In June 2018, a majority in the Danish parliament voted in favor of establishing a 70-kilometer-long fence along the Danish-German border to prevent the migration of wild boars (Sus scrofa) and the spread of African Swine Fever (ASF). Work on the fence started in January 2019 and was completed in December the same year.

The process of fencing to limit the risk of wildlife diseases has long been a contentious topic among pig farmers, environmental organizations, politicians, and borderland communities. The perceived risk and economic consequences for the Danish pork industry loom large in this debate—the country is among the world’s leading exporters. Besides the economic risks of the transmission of ASF, wildlife fencing to prevent the intrusion of so-called feral species stimulates discussions of multispecies politics and feeds into more general debates about environmental politics and “invasive” others.

The wild boar was originally native to Denmark but was eradicated in the early 1800s due to intensive hunting and forest clearing. Wild boars have, however, since returned to Denmark and their belonging in the natural landscape has been a much-debated topic. Proponents perceive wild boar as an asset to Danish nature, since their rummaging in the forest floor helps to increase biodiversity. While farmers in principle agree with this, they mainly consider wild boar an unwelcome nuisance, as they scour through agricultural land and destroy crops. Because of their potential to carry diseases, and possibly transmit them to domestic pigs, the Danish government in 1995 permitted the shooting of a small sounder (family group) of free-ranging wild boar in Lindet forest in Southern Jutland. Since then, the eradication order became nationwide and today, the Danish Nature Agency is required to shoot wild boar migrating into Denmark to keep the country wild-boar-free. Wild boar crossing the border from Germany were specifically targeted, to prevent the opportunity for wild boar to reestablish themselves in Denmark.

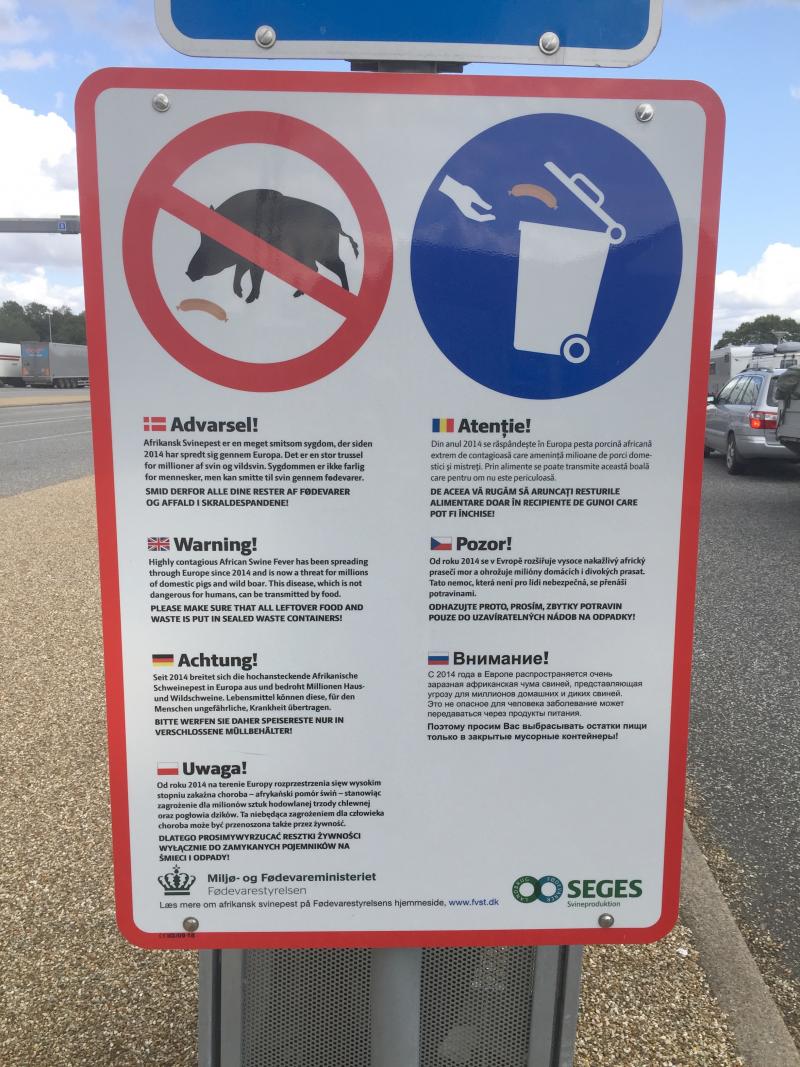

Fig. 2. Signboard situated at a Danish highway rest area warning travelers about the risk of African Swine Fever transmission.

Fig. 2. Signboard situated at a Danish highway rest area warning travelers about the risk of African Swine Fever transmission.

