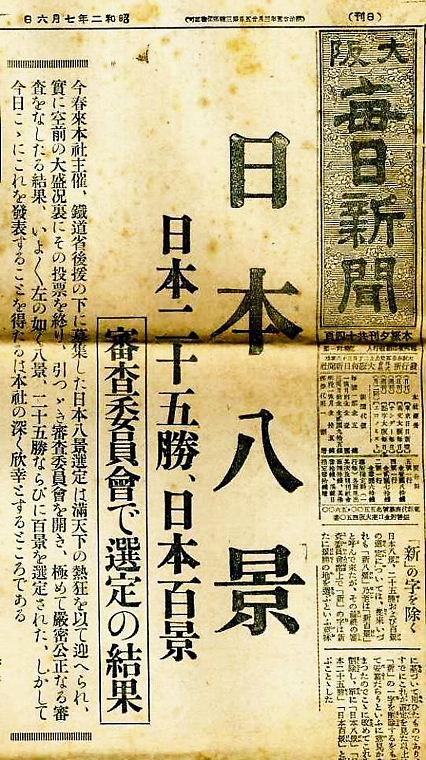

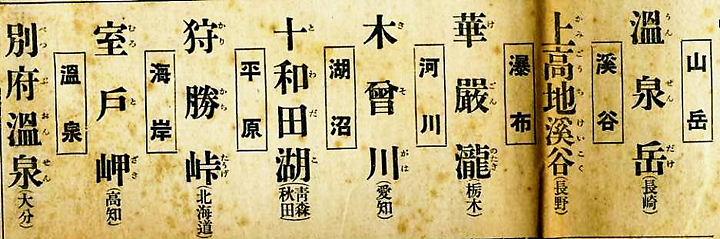

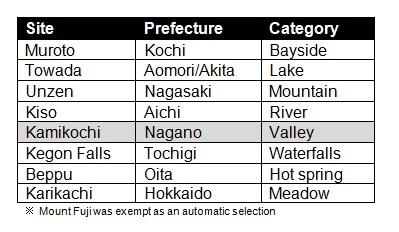

The final hakkei list of selected landscapes in 1927

The final hakkei list of selected landscapes in 1927

Graphic produced by Tom Jones.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Located at 1,500 m above sea level, the alpine valley Kamikōchi houses the headwater of the Azusa River. On either side, steep ravines rise to peaks of 3,000 m. This is the southern gateway to the Chubu Sangaku—the “Japan Alps.” Today it ranks among Japan’s ten most-visited national parks, with annual visitors peaking at 2.2 million in 1991, and is held in great affection today by climbers and sightseers alike.

And yet the valley was virtually unknown prior to 1927, when it was listed in a poll about Japanese landscapes. Conducted by two newspaper companies and backed by the Railways Ministry, the poll sought to determine Japan’s representative landscapes in eight categories, using a hakkei (八景) canon based on ancient Confucian cosmology. The first stage of the selection process consisted of a shortlist compiled from 93.5 million postcard votes by the general public. Next, a panel of experts deliberated for over 13 hours before the final list was published. Even though Kamikōchi had ranked a distant eleventh in the postcard vote, a powerful collection of elite interest groups helped it gain nomination in the final hakkei.

The 1927 hakkei marked the coronation of the new emperor Shōwa, heralding a new era that departed from static meisho (名所) traditions of fixed sightseeing circuits that centered on coastal vistas, shrines, and temples of literary fame. Unlike sacred mountains such as Hakusan or Tateyama, Kamikōchi was not renowned as a pilgrimage site. Kamikōchi’s swift rise symbolized a shift in landscape appreciation towards “modern” (i.e., Western) aesthetics and grand scenery accessible to the public. Among its most ardent advocates was Kojima Usui, a Yokohama banker who personified a new generation of wealthy climbers that envisaged Kamikōchi as the base for the new sport of alpinism. Kojima’s promotion of the valley as an “untouched wilderness” drew on a terra nullius rationale that exaggerated its remoteness. Influential foreigners such as Walter Weston helped forge this new culture into social networks such as the Japan Alpine Club (est. 1905), while alpinism (アルピニズム) also gelled with literary works such as Shiga Shigetaka’s Nihon Fukeiron (1894), an imperialistic travelogue.

Weston’s book (published in 1896) helped pave the way for Japanese alpinism

Weston’s book (published in 1896) helped pave the way for Japanese alpinism

Weston, Walter, Mountaineering and exploration in the Japanese Alps. London: J. Murray, 1896, iii.

