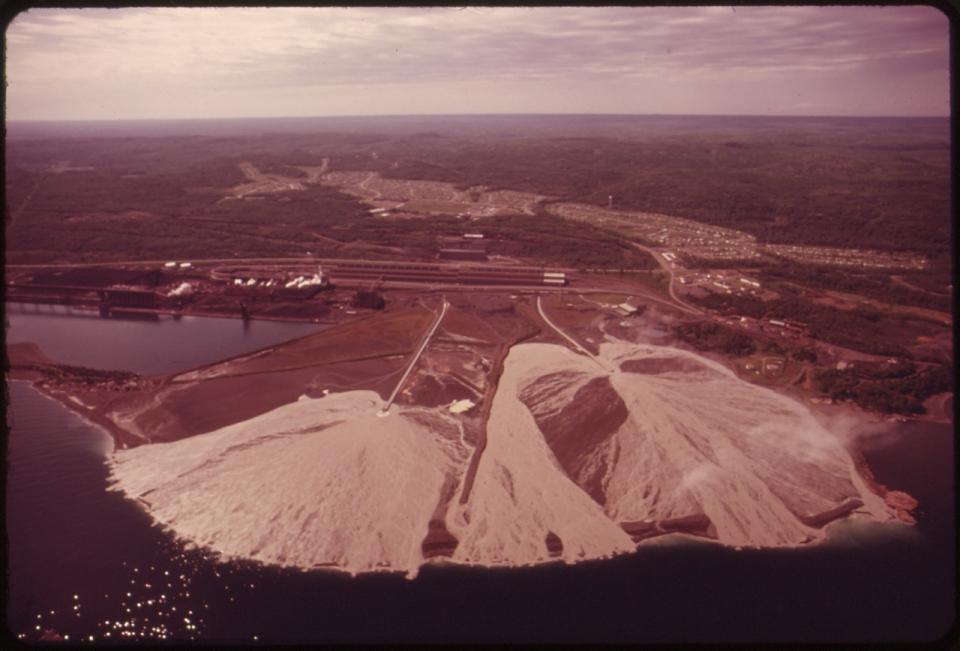

In 1955, the Reserve Mining Company began operating in Silver Bay, Minnesota. The processing plant for Reserve’s taconite mine was situated right off the shore of Lake Superior, but in the 25 years that the company was operating, the distance between the processing plant and water’s edge slowly grew. A vast delta had been created by the accumulation of the fine waste-rock that Reserve was discharging into Lake Superior. Their processing plant crushed taconite rocks to allow for the extraction of iron they contained, but two-thirds of the taconite were discharged in the form of tailings. By 1980, the delta had grown to such a degree that the processing plant was over one-third of a mile from the edge of Lake Superior.

The slowly expanding tailings delta in Silver Bay, MN.

The slowly expanding tailings delta in Silver Bay, MN.

Donald Emmerich/EPA 1973

Original title: “TACONITE TAILINGS FROM RESERVE MINING AT SILVER BAY ARE DISCHARGED INTO LAKE SUPERIOR, 06/1973 “

Series: DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency’s Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972 - 1977

Click here to view National Archives source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

When the plant first began operating, few questioned the discharging of materials into Lake Superior. Silver Bay was a mining town and the majority of its citizens relied on Reserve as their primary source of income. But by the late 1960s, residents and local sportfishing groups were detecting changes in the water. Their efforts to get the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency involved got the attention of the Environmental Protection Agency, who intervened and took Reserve to court in 1973.

This trial put the community of Silver Bay at odds. Reserve’s operations were tied to the livelihood of many in the community, but at the same time, the polluted water of Lake Superior posed an invisible threat to the lives of everyone. Results from federally-funded scientific studies revealed the damage the tailings discharge had caused: fish populations were harmed by the increase in water turbidity, while the presence of fibrous minerals—described in research findings as “asbestos-like” and thought to be carcinogenic—were detected by EPA chemists. Soon, the town’s struggle for economic well-being was squaring off with the town’s struggle for public health.

Reserve’s trial lasted over a year, with appeals from Reserve keeping the case open until 1980 when they developed holding ponds for the tailings. The EPA and concerned citizens won out in a landmark case, which established regulations on industrial pollution. Reserve continued to operate for a few years before shutting their doors. Another company—NorthShore Mining—picked up where they left off, and they continue to utilize holding ponds to prevent tailings from entering the lake.

Taconite tailings from Reserve Mining Company are discharged via a chute into Lake Superior.

Taconite tailings from Reserve Mining Company are discharged via a chute into Lake Superior.

Donald Emmerich/EPA 1973

Original title: “RESERVE MINING COMPANY’S TACONITE PLANT IN SILVER BAY. NORTH CONVEYOR CHUTE DISCHARGES TACONITE TAILINGS INTO LAKE SUPERIOR.”

Series: DOCUMERICA: The Environmental Protection Agency’s Program to Photographically Document Subjects of Environmental Concern, 1972 - 1977

Click here to view National Archives source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Reserve’s pollution cannot be undone; the tailings dispersed in Lake Superior are irremovable. Decades after Reserve’s trial, the delta remains—but it is different now. Plants have begun to grow, slowly turning the delta to soil. Local youth plant pine trees, turning this once unnatural space into a landscape that is part of the community. Embedded in the layers of the delta is the history of Silver Bay’s mining conflict: the struggle of a torn community, the legal battle, and the invisible health hazards that came with Reserve’s pollution. The long-term impact of the taconite tailings is still debated, but the presence of the delta is not. It is here to stay, a landmark of Silver Bay’s history.

How to cite

Schuchhardt, Caitlyn. “Taconite Mining in Silver Bay: A Tale of Extraction and Accumulation.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2015), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/6863.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2015 Caitlyn Schuchhardt

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Hemphill, Stephanie. “Legacy of the Reserve Mining Case.” Minnesota Public Radio, October 29, 2003. Source: http://news.minnesota.publicradio.org/features/2003/09/29_hemphills_reservehistory/

- Huffman, Thomas. “Exploring the Legacy of Reserve Mining: What Does the Longest Environmental Trial in History Tell Us About the Meaning of American Environmentalism?” Journal of Policy History 12.3 (2000): 339-368.

- Huffman, Thomas. “Enemies of the People: Asbestos and the Reserve Mining Trial.” Minnesota History, Fall 2005.

- Minnesota State Historical Society. "United States of America v. Reserve Mining Company.” Source: http://www.mnopedia.org/event/united-states-america-v-reserve-mining-company