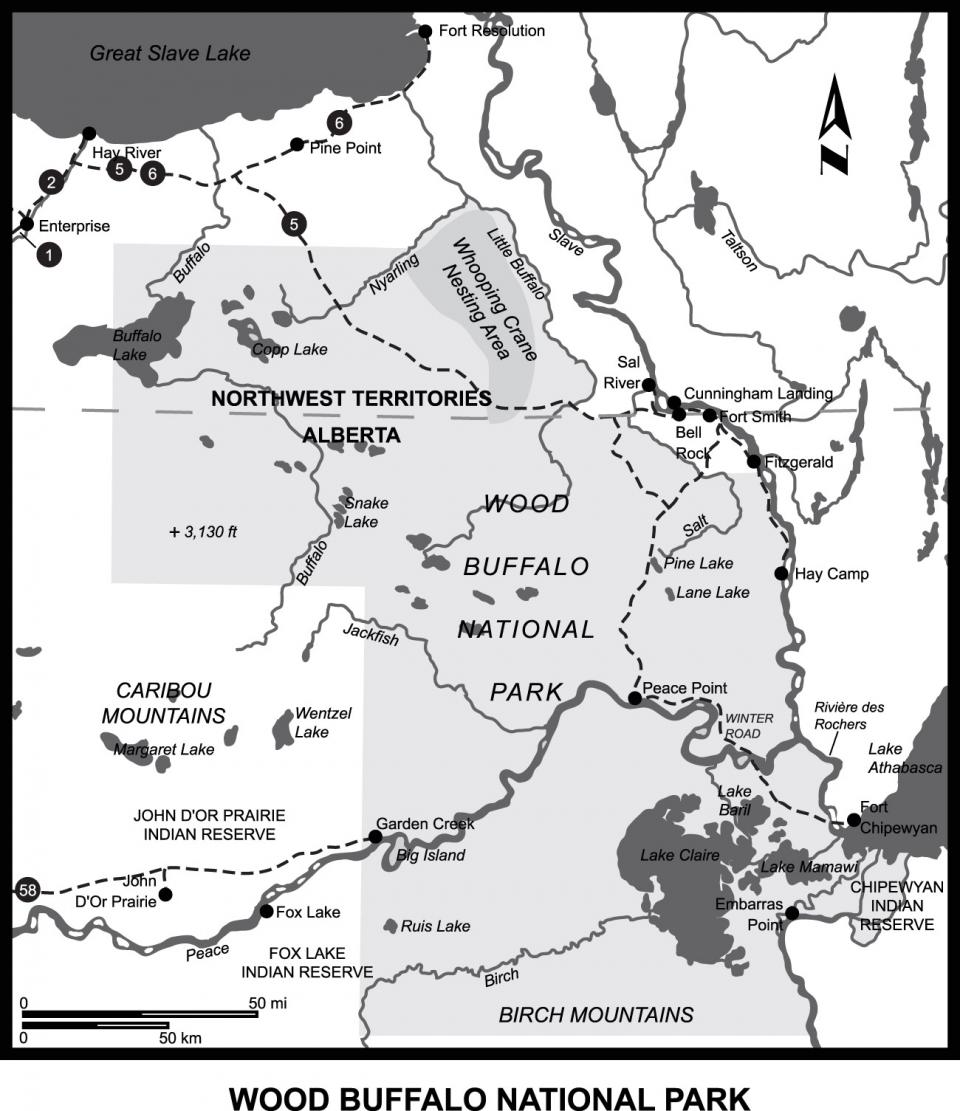

Bison population survey photograph, Wood Buffalo National Park (17 July 1946)

Bison population survey photograph, Wood Buffalo National Park (17 July 1946)

© Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2013.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/C-148456

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

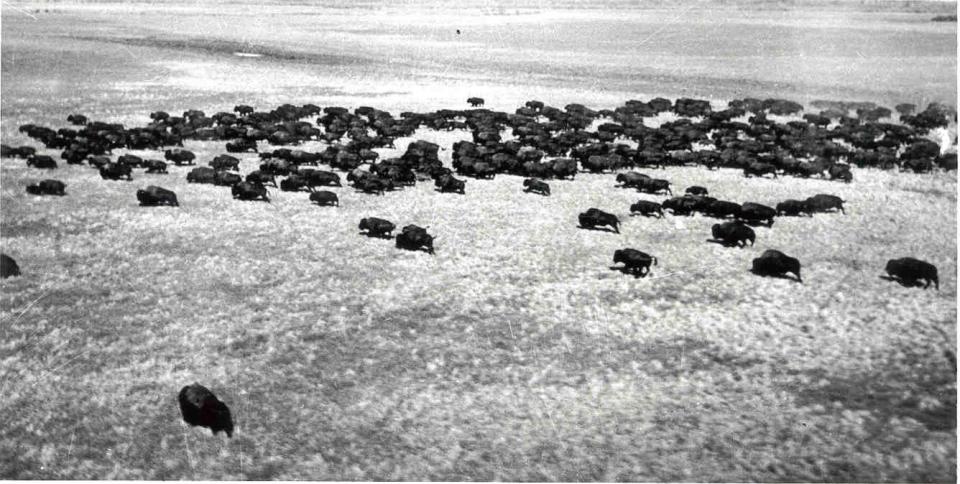

Wood Buffalo National Park claims many distinctions: it is North America’s biggest national park (and the world’s second biggest at 44,807 km² ), a UNESCO World Heritage site, home to the largest free-roaming herd of wood bison, the first federal park in Canada’s territorial north, summer home to the last major migratory flock of whooping cranes, and the largest dark-sky reserve on the planet. These accolades may lend themselves to a popular image of remote wilderness, but the park’s wildlife has also been subject to some of the most intrusive and ill-conceived management interventions in Canadian history.