Click here to view Internet Archive source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

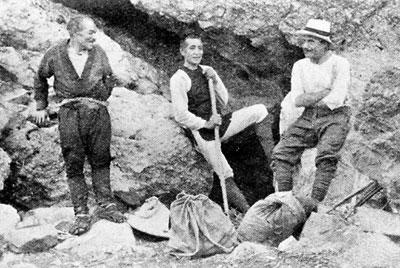

Walter Weston (right) with local guides Kamijo Kamonji (left) and Nemoto Seizou (center)

Walter Weston (right) with local guides Kamijo Kamonji (left) and Nemoto Seizou (center)

Weston, Walter, The Playground of the Far East. London: J. Murray, 1918, 164.

Photograph by Walter Weston.

Click here to view Internet Archive source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

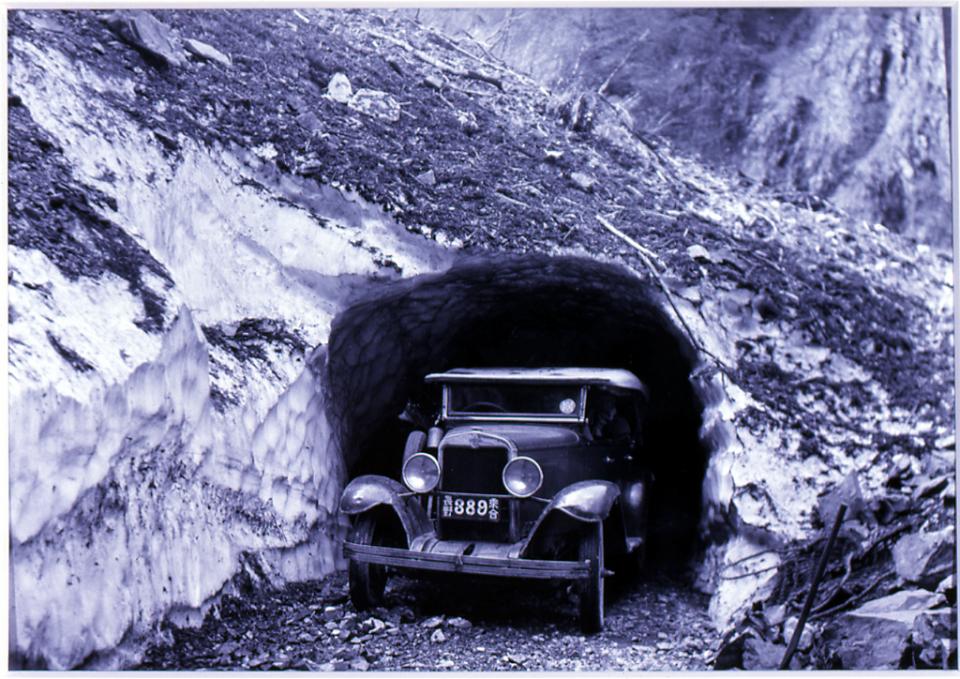

But the alpinists’ vision for Kamikōchi was just one of many planned developments, including livestock grazing, rice farming, and hydroelectric power generation. The balance tipped in favor of hydro after the eruption of Yakedake in 1915 when volcanic rubble blocked the Azusa, creating a natural levee. Extensive surveys re-emphasized the potential of hydroelectric power, but conservationists secured the valley’s designation as a forest reserve (1916) and national monument (1919). Nonetheless, legal protection did not safeguard the valley’s future and the Kama Tunnel was completed in 1924, enabling vehicle access to facilitate the construction of the Kasumizawa dam. However, the concurrent Keihin Denryoku development plan to create a large-scale dam by flooding the valley galvanized an unlikely conservation alliance of aristocrats, academics, mountaineers, and bureaucrats. Powerful planners and landscape architects such as Tamura Tsuyoshi insisted tourism was the only feasible alternative to hydropower, and media campaigns such as the hakkei thus became an important PR tool to educate the public about opportunities to explore Japan’s ‘new’ landscapes.