© 2021 Michael Eilenberg. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

ASF was first introduced into Europe in 1957, when it arrived in Portugal from the Portuguese colonies in Africa. From there it spread to western Europe but was completely eradicated in 1995, except on the island of Sardinia where it became endemic. However, the virus later became permanently established in mainland Europe after an outbreak in Georgia in 2007, where contaminated pork and pig feed was shipped in and fed to domestic pigs. From here it spread to neighboring countries and entered the EU. While Germany, among other nearby countries, has experienced ASF incidents, Denmark has maintained its ASF-free status. In the absence of a vaccine, biosecurity measures, such as fencing, are seen by both the rest of EU and the Danish government as a crucial element in preventing the introduction and spread of ASF.

Although narratives justifying the border fence are focused on external factors such as ASF, it is argued that the fence is more than just a biosecurity defense against external threats. Wild boar prefer to live in moist, shady, and wooded areas, which are mostly found along the eastern part of the border. Since the fence spans the entire length of the border, which in the west is dominated by open marsh landscapes and moorland, it has fueled criticism that the barrier is equally about symbolism and political imaginaries. Thus, the construction of the fence has been perceived by some as yet another advance toward tightened border control following the 2015 Syrian refugee crisis, which instigated fear of future uncontrolled migration across the Danish border.

Fig. 3. Photograph of the westward end of the wild-boar fence where it reaches the North Sea.

Fig. 3. Photograph of the westward end of the wild-boar fence where it reaches the North Sea.

© 2021 Michael Eilenberg. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The current location of the Danish-German border dates back only 100 years, as it has been historically contested, with national minority populations living on both sides. In recent years it has often been highlighted as an exemplar of harmonious borderland coexistence, as cross-border collaborations are plentiful and so are interpersonal networks. However, uncertainties about the fence, as yet another symbol of isolationism following the reintroduction of passport control and border guards in 2016, has made an impact. In local and international media and cross-border political debates, the fence was seen as a setback for the positive development of social and cultural exchange in the Danish-German borderland since World War II, and unfortunately intersects with the highly polarized migration debate in Denmark.

The last decades have witnessed a proliferation of border fencing across the globe. Denmark’s move has generated plenty of interest on social media, sparking sarcastic comparisons with Donald Trump’s border wall between the US and Mexico. The fence is a source of unease for the national minority populations on both sides of the border. Sensitivities over ethnic divisions and national boundaries remain and are seemingly accentuated by the fence. Anxieties over the stretching and tearing of the social fabric; the economic strain communities are experiencing; a heightened sense of uncertainty; and a polarization of secured and nonsecured spaces, places, and people at the border are all public discussions generated by the establishment of the fence.

Fig. 4. Photograph of the fence alongside a forest road in Krusaa in southeastern Jutland.

Fig. 4. Photograph of the fence alongside a forest road in Krusaa in southeastern Jutland.

© 2021 Annika Pohl Harrison. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

While some support the fence because they fear that ASF would destroy their livelihood, critics say that the construction of the fence is against EU regulations and harms wildlife. Others argue that the fence is purely a symbolic gesture tackling a largely nonexistent problem.

Nevertheless, supporters and opponents of the fence respectively have continued their defense and critique of this boar-der barrier and have enhanced the debates about the future role of wild species in Denmark, while keeping the prominent and deep-rooted agricultural sector risk-free and secure.

How to cite

Eilenberg, Michael, and Annika Pohl Harrisson. “Boar-der Fencing: Human-Animal Conflicts in the Danish Borderlands.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2023), no. 8. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9610.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2023 Michael Eilenberg and Annika Pohl Harrisson

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Bingham, Nick, Gareth Enticott, and Steve Hinchliffe. “Biosecurity: Spaces, Practices, and Boundaries.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 40, no. 7 (2008): 1528–33. doi:10.1068/a4173.

- Broz, Ludek, Aníbal Garcia Arregui, and Kieran O’Mahony. “Wild Boar Events and the Veterinarization of Multispecies Coexistence.” Frontiers in Conservation Science 2, no. 110 (2021): 711299. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2021.711299.

- Collier, Stephen J., Andrew Lakoff, and Paul Rabinow. “Biosecurity: Towards an Anthropology of the Contemporary.” Anthropology Today 20, no. 5 (2004): 3–7. doi:10.1111/j.0268-540X.2004.00292.x.

- Wilson, Thomas M., and Hastings Donnan. Border Identities: Nation and State at International Frontiers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Yamamoto, Dorothy. Wild Boar. London: Reaktion Books, 2017.

- Mysterud, Atle, and Christer M. Rolandsen. “Fencing for Wildlife Disease Control.” Journal of Applied Ecology 56, no. 3 (2019): 519–25.