Townsville is a city proud of its abilities to handle extremes. Located in Australia’s dry tropics, Townsville depends on seasonal monsoons (often including cyclones) to maintain its water supply. The way Townsville responds to major weather events has become part of its collective identity. In Townsville, however, community acceptance of recurrent but unpredictable major weather events has not led to the development of a sustainable flood memory. Two recent floods, in 1998 and 2019, demonstrate that although Townsville often experiences heavy rains, it has failed to foster a communal memory and understanding of how to live with flooding.

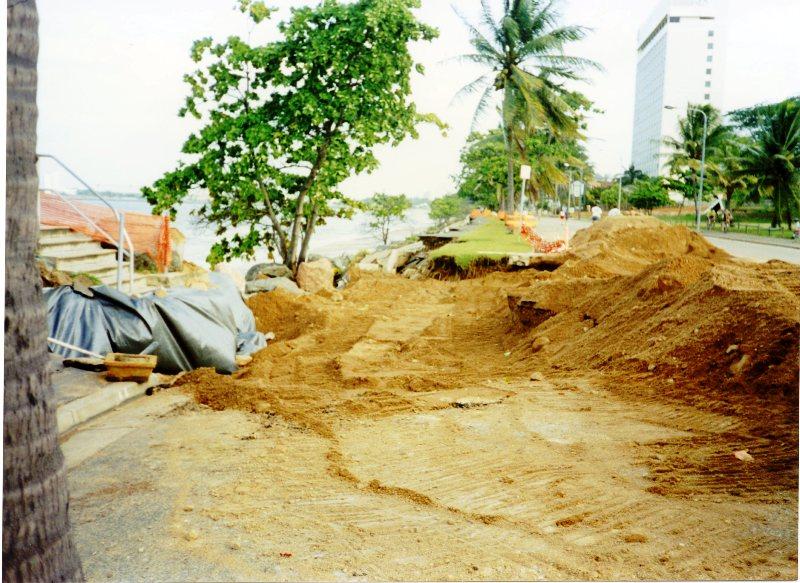

Photograph showing damage to Townsville’s Strand, 15 January 1998.

Photograph showing damage to Townsville’s Strand, 15 January 1998.

Unknown photographer, 15 January 1998.

Courtesy of CityLibraries Townsville, Local History Collection.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In January and February 2019, Townsville received more than 1,400 millimeters of rain, causing flash and riverine flooding that resulted in the deaths of four people and the inundation of several thousand homes and businesses. When reporting this event, media outlets frequently compared it to another Townsville flood, the “Night of Noah.” Despite the commonality of flooding in Townsville, floods do not sit comfortably within Townsville’s collective “disaster identity.” Understanding of flooding in the city is poor, and its possible depths and intensities are not well recognized. Positioning the Night of Noah as “exceptional” inhibited the learning that disasters and memory can bring.

The Night of Noah occurred on 10 January 1998, when Townsville experienced its wettest ever 24-hour period, recording 549 millimeters of rain. The event was associated with Ex-Tropical Cyclone Sid, which had already caused flooding north of Townsville. The city became a river as blocked and narrow drains failed to evacuate the heavy rains effectively. The damage was significant: one man lost his life, up to one hundred residences were inundated, and Townsville’s satellite communities of Black River and Bluewater sustained extensive damage, including the washing away of eight homes. Townsville’s foreshore, known as the Strand, was badly eroded, and on Magnetic Island (a short ferry ride from Townsville) a landslide caused major damage to a resort complex. Yet despite the damage that had already been caused by Ex-Tropical Cyclone Sid, the Night of Noah was not predicted.

Photograph of damage to Townsville’s Strand from heavy rain, January 1998.

Photograph of damage to Townsville’s Strand from heavy rain, January 1998.

Unknown photographer, 1998.

Courtesy of CityLibraries Townsville, Local History Collection.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

A local radio personality named the event the Night of Noah because no one expected it, just like “no one expected Noah.” Local media coverage emphasized the size of the event and the community’s ability to respond. Local newspaper the Townsville Bulletin provided a special pull-out supplement and North Queensland Ten News produced a one-hour television documentary called The Flood: January ’98. As explained by a meteorologist in The Flood, extreme events “are very hard to forecast because of their nature, because they’re so unusual, and because they develop … it develops right over you. It just happens.” A perception grew that the city was lucky to have avoided a greater disaster.