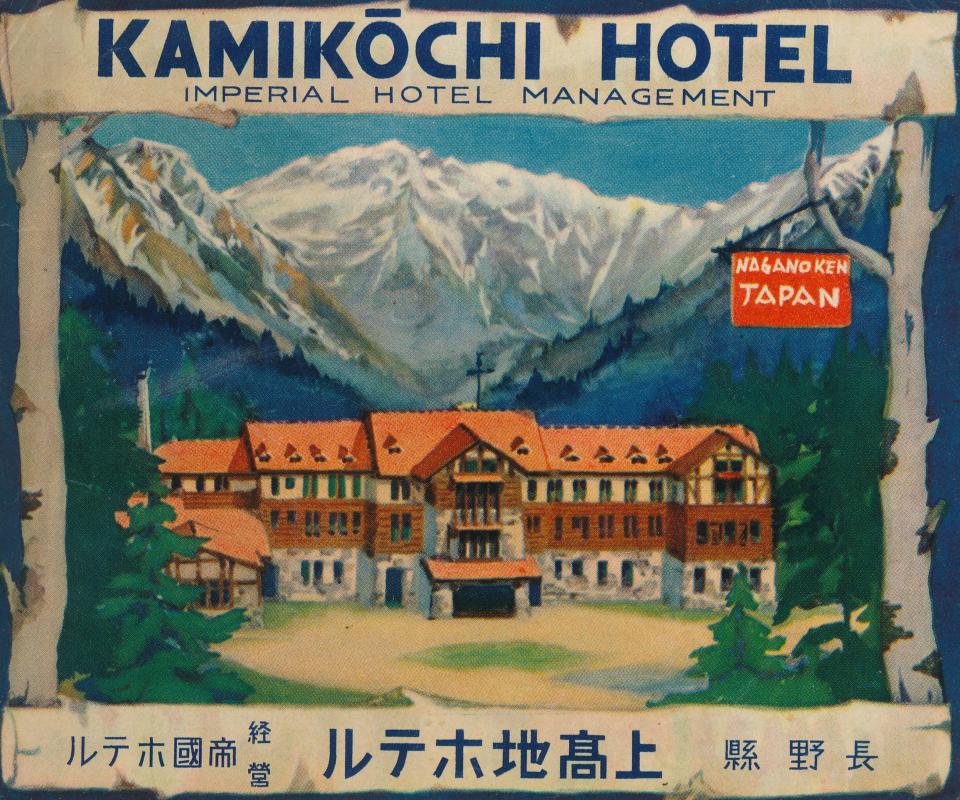

The Imperial Kamikochi Hotel, completed in 1933 with the help of funding from the Ministry of Finance

The Imperial Kamikochi Hotel, completed in 1933 with the help of funding from the Ministry of Finance

Courtesy of the Imperial Hotel.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Tourism helped raise awareness of Kamikōchi’s plight and rally support against the construction of large-scale hydropower dams, as had occurred at Kurobe further north in the same mountain range. The pragmatic campaigning tactics that sealed Kamikōchi’s hakkei nomination would subsequently be scaled up to mobilize a cross-section of stakeholders into creating the inaugural national park law (1931). Grand, mountainous landscapes such as Kamikōchi formed an integral part of the new tourism-based national park system. Infrastructure development was promoted along the lines of the ‘Yellowstone model,’ and ‘international standard’ hotels were constructed, funded by low-interest, long-term loans from the Finance Ministry. By the time the Japan Alps was designated among the first batch of national parks in 1934, visitors could stay in the Kamikōchi Imperial Hotel, a luxurious Swiss-style lodge, and a regular bus service was also in operation to the ‘most beautiful valley in Japan’.

How to cite

Jones, Tom. “’The Most Beautiful Valley in Japan’: Kamikōchi, the Japan Alps, and National Parks in Japan.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2016), no. 8. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7600.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2016 Tom Jones

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Jones, Thomas. "The Role of the Shin Nihon Hakkei in Redrawing Japanese Attitudes to Landscape." In Environment, Modernization and Development in East Asia, edited by T.-J. Liu, and J. Beattie, 139-56. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 2016.

- Manzenreiter, Wolfram. “Die soziale Konstruktion des japanischen Alpinismus: Kultur, Ideologie und Sport im modernen Bergsteigen.” PhD diss., University of Vienna, 2000.

- Murayama, Kenichi. “Kamikōchi in the Early Showa Era: The Exploitation of Water-Power Resources, Conservation of Nature and National Parks.” Regional Branding Research 4 (2009): 4.

- Tanaka, Seidai. Japan’s Nature Parks: Conservation of Nature and Landscape. Tokyo: Sagami Publishing, 1981.

- Tarō, Nitta. “Selecting Japan’s Eight Landscapes: Tourism and Media Events in 1920s Japan.” Keio School of Art Bulletin 18 (2010): 69-84.

- Wigen, Kären. “Discovering the Japanese Alps: Meiji Mountaineering and the Quest for Geographical Enlightenment.” Journal of Japanese Studies 31, no. 1 (2005): 1-26.