It is reckoned that during the 1877–1878 Russo-Ottoman War, the number of soldiers who died from epidemic disease, starvation, and cold exceeded the number of soldiers who died in combat. The war ended with a devastating defeat for the Ottoman Empire, nullifying its claims on the Balkan peninsula which the Ottomans called “Rumelia.” As Russian troops advanced, the Muslim population in the Balkans set off a huge wave of refugees. Among them, it is estimated that the number of victims of infectious diseases exceeded the number of victims of the occupying army. Among those diseases, typhoid fever, a bacterial infection characterized by essential pathologic lesions in the intestines, mesenteric lymph nodes, and spleen, stands out as a prominent culprit.

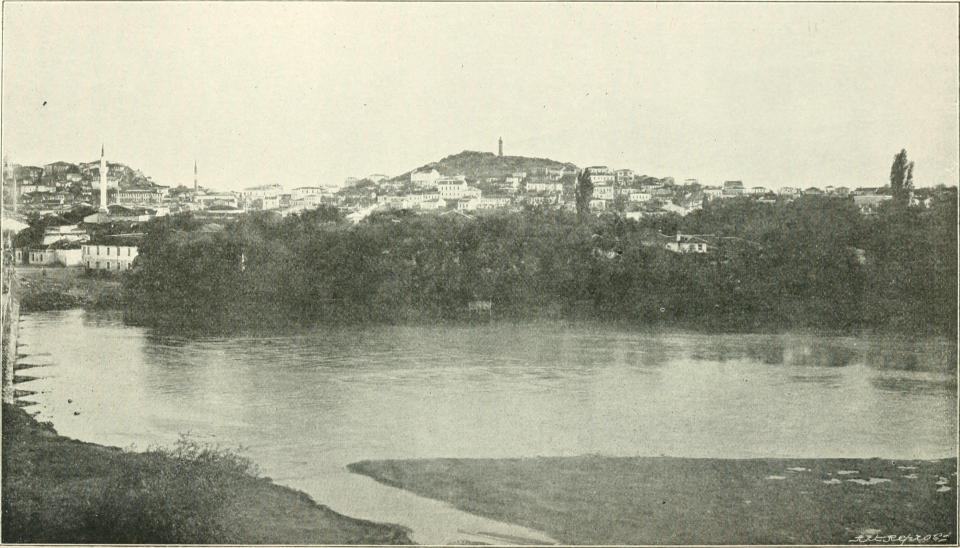

Phillipopolis in the 1890s.

Phillipopolis in the 1890s.

Unknown photographer, 1890s.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 1 December 2020. Click here to view source.

Originally published in William Miller, Travels and Politics in the Near East (New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company, 1898): 438.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

During the War of 1877–1878, Philippopolis (currently “Plovdiv” and formerly “Filibe” for the Ottomans) was a large Balkan town of about forty thousand inhabitants with strategical importance, where many wounded Ottoman soldiers were transported from nearby battlefields. According to Dr. R. B. Macpherson, a Scottish humanitarian surgeon who visited Philippopolis in late 1877, “surrounded by low, marshy ground,” the town had an “unhealthy character.” In October 1877, a correspondent of The Times witnessed the deficiency of stores and medicines, the abundance of parasites on the people, and the overwhelming number of patients in hospitals in Philippopolis. He was convinced that “matters could hardly be worse.” There were 16 hospitals, all of which were indeed public buildings and larger private houses made use of for the purpose, and among which a thousand patients were apportioned. The correspondent was not expecting “affairs to improve” at all but rather thinking that “the plague, cholera, or typhoid fever of an aggravated character [might] at any moment break out.” The latter’s estimate was endorsed by the observations of a British officer who visited the town a month later. Colonel Burnaby reported that there were “a great many wounded men,” and added, “[m]any of the patients were suffering from typhoid fever.”

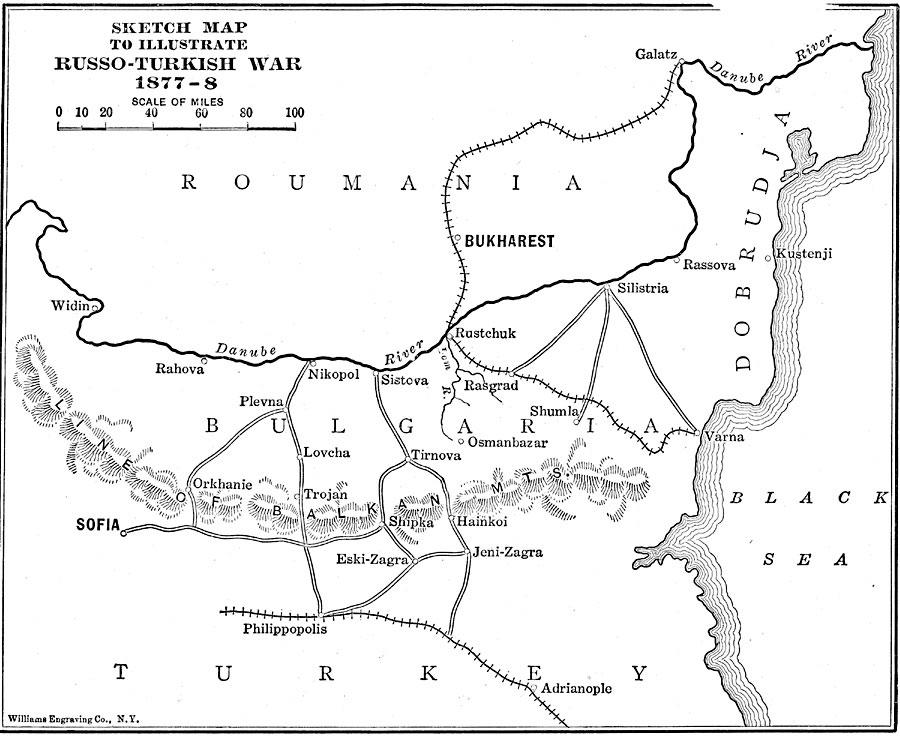

Map illustrating the Russo–Ottoman War, 1877–1878.