The Canadian government established the park in 1922 to protect a remnant herd of wood bison (a sub-species of the American plains bison), setting aside a large area of boreal forest plain that straddles the border between the province of Alberta and the Northwest Territories. Preserving the bison did not necessarily mean “hands-off” management, however, as government officials soon hatched a scheme to transport thousands of plains bison from the fenced and overstocked Buffalo National Park (a former park in southern Alberta) to the supposedly understocked range of Wood Buffalo National Park. Zoologists in Canada, the United States, and Britain vigorously and almost unanimously opposed the plan, fearing the loss of the wood bison sub-species to hybridization and the transmission of tuberculosis from the infected herds in southern Alberta. But government officials stubbornly persisted, transporting 6,673 plains bison to Wood Buffalo National Park between 1925 and 1928.

Bulldozing a slaughtered bison toward the Hay Camp abattoir, Wood Buffalo National Park (1952)

Bulldozing a slaughtered bison toward the Hay Camp abattoir, Wood Buffalo National Park (1952)

© Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2013.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/C-148893

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Hunters skin a bison as part of the 1948 slaughter, Wood Buffalo National Park.

Hunters skin a bison as part of the 1948 slaughter, Wood Buffalo National Park.

© Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2013.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/C-148901

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

By the late 1940s the dire consequences zoologists had predicted had mostly come to pass. The plains bison had bred freely with the wood bison and infected them not only with tuberculosis but also brucellosis (a disease causing intense fevers and miscarriages among pregnant females). Federal wildlife officials attempted to manage their way out of past mistakes, conducting annual round-ups and testing of bison so as to slaughter diseased animals. To provide revenue for the program, the government sold salvageable bison meat to northern trading companies and, increasingly, to meat packers, hotels, and restaurants in southern Canada. Between 1951 and 1967, wildlife managers killed four thousand park bison and distributed nearly two million pounds of meat. Periodically, the goals of disease control and commercial development came into conflict, particularly when the federal government’s northern administration began to actively promote bison meat as part of a much broader program of economic development in the region.

Bison meat ready for shipping from Hay Camp, Wood Buffalo National Park (1952)

Bison meat ready for shipping from Hay Camp, Wood Buffalo National Park (1952)

© Government of Canada. Reproduced with the permission of the Minister of Public Works and Government Services Canada 2013.

Source: Library and Archives Canada/C-148897

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Management controversies did not end with the cessation of meat production. In the 1970s the government held roundups to inoculate against spontaneous anthrax outbreaks among bison herds, a practice that led to high herd mortality and criticism from local Aboriginal communities. In the 1980s federal wildlife managers proposed the complete eradication of bison from the park so as to reintroduce disease-free herds after a period of ten years. An environmental assessment of this plan revealed intense opposition from local Aboriginal groups, the Canadian public, and even within the government, forcing the mass slaughter proposal to be abandoned. But if the bison of Wood Buffalo National Park were no longer subject to eradication, neither had they been preserved in anything remotely resembling an untouched state. Subject to intensive management, infection, and hybridization, the wood bison remind us that the fingerprints of human intervention work their way deeply into even the most remote wilderness national parks.

How to cite

Sandlos, John. “Northern Bison Sanctuary or Big Ranch? Wood Buffalo National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2013), no. 19. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5651.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2013 John Sandlos

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Brower, Jennifer. Lost Tracks: Buffalo National Park, 1909–1939. Edmonton: Athabasca University Press, 2008.

- Carbyn, Ludwig N., Sebastian Oosenbrug, and D. W. Anions. Wolves, Bison, and the Dynamics Related to the Peace-Athabasca Delta in Canada's Wood Buffalo National Park, Edmonton. Alberta: Canadian Circumpolar Institute, 1993.

- Carbyn, Ludwig N., Nicholas J. Lunn, and Kevin Timoney. “Trends in the Distribution and Abundance of Bison in Wood Buffalo National Park.” Wildlife Society Bulletin 26, no. 3 (1998): 463–70.

- Ferguson, Theresa, A., and Clayton Burke. “Aboriginal Communities and the Northern Buffalo Controversy.” In Buffalo, edited by John Foster, Dick Harrison and I.S. McLaren, 189–202. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press, 1992.

- Foster, Janet. Working for Wildife: The Beginnings of Preservation in Canada. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1998.

- Loo, Tina. States of Nature: Conserving Canada's Wildlife in the Twentieth Century. Vancouver: UBC Press, 2011.

- Sandlos, John. Hunters at the Margin: Native People and Wildlife Conservation in the Northwest Territories. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 2007.