Beach at Cabo San Lucas, Tayrona National Park

Beach at Cabo San Lucas, Tayrona National Park

Photo by Claudia Leal, June 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Camping site at Cabo San Lucas

Camping site at Cabo San Lucas

Photo by Claudia Leal, June 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Tayrona, Colombia’s most cherished national park, is known for its gorgeous bays surrounded by tropical forests that creep up the foothills of the Sierra Nevada de Santa Marta. Covering 12,000 hectares of land and 3,000 hectares of sea, it contains archaeological ruins and coral reefs. This spectacular area attracts thousands of visitors; most of those who spend the night inside the park rent hammocks or use camping grounds offered illegally by several small businesses. More than fifty years have gone by since its designation, and the park service’s dream of controlling an uninhabited wilderness seems as elusive as ever. While it is tempting to conclude that this is just another “paper park” (existing only in government documents rather than in reality), its early history attests to the extent to which the area has been shaped by its protected status.

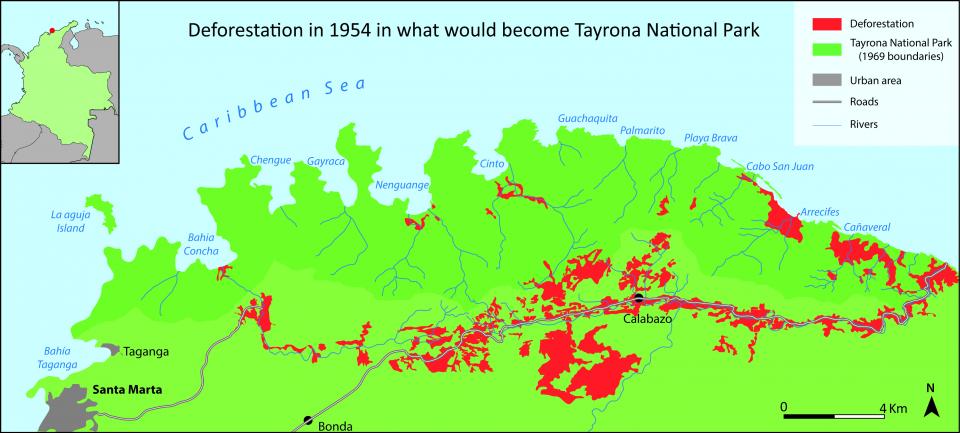

Deforestation in 1954 in what would become Tayrona National Park

Deforestation in 1954 in what would become Tayrona National Park

Map by Christian Medina and Carlos Leopoldo Gómez, Cartography Lab, Universidad de los Andes

Sources: Aerial photographs #2446-2451, flight M-27, 1954, Instituto Geográfico Agustín Codazzi, IGAC, and Superintendencia de Notariado y Registro and Unidad Administrativa Especial Sistema de Parques Nacionales Naturales (2012) “Situación jurídica actual del Parque Nacional Natural Tayrona (Propiedad, tenencia y ocupación)”, map p.6, 2012.

Note: not all the area depicted in the map was covered by the photographs, so deforestation outside of what later was designated as park is underestimated. The author thanks the IGAC for providing the photographs used to produce this map.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Between 1968 and 1970, the national environmental agency (Inderena) worked with other state institutions to clear the park from owners and residents. The Geographical Institute of Colombia (Igac) carried out a detailed land registry and appraised the plantings and work of over 200 peasant families who had settled in the area over the previous 20 years, mostly in the years before it was declared a park in 1964. Inderena evicted these families, who received sums that did not include the value of the land itself because of their lack of property titles. Peasants considered the payments preposterous and thought it unfair that the few titleholders were instead allowed to keep their properties. Despite threats of expropriating these larger landowners, the Institute of Agrarian Reform (Incora) was unable to do so for both political and financial reasons. Therefore, these properties within the park did not return to the public domain; worse still, the state was unable to actually enforce restrictions on private property. Notarial records from the park’s inception to 2012 show extensive land sales, building permits, foreclosures, and mortgages within the park—all of which are illegal and resulted from official confusion and corruption. Furthermore, as time went by, new settlers moved in and several people started offering food and lodging to tourists. Yet the park has been more than a dead letter: it eliminated cattle ranching and severely restricted cultivation. As a result, deforestation was reversed and today monkeys, foxes, rodents (including agoutis and pacas), and even some cats live in the area.

Jaguar (Panthera onca), Chengue, Tayrona National Park

Jaguar (Panthera onca), Chengue, Tayrona National Park

Camera trap photograph, 2012; Archivo Parques Nacionales de Colombia.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

While evictions made local people aware of the park’s existence, opposition to the plan to develop five-star hotels along the bays generated widespread controversy that turned the park into a national symbol. The National Tourist Corporation, created in 1968, designated Tayrona as the place in the country with most potential to attract affluent international visitors. This was part of a larger state attempt to turn tourism into a driving force of national development. In 1971, the Corporation proposed building hotels and cabins, along with commercial areas, parking lots, and recreational facilities, on some 780 hectares along the beachfront. Inderena disputed the plan and the clash made the headlines. One journalist asked:

To whom does this unique natural treasure… belong? To all Colombians… What does the government plan to do with this national property? Enclose it for the benefit of the grey-haired foreign tourists who will invade us as parrots from another world. (Samper 1972)

In 1973, the matter led to the first environmental debate in Congress. Finally, the following year, a new president buried the proposal of the National Tourist Corporation forever.

Although the state’s presence in the park is weak, Tayrona is a product of state policy. The environmental agency sided with some state institutions and confronted others in trampling peasants’ right to land and hindering agricultural and large tourist development on beachfront properties. These largely forgotten battles are behind the development of Colombia’s best known national park.

How to cite

Leal, Claudia. “More Than a ‘Paper Park’: Tayrona, a Caribbean Paradise.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2015), no. 6. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/6918.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2015 Claudia Leal

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Amend, Stephen, and Thora Amend, eds., National Parks without People?: The South American Experience. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN, 1995.

- Ojeda, Diana. “Green Pretexts: Ecotourism, Neoliberal Conservation and Land Grabbing in Tayrona National Natural Park, Colombia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 39, no. 2 (2012): 357–75.

- Rodríguez Becerra, Manuel. “Ecología y medio ambiente.” In Nueva Historia de Colombia Tomo IX Ecología y Cultura. Bogotá: Editorial Planeta, 1998.

- Samper Pizano, Daniel. “Un parque a dos aguas.” In El Tiempo, 27 May 1972.

- Silva Vallejo, Fabio and Deybis Carrasquilla. “Rescate de la memoria histórica del PNN Tayrona. Santa Marta-Colombia.” In Gestión del Conocimiento Tradicional. Experiencias desde la Red GESTC. Bogotá, 2008.