Map illustrating the Russo–Ottoman War, 1877–1878.

Map by Williams Engraving Co., 1918.

Courtesy the private collection of Roy Winkelman and the Florida Center for Instructional Technology (FCIT).

here to view source.

Originally published in Lucius Hudson Holt, The History of Europe from 1862 to 1914, (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1918): 198.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Philippopolis was occupied by the Russian army on 17 January 1878. Dozens of thousands of refugees escaping from other occupied cities had sought refuge in Philippopolis before the Russians arrived. Eventually, many of them fled from the conquering army and headed for Thessaloniki, Anatolia (Asia Minor), and other parts of the Ottoman Empire. In February, fewer than fifteen thousand refugees, almost all of which were Muslims, while a few were Romani people, remained in the town. They were crowded in an isolated quarter and subjected to numerous mistreatments by the occupying forces. Meanwhile, Philippopolis continued to receive wounded and sick soldiers, this time from the ranks of the Russian army. All along the spring, the constantly-arriving fresh Russian troops headed east, for Adrianople (Edirne), to replace the tired troops deployed there, whereas the latter were transported to Philippopolis. The town had witnessed a great human mobilization in no more than a few months. Soon, it turned out that another conquest was on the way. Troops of typhoid bacteria, equipped with deadly weapons, were about to seize the town.

The raging fever in Philippopolis made no distinction between soldiers and civilians. According to accounts transmitted from the town and published by the Ottoman press in April, the Maritsa River was filled with corpses of the victims. Their removal from the river and burial had become a main task for the Russian forces. In May, heavy rainfall and floods worsened the situation by opening the graves. The unbearable smell prevailed over the town. The Ottoman newspaper Tercüman-ı Şark claimed that hospitals in the town were full of people suffering from typhoid and estimated that each day 15 of them were losing their lives. A letter written from Philippopolis on 18 May to the Austrian newspaper Neue Freie Press (19 May 1878) asserted that the disease continued to trouble the town. The number of patients in the hospitals was 2,700 and marked a considerably high number given the rapidly shrinking population because of war, migration, and epidemics. Assuming that the town’s population had fallen to about twenty thousand by the time the letter was written, the unknown writer was calculating that more than 10 percent of the town was infected with typhoid fever. Unfortunately, articles published by the contemporary press are mostly far from providing us coherent and specific information about victims of the fever and policies implemented to defeat it in the spring of 1878.

Plovdiv (Philippopolis) in 2008.

Plovdiv (Philippopolis) in 2008.

Photograph by Klearchos Kapoutsis, 2008.

Accessed via Flickr on 1 December 2020. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

Signs of recovery emerged in summer. In July, an English correspondent reported from Philippopolis that mortality finally decreased from three to one percent per day. The fever was no longer “of the former malignant type.” Apparently, the disease noticeably lost its might before autumn. Though losing pace, it seems that the typhoid disease was not totally eradicated but continued to bother the town and the greater region for a long time. According to medical reports prepared in May 1879 about Bulgarian battalions in Philippopolis, typhoid fever still held its place among chief health complaints in the town a year later.

There is no reason to consider postwar urban epidemics of 1878 as an unexpected outcome of the war. In addition to limited access to clean water and food, non-ceasing massive human mobilization favored the spread of typhoid fever in a vast region from the Caucasus to Central Europe. In the meantime, germs were more than ready to aggravate the existing politico-economic disturbances by contaminating a considerably large part of the human population.

How to cite

Usta, İbrahim Can. “The Typhoid Epidemic in Philippopolis, 1878.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2020), no. 46. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9166.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 İbrahim Can Usta

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Kyurkchiev, Nikolay V. “Medical Statistics from Hospitals Establishments of Subdivisions of Military Troops from Composition of the Eastern Rumelian Militias, 1879. General Notes.” Biomath Communications 4, no. 2 (2017): 1–27.

- Macpherson, R. B. Under the Red Crescent: Or, Ambulance Adventures in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. London: Hamilton, Adams & Co., 1885.

- Özdemir, Hikmet. The Ottoman Army, 1914–1918: Disease and Death on the Battlefield. Translated by Saban Kardaş. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2008.

- Patterson, K. David. “Typhus and its Control in Russia, 1870–1940.” Medical History, 37 (1993): 361–81.

- Schulze-Tanielian, Melanie. “Disease and Public Health (Ottoman Empire/Middle East).” In 1914–1918-online. International Encyclopedia of the First World War, edited by Ute Daniel et al. Berlin: Freie Universität Berlin, 2014. doi:10.15463/ie1418.10466.

- Yavuz, Hakan M., and Peter Sluglett, eds. War and Diplomacy: The Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 and the Treaty of Berlin. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2011.