At 7:54 p.m. on 14 October 1940, the church of St. James’s Piccadilly, in the heart of London, was hit by high explosive and incendiary bombs. By the next morning, this exquisite late seventeenth-century place of worship, designed by Sir Christopher Wren of St. Paul’s Cathedral fame, was reduced to a roofless shell, open to the elements. A temporary ceiling was erected over part of the south isle in 1941 to allow services to resume, but it was nearly seven years before the church was rebuilt.

St. James’s Piccadilly after the church had been bombed during the Blitz on 14 October 1940.

St. James’s Piccadilly after the church had been bombed during the Blitz on 14 October 1940.

Unknown photographer, 1940.

Courtesy of St. James’s Church Piccadilly.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Meanwhile, other worshippers had moved in: worshippers of sunshine and rainfall, creatures who like to sink their roots into living soil. Having germinated in the ruins without human intervention, they were regarded as “weeds.” A botanist, Professor E. Salisbury, nonetheless took the trouble to catalogue them, and found that there were forty-two species in all, mainly common wildflowers and grasses, but also some exotics that had escaped from Kew Gardens after it too was bombed, along with tomato plants, whose seeds were possibly dropped by birds.

Eighty years later, in the midst of another kind of disaster, one manifesting in viral spread rather than dropping bombs, a creative trio at St. James’s drew inspiration from these hardy blow-ins to develop a collaborative project called “Aftermath: Weeds and Wilding.” It launched on Palm Sunday 2021, when seeds of several of the species that had found a foothold in the ruins were sown in a “Bomb Box.” Subsequently, Harbinger tomato seedlings were planted along the street railings, and parishioners too were encouraged to get involved in both practical and creative ways.

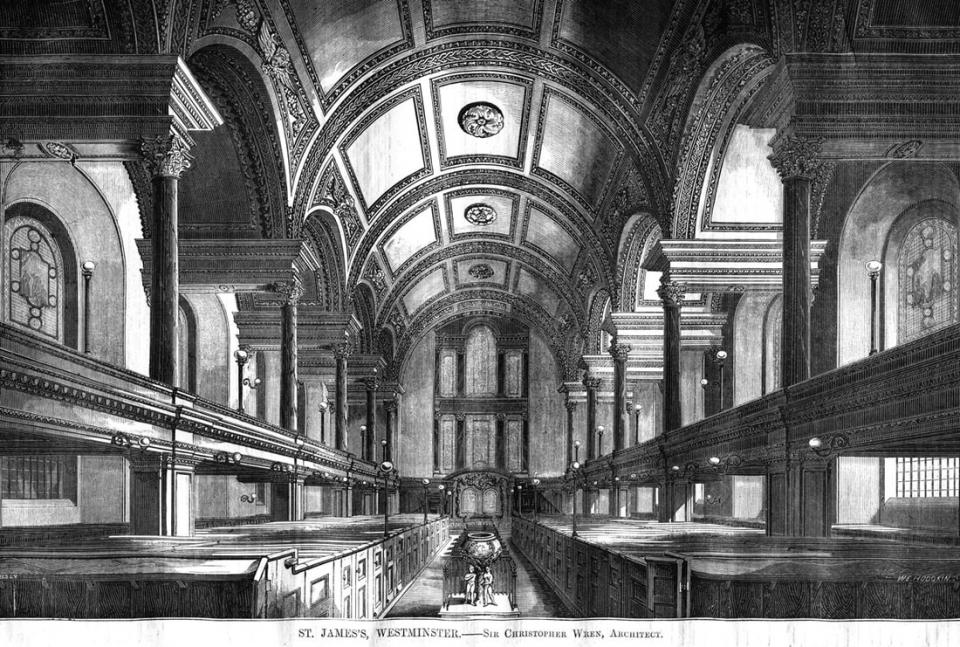

An 1857 print from The Builder of St. James’s Westminster—Sir Christopher Wren, Architect.

An 1857 print from The Builder of St. James’s Westminster—Sir Christopher Wren, Architect.

Unknown artist, n.d.

Courtesy of St. James’s Church Piccadilly

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In 2018, St James’s received a Gold Eco Church Award from the ecumenical Christian conservation organization, A Rocha. To receive this recognition, churches must demonstrate outstanding environmental achievement across five aspects of their operation: incorporating care for the earth within worship and teaching; minimizing the carbon footprint and other environmental impacts of buildings and operations; organizing and participating in community and global environmental engagement; encouraging a more sustainable lifestyle; and managing church land for conservation, recreation, and contemplation.

Plants growing in St. James’s Piccadilly’s Bomb Box in September 2021.

