Avocado Heights is an unincorporated majority-Latine community of 13,000 residents. Located in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles County, the neighborhood might blend seamlessly into the suburban-industrial sea if not for one distinctive feature—in Avocado Heights, pedestrians, bicyclists, and cars share the roads with horses. Residents use horses to take their children to school, travel to social events like weddings and parties, and enjoy the equestrian arena at the local park. Avocado Heights was declared an official equestrian district in 1991, one of seven in Los Angeles County and one of two with a working-class population. As Latine, specifically Mexican, immigrants moved into San Gabriel Valley, they introduced and spread their equestrianism, or charrería, to places like Avocado Heights. Their human-animal relationships and culture transcended borders and brought an equestrian identity to a Los Angeles suburb and, in the process, altered its environment.

Avocado Heights was an agricultural site for walnut and avocado cultivation sparsely populated with white, Mexican, Mexican-American, Chinese, and Chinese-American residents until the post-World War II period. After the war, Los Angeles city Latine residents and immigrants began moving to the San Gabriel Valley. While most of these newcomers incorporated their communities and put themselves into positions of local power, the residents of Avocado Heights followed a different path. During the 1950s and 1960s, communities in the San Gabriel Valley and Greater Los Angeles began to form new towns or join preexisting ones. However, some areas, like Avocado Heights, resisted largely due to fiscal reasons. Thus, the community formed without distinction, physical uniqueness, and political governance. As the Los Angeles Times contended, Avocado Heights was “a suburban enigma.”

Alex Trujo and an Andalusian horse dance in Charro tradition through Avocado Heights, 6 September 2017.

Alex Trujo and an Andalusian horse dance in Charro tradition through Avocado Heights, 6 September 2017.

© 2023 Southern California News Group / Pasadena Star-News. Photo by Sarah Reingewirtz.

Click here to view the source. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This enigma found its answer in the 1970s with Latine equestrianism. Residents kept chickens, tended to small plots of farmland, and brought with them their charrería, an equestrian style that includes rope tricks, astute horse maneuvering, and livestock handling. Locals created an equestrian council, which in 1979 supported the construction of a horse arena in the local park. In 1991, the council pushed for the designation as an official equestrian district, increasing the number of horses allowed and enabling residents to stable horses on smaller lots, a minimum of 930 square meters instead of the 1400 square meters required in other unincorporated communities. Those still unable to meet these relaxed zoning requirements stabled their horses in Latine-owned ranches like Ranchos Los Dorados and Sunset View Ranch. In addition, some sidewalks were transformed into sand tracks to accommodate the hooved transport.

The designation of Avocado Heights as an official equestrian district was coupled with a county plan to construct a major horse trail through the suburb’s streets. However, the project was postponed and only reintroduced in 2017. That year, county officials and volunteers counted the number of horses, bicycles, and pedestrians to determine if creating the trail, additional crosswalks, bike lanes, and safer intersections would cut down on the level of car usage. After data was collected, the county public works department allocated US$4.7 million to the project. However, some residents feared it would lead to increased car congestion and health hazards from manure while also bringing horse riders from outside the area. The project has yet to be approved.

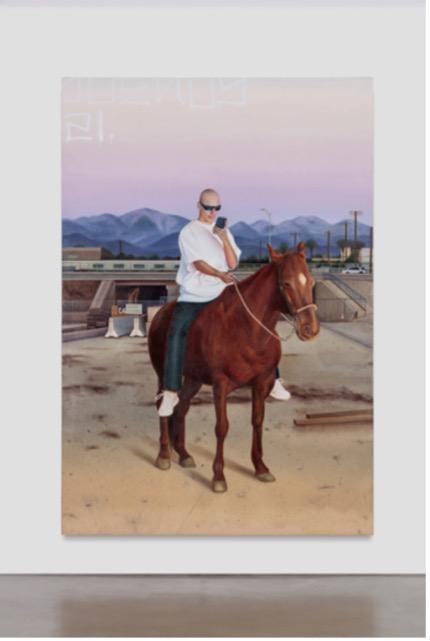

Sueños (Dreams), painting by Joshua White that depicts a man clad in a white T-shirt, denim pants, and Locs sunglasses looking down at a smartphone while sitting astride a horse in a dusty riverbed. The painting was part of the group exhibition “Shatter Glass.”

