Managing Waste

Waste calls us to action—we cannot let it accumulate. Eventually, we notice and smell the presence of heaps of trash and consumer durables and we feel we need to do something about it: we burn it, bury it, dispose of it, discard it, reuse it, or recycle it. In short, we try to take care of it.

These myriad practices transform the waste object as well as our relationship to it. On the one hand, they reallocate value to trash. Recycling, for instance, subjects waste to the laws of profit and exchange and creates new markets. When you donate the clothes you no longer want instead of trashing them, charities usually sell the best items, usually a small number, at their thrift shops. The rest they sell to textile recyclers, who then recycle your clothes into cleaning cloths. Alternatively, textile recyclers sell the clothes to other countries around the world. A donated dress from Japan may in this way end up at a second-hand store in Israel. On the other hand, managing waste practices fundamentally redefines how waste figures in our connection with our body. Take, for instance, the anti-litter campaigns that started in the late 1960s in several Western countries. They transformed trash from matter out of place into morally unsettling evidence of the collapse of civic obligation, according to Gay Hawkins.

The campaigns initiated a major shift from disposal as elimination to disposal as a process of waste management. Recycling, composting, and reusing inaugurated new habits and rituals. Fulfilling their civic duty, people started handling their empty bottles differently from their old newspapers. As they rinsed and sorted their trash, they became environmentally aware and, ideally, careful waste managers. “Keep Britain Tidy” is just one of the many campaigns that emerged during that time. After more than 50 years, the slogan is still used to educate the British to litter less.

Berlin induces its citizens to proper waste disposal through canny slogans on its waste containers. Photograph by author, 2015.

Berlin induces its citizens to proper waste disposal through canny slogans on its waste containers. Photograph by author, 2015.

Photograph by Simone Müller (author), 2015.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

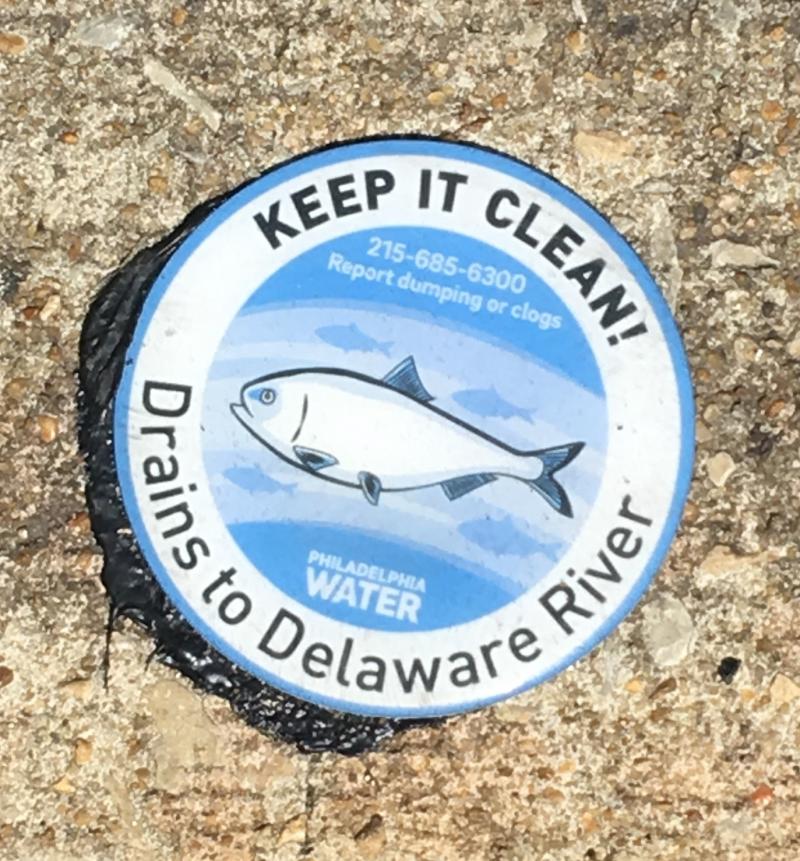

Philadelphia encourages the public to keep drains clean and unclogged. Photograph by author, 2018.