Plants growing in St. James’s Piccadilly’s Bomb Box in September 2021.

Photograph by Deborah Colvin, 2021.

Click here to view source.

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

St James’s Southwood Garden, an oasis of green in the concrete jungle of Central London, is burgeoning with biodiverse life, especially of the plant and insect variety, and in the microbial-rich soil, to which the gardener Catherine Tidnam devotes especial care. Her planting scheme ensures that there is food for an array of pollinators all year round. There is an assortment of mini habitats—piles of leaves, wood stacks, mini bogs—and the garden is frequented by two kinds of bat, and a variety of birds. The garden received a Green Flag Award in 2017, which has been re-awarded each year, and the church, which sits on a recognized “Bee line” for pollinators, contributes to the Wild West End initiative to develop biodiversity corridors through the city.

The Aftermath project takes this bio-inclusive praxis of creation care to a whole new level. Led by agricultural scientist and churchwarden, Deborah Colvin, together with artist Sara Mark and poet Diane Pacitti, this undertaking intertwines the church’s triple heritage of faith, science, and the arts. In its neoclassical design and the ebullient natural imagery of its Grinling Gibbons altarpiece, the church is an architectural embodiment of the natural theology of the scientific enlightenment, according to which the empirical investigation of Nature yields insight into its divine Creator. Yet, adjacent to the side entrance, it also bears a memorial to the “artist-poet-visionary” William Blake, who was baptized there on 11 December 1757, in a Grinling Gibbons font. Scientifically informed and faith-inspired, Aftermath also embraces this Romantic inheritance of prophetic social critique, environmental protest, and creative imagination. As the seeds sprouted in the Bomb Box, other plants popped up between the paving stones, the tomatoes ripened, and poetry, artwork, and ecological reflections proliferated on the website, while the community gathered, in person and online, to participate in this celebration of weeds and wilding.

St. James’s Church Piccadilly in 2013.

St. James’s Church Piccadilly in 2013.

Photograph by Zeisterre, 2013.

Accessed via Wikipedia on 24 January 2022. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In keeping with St. James’s social justice ministry, which includes supporting asylum seekers and providing food and shelter for people experiencing homelessness, Aftermath puts pressure on the whole concept of the “weed” and seeks to counter the marginalization and scapegoating of the “alien” and “queer.” Recalling that among the church’s former parishioners. at different times, were slave owners, such as the Duke of Buckingham, and the former slaves and abolitionists, Ottabah Cugoano and Olaudah Equiano, Diane Pacitti observes in her Rogation Walk report that “many of the people who embodied the seeds of change in their time were hidden, ignored or actively persecuted. In fact, they were treated in the same way as we treat weeds.”

Celebrating the resilience and regenerative capacities manifest in the prolific and resourceful plants that flourished in the midst of disaster, Aftermath is premised on an ecotheological understanding of nature as a “communion of subjects,” as Thomas Berry puts it, rather than a collection of objects. It is also inspired by the deeply ethical relationship with plants cultivated by those, such as the Potawatomi forbears of Robin Wall Kimmerer, who were themselves treated like weeds by European colonizers. Located in the double horizon of mass species extinction and intolerance of human “outsiders,” this project exemplifies the praxis of sympoiesis recommended by Donna Haraway in an article on “making kin”: collaborating with more-than-human others “to reconstitute refuges, to make possible partial and robust biological-cultural-political-technological recuperation and recomposition” in the midst of our own troubled times.

How to cite

Rigby, Kate. “In Praise of Weeds: Sympoiesis at St. James’s Piccadilly.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2022), no. 1. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9382.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2022 Kate Rigby

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Berry, Thomas. Evening Thoughts: Reflecting on Earth as Sacred Community. Edited by Mary Evelyn Tucker. San Francisco: Sierra Club, 2006.

- Haraway, Donna. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6, no. 2 (2015): 159–165.

- Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge and the Teaching of Plants. Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013.

- Leopold, Aldo. “What is a Weed?” In The River of the Mother of God and other Essays by Aldo Leopold, edited by Susan L. Flader and J. Baird Callicott, 306–309. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1991.

- Marris, Emma. Rambunctious Garden: Saving Nature in a Post-Wild World. New York: Bloomsbury, 2013.

- Pope Francis. Laudato si': On Care for our Common Home. Encyclical Letter. Rome: Vatican Documents, 2015.

- Rigby, Kate. “Religion and Ecology: Towards a Communion of Creatures.” In Environmental Humanities: Voices from the Anthropocene, edited by Serenella Iovino and Serpil Oppermann, 273–94. London: Rowman and Littlefield, 2016.