In the years following the Night of Noah, the Bulletin began to historicize the event. Subsequent accounts highlighted the extent of the devastation, noted the heroism of responders, and emphasized light-hearted anecdotes from those caught by the floodwaters. Meanwhile, measures were taken by the city’s council; specifically, the city turned to tackling issues relating to storm surges and cyclones. It upgraded urban flood-mitigation systems by addressing issues around storm drainage, conducted flood studies, and introduced requirements for new housing developments. According to a 2009 risk management study of Townsville, floods were relegated to an “inconvenience rather than [a] disaster” and the notion that Townsville was vulnerable to major flooding was considered “unlikely.” Despite acknowledging it as a possibility, significant riverine flooding of the Ross River was not considered in detail.

Photograph of Belgian Gardens cemetery, Townsville, during the January 1998 flood.

Photograph of Belgian Gardens cemetery, Townsville, during the January 1998 flood.

Unknown photographer, 1998.

Courtesy of CityLibraries Townsville, Local History Collection.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

During the flooding of 2019, memories of the Night of Noah had a prominent place in local media reports. Initially, during the first days of rain, media outlets used the Night of Noah as a high-water mark. As the rain continued and dam water was released, the 2019 floods eclipsed the Night of Noah and the city moved into uncharted waters. Social-media users shared maps showing likely areas of devastation and videos of the flooding, and those with boats aided in evacuations. Active flood memories and lay knowledge were created and spread as the disaster unfolded.

A flooded Townsville street in 2019.

A flooded Townsville street in 2019.

Photograph by Rohan Lloyd, 2019.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

In the end thousands of homes were inundated, many of them in areas known to be prone to flooding. As the waters receded the local community attempted to explain the damage that had occurred. They criticized the local council’s management of dam releases and the inability to secure flood insurance, and found the notion of 1-in-500-year events inexplicable and unhelpful. Tellingly, those who attempted to remain in their homes but had to be rescued as the waters rose suggested that they were prepared for cyclones and storm surges but had no evacuation plans for a “sustained flooding event.”

Scott McKinnon argued that the 1974 Brisbane floods became a reference point for long-term residents of Brisbane but the floods were also “securely located in the past.” I think the same can be said of the Night of Noah. The exceptionalism of the Night of Noah made it difficult to latch on to as a pillar of the city’s collective identity. Large floods were not something that residents needed to prepare for because they were so unlikely. Yet, if Noah was a 1-in-100-year event and 2019 a 1-in-500-year event, it is likely that “unprecedented” disasters are part of Townsville’s climate. The city needs to accept and begin communicating this understanding as part of living with flooding.

How to cite

Lloyd, Rohan. “Remembering the Night of Noah: Flood Memory and Townsville’s Floods of 1998 and 2019.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. 4. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9002.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Rohan Lloyd

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- McEwen, Lindsey, Joanne Garde-Hansen, Andrew Holmes, Owain Jones, and Franz Krause. “Sustainable Flood Memories, Lay Knowledges and the Development of Community Resilience to Future Flood Risk.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42 (2017): 14–28.

- Garde-Hansen, Joanne, Lindsey McEwen, Andrew Holmes, and Owain Jones. “Sustainable Flood Memory: Remembering as Resilience.” Memory Studies 10, no. 4 (2017): 384–405.

- Margaret Cook. “‘It Will Never Happen Again’: The Myth of Flood Immunity in Brisbane.” Journal of Australian Studies 42, no. 3 (2018): 328–42.

- Bohensky, Erin L., and Anne M. Leitch. “Framing the Flood: A Media Analysis of the Themes of Resilience in the 2011 Brisbane Flood.” Regional Environmental Change 14, no. 2 (2014): 475–88.

- Townsville City Council. “Townsville City Natural Disaster Risk Management Study Stage 1: Draft Final Report.” The Institute for International Development, Adelaide, 2009.

- McKinnon, Scott. “Remembering and Forgetting 1974: The 2011 Brisbane Floods and Memories of an Earlier Disaster.” Geographical Research 57, no. 2, (2019): 204–14.