The Portuguese section of the Environmental Justice Atlas (EJAtlas) features a selection of environmental conflicts in Portugal after the democratic revolution of 1974, and the Alviela River pollution is one of them. The EJAtlas is a map of environmental conflicts in the world, set up and managed by Environmental Justice Organizations, Liabilities, and Trade (EJOLT), a program supported by the European Commission. Subsequently, the exploratory project Portugal: Ambiente em Movimento (Portugal: Environment on the Move) took this work further and built a website showcasing 60 conflicts in Portugal, including the Alviela River case. The Alviela River rises in the Serra de Aire e Candeeiros mountain range, extending for 51 kilometers and flowing into the right bank of the Tejo River, near the Figueira Valley in Central Portugal.

In 1957, during the conservative dictatorship in Portugal, which lasted from 1926 to 1974, a local man named Joaquim Duarte organized a petition denouncing the pollution of the Alviela River and sent it to the president of the Ministers’ Council, António de Oliveira Salazar himself. This act marked the birth of the “Alviela Anti-Pollution Commission” (CLAPA).

A public action promoted by CLAPA (Comissão de Luta Anti-poluição do Alviela)

A public action promoted by CLAPA (Comissão de Luta Anti-poluição do Alviela)

This is an undated document found at the Archives of CLAPA and the Junta de Freguesia de Pernes. The use was authorized by the Junta de Freguesia de Pernes (Pernes Town Council).

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

In the 1950s, effluents from tanneries had started to affect local flourmills and olive oil mills, as well as fishing and sand extraction, natural resources closely associated with the riverside villages’ livelihoods. These effluents were mainly solid waste, until, in the 1970s, the use of chromium salts worsened the pollution (Cautela 1977). In 1970, the same Joaquim Duarte took water samples to the National Assembly arguing they should be analyzed. The press took an interest and local inhabitants became increasingly attentive to signs of river pollution in the Alviela River.

Soon after the democratic revolution, in 1974, CLAPA met with the State Subsecretary for the Environment, the Alcanena town council, and the association of tannery industries. They agreed to evaluate the situation, and, in 1979, the government built a wastewater treatment plant in Alcanena; due to funding restraints the construction was only finished in 1988. However, the problem of pollution in the Alviela River was still far from resolved. The plant did not have the capacity to cope with the actual waste produced by the tanneries, and showed signs of maintenance problems. Moreover, local authorities and inhabitants declared that its technology was inadequate and obsolete.

External video. Link https://www.youtube.com/embed/n5CUPSKNVPY.

This video (in Portuguese) shows a clip from TV4Ribatejo, in which a fisherman and boat builder is interviewed. The Alviela River flows into the Tejo River and was once one of Lisbon’s major water sources. In 2009, when the video was shot, it was one of the most polluted rivers in Portugal. The fisherman claimed he did not catch a single fish for a whole year, and not even frogs could be seen in the river. The persistence of sources of pollution and the problems of the ETAR built in Alcanena was not able to prevent the continuous death of fish in the river

Indeed, a decade later, in 2004, the president of Vaqueiros parish reported the appearance of dead fish in the river and demanded that the national water authority and the Alcanena town council take a stand. Following evidence of continuous serious pollution, local inhabitants mobilized once more. In 2005, following an appeal by CLAPA, hundreds of people walked from Pernes to the source of the river in protest. In 2006, 40 entities (municipalities and parishes that bordered the river, parliamentary representatives, and NGOs) created the Commission for the Defense of the Alviela River. The latter committed to carrying out a detailed survey of the river’s environmental conditions, and demanded funds for developing diagnostic studies and solutions to the problem. That year, more than 10,000 citizens signed a petition by the Commission for the Defense of the Alviela River asking parliament to commit to the rehabilitation of the river.

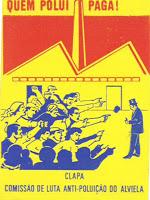

Poster from CLAPA (Comissão de Luta Anti-poluição do Alviela). On the top of the poster we see a sentence in Portuguese: “Those who pollute pay!”

Poster from CLAPA (Comissão de Luta Anti-poluição do Alviela). On the top of the poster we see a sentence in Portuguese: “Those who pollute pay!”

This is an undated document found at the Archives of the CLAPA and the Junta de Freguesia de Pernes. The use was authorized by the Junta de Freguesia de Pernes (Pernes Town Council).

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Two years later, the town council of Santarém promoted a multidisciplinary study on the rehabilitation of the Alviela ecosystem, which was conducted by the company Hidroprojecto. The authors confirmed that the main causes of pollution were the tanneries in Alcanena and cattle farming in Santarém. They proposed to create a coalition of producers, industries, and municipalities, to carry out the integrated treatment of effluents, the monitoring of the river, and its rehabilitation.

In 2009, the national water authority, the Alcanena town council, and the users’ association of the wastewater treatment plant agreed to a protocol that involved undertaking concerted actions to improve wastewater treatment. Also in 2009, the municipality of Santarém started a project named SOS Alviela, located in Vaqueiros, to train local inhabitants to identify native species and to report signs of pollution in the Alviela. In 2014, the Portuguese environment agency signed a protocol with the town councils of Alcanena and Santarém to rehabilitate Alcanena’s wastewater treatment system and the Mouchão-Pernes Waterfalls in a seemingly definite solution to the problem. However, despite a commitment to complete construction by 2015, in February 2015 works had yet to start.

The Alviela River tells one of the oldest histories of popular mobilization against pollution in Portugal. However, this history’s final chapters are still to come. Despite 60 years of mobilization by local citizens and several attempts to bring together national and local authorities, as well as industry, to stop pollution and rehabilitate the river, it remains seriously polluted. How long will it be until the river flows clean is a question that remains to be answered.

How to cite

Oliveira Fernandes, Lúcia de, Oriana Rainho Brás, Teresa Bezerra Meira, and Sofia Bento. “Half a Century of Public Participation to Stop Pollution in the Alviela River, from 1957 to Today.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2017), no. 20. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7919.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2017 Lúcia de Oliveira Fernandes, Oriana Rainho Brás, Teresa Bezerra Meira, and Sofia Bento

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Cautela, Afonso. Ecologia e luta de classes em Portugal. Reportagens. Socicultur: Lisboa, 1977.