employment opportunities and greater income.

The final environmental impact statement (FEIS) prepared by Baffinland Iron Mines Corporation declared that between 800 and 2,700 jobs should be created during the construction and operational phases, mostly based at Mary River mine and Steensby port, not including the additional employment expected to be created indirectly due to the economic growth generated by the project.

On the other hand, it may have a negative impact on Inuit harvest activities and environmental protection, for the project interacts deeply with wildlife (as, for example, access and rail crossings). Another concern is the effect of shipping on marine environment. Most of the concerns are related to the “cumulative impact” of climate change as a challenge for mining activity.

Important, too, is assuring the preservation of the integrity of the ground surface, the protection of natural resources, and minimization of disturbances in several areas of permafrost management, including the building and stabilization of the mining area, the proposed railway, and the operation area.

Other concerns are connected to Inuit traditional life and community well-being. For this issue it is very important to highlight that if, for most people, earning a living is at the center of their lives—providing sustenance, reinforcing self-respect and community and family relationships—in Nunavut communities, harvesting is an essential aspect of earning a living. Modern harvesting is today integrated with the cash economy, and harvesting provides a social safety net for community members, a practical way to provide high quality food, and a respected and deeply valued form of work.

It is important to notice how “cultural” differences were sometimes used to excuse the failure of employment programs, as if “Inuit culture,” or rather the failure of that “culture” to change in the right direction, could impede the participation of Inuit in the new projects. These and additional concerns and questions were presented during hearings in 2012 that were designed to incorporate Inuit participation and knowledge into mining decisions.

By raising the level of informed participation and lowering the amount of secrecy involved in negotiations with mining companies, the Digital Indigenous Democracy project was created by Isuma TV. This system uses multimedia conversation as a key means of meeting the legal obligation to inform and consult with indigenous people. Isuma performed live audio broadcasts of the hearings, allowing anyone to listen to proceedings usually restricted to bureaucrats and industry representatives.

After years of technical meetings, public hearings, and thousands of pages of material describing the potential impacts of an iron mine on the Mary River, the supporter, Baffinland, finally received a project certificate to go ahead with the mine in December 2012. They announced, however, that because of slumping steel prices they had to scale back their proposal to a phased-in approach that would involve temporarily postponing construction of the railway to Steensby Inlet and its year-round port. Instead, they decided to ship only 3.5 million tonnes of ore a year out of the Milne Inlet, and only between July and October using a newly constructed tote road. The setback created great surprise and some suspicion between the interested hamlets and communities, so demonstrating the difficulty and complexity of harmonizing development, environment, profit, and traditional knowledge.

Conclusion

Like all peoples who have been, and remain, close to the land, Inuit are an optimistic and persistent people. Inuit regard all transformations in the Northwest Passage with concern and curiosity simultaneously.

Scientists and northern residents are witnessing increasing evidence of the direct impacts of the accelerated warming in this region. This warming, combined with changes in the natural and the socioeconomic environment, is having cascading effects on the ecosystem and society, with significant impacts on human health and quality of life. Like all peoples who have been, and remain, close to the land, Inuit are an optimistic and persistent people. As Terry Audla, the former President of Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, has stated, Inuit are also mindful of, and grateful for, the great joys and compensations of life and the mysteries that mix hardships and comforts together. Inuit regard all transformations in the Northwest Passage with concern and curiosity simultaneously. Climate change is a pressing issue because of its impact on Arctic wildlife and its potential to accelerate the loss of the traditional Inuit hunting culture. These effects are challenges that will concern tomorrow’s youth and the well-being of future generations. For these reasons it is urgent that elders and community members have the opportunity to contribute their Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit to a local and regional understanding of climate change. Many elders who were born and raised on the land and have decades of relevant knowledge, have already passed away, leading to the loss of their comprehensive understanding of climate change trends, impacts, and adaptations. Some efforts have been made to collect such a perspective, which will enhance a global awareness of climate change phenomena.

Many elders who were born and raised on the land and have decades of relevant knowledge, have already passed away, leading to the loss of their comprehensive understanding of climate change trends, impacts, and adaptations.

Inuit organizations such as Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. (NTI), Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami, and the Hunters and Trappers Organization (HTO) have organized and hosted several workshops to enable Inuit express their views before research agendas that are, in general, set on southern priorities. Inuit Qaujimajatuqangit and societal values deem the exchange of community-based and science-based knowledge around the same table to be the most useful approach.

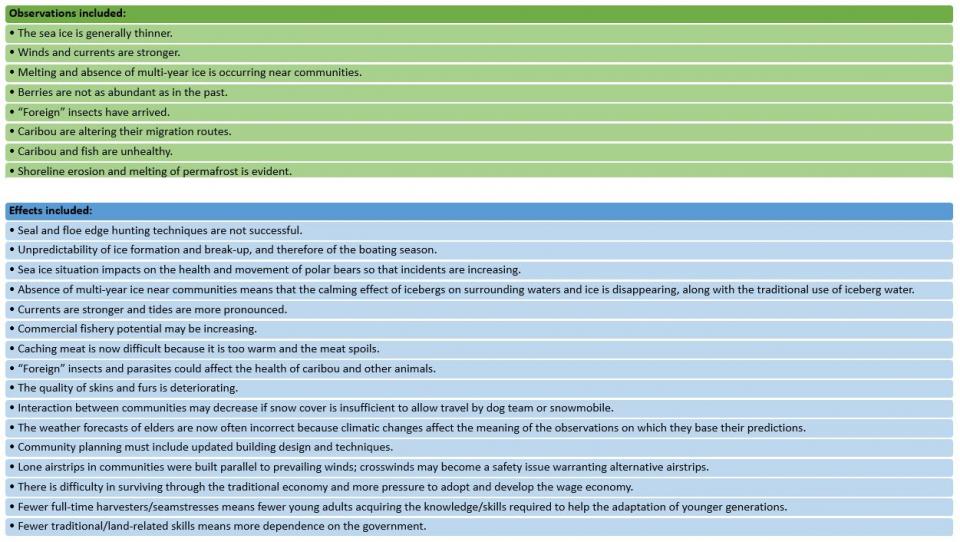

The following is a compilation of observations and concerns brought up repeatedly during several of these workshops:

Source: What if the winter doesn’t come? Report of a workshop held in Cambridge Bay, March 2001. Published online by the Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., May 2005.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

No. 49. What if the winter doesn’t come? Report of a workshop held in Cambridge Bay, March 2001. Published online by the Nunavut Tunngavik Inc., May 2005. This table was created by the Portal team and is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The issues are problematic, numerous, and ambiguous. As this exhibition shows, everyone involved has his or her own approach to these problems. A better understanding of these changing effects is necessary. Much can be learned of the changing conditions by observing animals—just as Inuit have done since the beginning of the time.