Sueños (Dreams), painting by Joshua White that depicts a man clad in a white T-shirt, denim pants, and Locs sunglasses looking down at a smartphone while sitting astride a horse in a dusty riverbed. The painting was part of the group exhibition “Shatter Glass.”

© 2022 Joshua White. Courtesy of Alfonso Gonzalez Jr. and Jeffery Deitch Gallery. Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The streets and cultural life of Avocado Heights are filled with its charrería. Riders on the streets show off their skills by performing tricks and dancing with their horses, filling the community’s soundscape. As one resident explained to the San Gabriel Valley Tribune in 2017, “I like to dance my horse on the street. . . . They can hear the noise, and I can hear too, and correct [the horse].” Local riders highlight these skills at social events, joining equestrian clubs like the Charros la Alteña and Charros de la Puente that take part in parades and shows across Southern California. Through these kinds of equestrian social events, the horse riders of Avocado Heights engage in the broader culture of charrería found in the San Gabriel Valley.

This equestrian suburb has also been depicted on canvas. Local artist Alfonso Gonzalez Jr. illustrates aspects of Chicano culture and experiences in the San Gabriel Valley. His painting Sueños (Dreams) shows a man in a white T-shirt, denim pants, and sunglasses looking down at a smartphone while sitting astride a horse on a dusty riverbed. The suburban setting, Chicano fashion, and the horse mark this painting as a totem of the unique cultural landscape of Avocado Heights. Gonzalez’s depiction of the community’s Chicano residents is reminiscent of the historical use of equestrian portraits to aggrandize monarchs and generals. “When thinking about art history and portraiture of people and horses,” the artist explains, “it’s all white men of power, like colonizers.” By replacing the colonizer with the Chicano, Gonzalez asserts the latter in a traditionally colonized, white suburban space.

The Charro identity of Avocado Heights also became the foundation for a local environmentalist movement in opposition to the Quemetco lead-smelting facility established in 1959. That facility has been repeatedly found in violation of state and federal environmental regulations since the 1980s: a rapid gas expansion incident in 1985 led to an employee’s death, a roof failure temporarily halted operations in 2006, and a fire in 2008 forced over 100 workers to evacuate. Galvanized by these chronic problems, an equestrian environmentalist group called the Avocado Heights vaqueros (cowboys) took a stand. With help from locals and other organizations, the Avocado Heights vaqueros have marched and brought awareness to their environmental struggles.

How to cite

Amador, Fernando. “The Equestrian Suburb of Latine Los Angeles.” Environment & Society Portal,

Arcadia (Spring 2023), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9561.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2023 Fernando Amador

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Barraclough, Laura R. Charros: How Mexican Cowboys Are Remapping Race and American Identity. Oakland: University of California Press, 2019.

- Davis, Mike. Magical Urbanism: Latinos Reinvent the U.S. Big City. London: Verso, 2000.

- Sandoval-Strausz, A. K. Barrio America: How Latino Immigrants Saved the American City. New York: Basic Books, 2019.

- Brantz, Dorothee, ed. Beastly Natures: Animals, Humans, and the Study of History. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 2010.

- Valle, Victor M., and Rodolfo D. Torres. Latino Metropolis. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

- Sands, Kathleen Mullen. Charrería Mexicana: An Equestrian Folk Tradition. Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1993.

- Cheng, Wendy. “The Changs Next Door to the Diazes: Suburban Racial Formation in Los Angeles’s San Gabriel Valley.” Journal of Urban History 39, no. 1 (2013): 15–35. doi:10.1177/0096144212463548.