Philadelphia encourages the public to keep drains clean and unclogged. Photograph by author, 2018.

Photograph by Simone Müller, 2018

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Berlin, in turn, uses funny slogans on their waste containers to make disposing fun. Philadelphia, similarly, marks its drains with quaint images of water animals telling its citizens which way the waste flows.

Public cleaning initiatives and waste management more generally vary across countries and communities. In The Business of Waste, Raymond Stokes, Roman Köster, and Stephen Sambrook explain the differences in waste management in Great Britain and West Germany after World War II. The authors illustrate how the two countries took profoundly different paths from low-waste to throwaway societies, and more recently toward the goal of zero waste. Bringing in a perspective from Brazil, Jutta Gutberlet extrapolates the particularities of waste management from the Global South—a world region where people’s lifestyles are not yet “cocooned in the consumption bubble,” she says. Quite the contrary, informal and cooperative recyclers in Brazil, the cartadores, have developed effective practices and policies supporting the circular economy, sufficiency, and solidarity.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of book and film profiles and articles showcased on the Environment & Society Portal. View the individual gallery items online or in the appendix of this PDF.

The rise of consumerism in the UK and West Germany after 1945 led to a mass production of garbage. The countries are similar, but took different paths from low-waste to throwaway societies, and recently, towards the goal of zero-waste. The authors explore the relationship between public and private provision in waste services, the role of government, and the effects of globalization. (Adapted from Cambridge University Press)

Learn more

Poison in the Well examines policy decisions, scientific conflicts, public relations strategies, and the myriad mishaps and subsequent cover-ups that were born out of the dilemma of where to house deadly nuclear materials. Hamblin traces the development of the issue in Western countries from the end of World War II to the blossoming of the environmental movement in the early 1970s. (Adapted from Rutgers University Press)

Learn more

The challenge of dealing with urban wastes has taxed the minds of scientists, engineers, and public officials. Tarr’s essays explore solutions to waste disposal and policy issues involved in the trade-offs among public health, environment, and the difficulties and costs of pollution control; all this while facing changes in civic and professional values. (Adapted from University of Akron Press )

Learn more

Jennifer Clapp examines the nature of international trade in toxic waste and the roles of multinational corporations and environmental NGOs. Waste transfer has become a routine practice for firms in industrialized countries. Poor countries have accepted these imports but struggle to manage the materials safely. Clapp argues that governments have failed to recognize the voices of protest. (Adapted from Cornell University Press)

Learn more

The idea of zero waste requires shifts in cultural values rather than new technological solutions. The inspiration for sustainable waste policies will likely come from the Global South, where consumerism and discard-oriented production are not yet fully developed, economies are less fixated on growth, and people’s lifestyles aren’t “cocooned in the consumption bubble.” (Adapted from author’s abstract)

Learn more

As a space where terrestrial jurisdiction did not apply, the ocean was a convenient solution to messy problems that nobody wanted; unwanted things could simply be loaded onto a ship and sent away. Using the image of the legendary ghost ship, the Flying Dutchman, this article traces the journeys of several ships and their cargos of toxic waste in the 1970s and 1980s. (Adapted from author’s abstract)

Learn more

Waste is never “out of sight.” Once discarded, it undergoes transformations, often reappearing elsewhere in new forms. Scholars investigate the traces waste leaves behind in the course of its travels. The essays follow the journeys of unwanted substances and unusable objects by studying how they have transformed landscapes, ecosystems, and even the human body. (Adapted from the Environment and Society Portal)

Learn more

Although we cannot let trash accumulate, we rarely want it nearby when it does. Trash seldom stays close to its place of origin. Rather, waste has an inbuilt mobility as we try to move the material out of sight. We throw it into bins, flush it down the drain into the sewage system. Prior to filter systems, industries built higher chimneys to reduce local emissions by transporting their air waste further away. Today, plans of opening up a new waste disposal facility, be it an incinerator, a sewage-treatment plant or a landfill, are often accompanied by cries of NIMBY (“not in my backyard”). Concerned citizens point out that the waste disposal may have detrimental effects on the neighborhood. Finding the right disposal spot has proved particularly difficult for nuclear waste, as this 1985 quote from an anonymous Earth First!er demonstrating against the Canyonlands Nuke Dump illustrates:

We are here to make it clear that there are many people, of which we are but a handful, unwilling to abide by your demented “decision-making process” which continues to consider establishing a nuclear waste dump in one of the most fragile and beautiful places on the planet, thereby killing it and threatening everything around and downriver from it.

— Anonymous Earth First!er in Earth First 5, no. 4

Over the years, the rather selfish cry NIMBY—not in my backyard—has transformed into NIABY—not in anyone’s backyard—as activists have worked to establish a strong solidarity between communities and countries all across the world. Little did these debates acknowledge, however, that the trash has to go somewhere. Now.

While most of our trash is managed close to its source, starting in the 1960s and 1970s, some of the material began traveling over large distances to reach its disposal grounds. Communities started hauling their trash to the next county, the next state, the next country, and even the next continent. About 10 percent of the hazardous waste that industrial countries produce crosses nation-state borders for its disposal, Jennifer Clapp documents in her book Toxic Exports. While much of this waste trade happens within OECD countries, some goes to countries of the global South. Not all schemes are legal. Most are ethically doubtful. The importing countries may offer cheaper deals, but do not always own facilities to dispose of the material in an environmentally sound or healthy manner. They, in turn, face a choice between being poor and being poisoned. Since the 1990s, activists opposing the trade have cried out “Garbage Imperialism” and bemoaned a “recolonization” of the world through trash.

The research group Hazardous Travels: Ghost Acres and the Global Waste Economy investigates the structures and dynamics of this global waste economy through case studies from the United States, Germany, India, and Ecuador. Follow them on twitter if you want to learn more about their research.

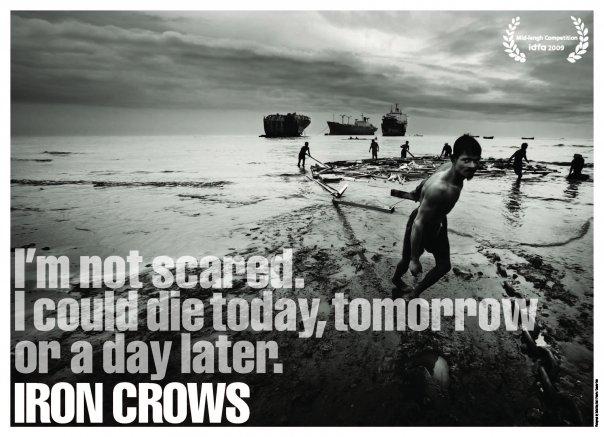

Watch the movies Eisenfresser [Ironeaters] or Iron Crows to learn about ship breaking—one of the world’s most prominent examples of waste relocation. Since the 1980s, the world’s largest ship breaking industry has been situated at India’s West coast, and by now moved up to Bangladesh. Here, people recycle industrial countries’ shipping fleets for little money. This business is highly controversial. Shipbreakers work with their bare hands and often little protection gear to break the ships apart. Their work is dangerous and their health impaired, and refuse often seeps directly into the ground. Yet, every single part of the ship is reused and recycled, from the iron body parts to the asbestos and interior design elements it contains. The industry, in turn, fights hard to shed its bad image.

At the market in Alang, vendors sell everything usable from the dismantled ships, ranging from cutlery and antiques to lifeboat provisions. Photograph by Ayushi Dhawan, 2018.

At the market in Alang, vendors sell everything usable from the dismantled ships, ranging from cutlery and antiques to lifeboat provisions. Photograph by Ayushi Dhawan, 2018.

© 2018 Ayushi Dhawan.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In the end, we are always on the lookout for what Joel A. Tarr terms the ultimate sink in his book The Search for the Ultimate Sink, the optimal solution for the disposal of our trash. Yet, for some materials, such as nuclear waste, there is no such thing as the ultimate sink. As you accompany filmmaker Edgar Hagen on his quest around the world to find “the safest place” for the remnants of nuclear activity, consider possible alternatives. Should we not be able to find other solutions?