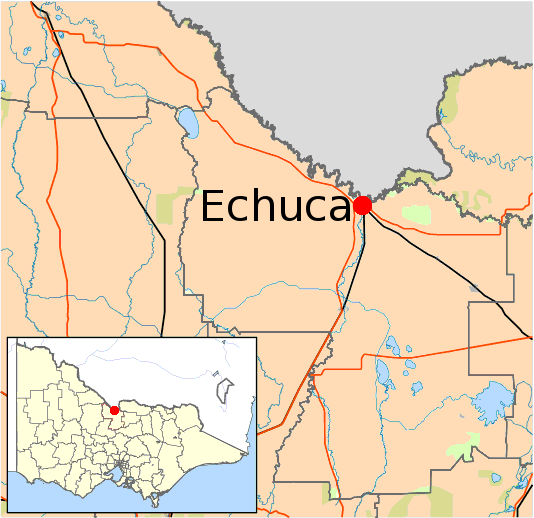

Map showing the location of Echuca, within the Australian state of Victoria.

Map showing the location of Echuca, within the Australian state of Victoria.

Map by Cassowary & VicMap Lite. Modified by Rebecca Le Get. Click here to view Wikimedia source for the original image.

This work is licensed under the GNU Free Documentation License.

Tuberculosis, formerly known as consumption, is a disease that primarily attacks the lungs and which has long plagued humankind. The British Empire of the late nineteenth century was no exception. After Robert Koch identified the bacterial cause of tuberculosis in 1882, consumptive people were increasingly reviled as carriers of contagion. The territories of the Empire offered various locations for emigration that desperate tuberculous Britons, with the requisite financial means, hoped would offer a permanent cure. The long sea voyages to reach Britain’s overseas dominions were considered therapeutic in and of themselves: passengers could inhale the ocean air during the weeks of sailing. But these ships were also taking their passengers to colonies that were believed to have therapeutically suitable landscapes and climates, including Australia.

But where in Australia would be the most suitable location to cure the tuberculous? While the pure, cold mountain air of the alpine regions appealed to some medical professionals, others believed the cure would be found in the dry, sunny plains of southern mainland Australia. One popular destination for these voyages was the Port of Melbourne, in the Colony of Victoria. However, the metropolis lacked the resources to care for the influx of unwell migrants, and these tuberculous newcomers were feared to be spreading their disease throughout the city. Those who could muster the strength to travel overland often headed north, to the drier and warmer inland areas. One family who did this was the Serjeant family, who arrived in Melbourne in 1888, eventually settling in the river port town of Echuca. In 1889, the Serjeants and a Madame Varley opened a charitable sanatorium in the town that was financed by donation and cared solely for the tuberculous.

Photograph of the Murray River at Echuca, showing the river red gum trees that lined the riverbanks. Ca. 1900–1953.

Photograph of the Murray River at Echuca, showing the river red gum trees that lined the riverbanks. Ca. 1900–1953.

Photograph by Mr. Noark, State Rivers and Water Supply Commision. Courtesy of the State Library Victoria, Australia. Rural Water Corporation Collection.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This institution was founded in direct response to the number of ill people who arrived in Echuca but could not find suitable accommodation. Catering for those who arrived at the Port of Melbourne, a committee based in the city assessed prospective patients for admission. Successful applicants were placed on a waiting list and would be notified by the committee when they should travel to Echuca. A letter by George Serjeant, a physician, in the British Medical Journal (1889) noted:

Any coming from England could be met by Mrs. Varley in Melbourne, who would send them safely here to the hospital, so that friends in England would have no cause for anxiety as to their welfare on landing in Australia.

As noted by Bryder (1996), British anxieties around traveling to a new land in the late nineteenth century often revolved around the fear of being in a location where English was not spoken. In colonial Australia and New Zealand, it was assumed that the majority of people encountered would have an English background. Hence it was an appropriate part of the world for therapeutic emigrants who wanted to experience a change in climate, but not culture.

Photograph of the Victorian Sanatorium for Consumptives building, 1899.

Photograph of the Victorian Sanatorium for Consumptives building, 1899.

Photographer unknown. Courtesy of the Special Collections Reading Room (Monash University).

Image source: Victorian Sanatorium for Consumptives. Tenth annual report of the Victorian Sanatorium for Consumptives, Echuca and Macedon, for the year ending 30th June, 1899. Melbourne: Varley Brothers, 1899.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The climate of Echuca explains the town’s popularity for health seekers. Not only does it have a higher average number of bright sunlight hours per year than most of the United Kingdom, but Echuca is also near the largest river red gum forest on the continent. The river red gum, along with other eucalypt species, was believed to have health benefits for sufferers of tuberculosis. The strong, characteristic scent of gum trees was believed to have antiseptic properties, and hence these forests not only acted as a physical barrier against harmful, dust-laden winds but were also thought to ensure the cleanliness of the town’s air.

This association between Echuca and the hope of improved health continued long after the closure of the sanatorium founded by Varley and the Serjeants. Demand for accommodation and care of the traveling tuberculous continued, much to the consternation of residents. Curiously, the Victorian Municipal Directory, a guide to the local government areas of the Colony—and later State—of Victoria continued to note that Echuca was a location considered to be “beneficial for chest diseases” until 1958, half a century after the first sanatorium had closed. The impact of tuberculosis on the development of the town of Echuca is no longer obvious in the present time. But the importance of Echuca’s sunny plains and flora, in late nineteenth-century understandings of tuberculosis treatment, made it a desirable destination for sufferers of tuberculosis who saw it as a place that could cure them.

How to cite

Le Get, Rebecca. “Tuberculosis in Echuca, and the Therapeutic Migration to Southeastern Australia (1889–1908).” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2018), no. 29. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8477.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 Rebecca Le Get

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Bryder, Linda. “‘A Health Resort for Consumptives’: Tuberculosis and Immigration to New Zealand, 1880–1914.” Medical History 40 (1996): 453–71. doi:10.1017/S002572730006169X.

- Haines, Robin F. “Therapeutic Emigration: Some South Australian and Victorian Experiences.” Journal of Australian Studies 16, no. 33 (1992): 76–90. doi:10.1080/14443059209387101.

- Le Get, Rebecca. “A Home Among the Gum Trees: The Victorian Sanatorium for Consumptives, Echuca and Mount Macedon.” Landscape Research (2018). doi:10.1080/01426397.2018.1439461.

- Serjeant, George. “Consumptives and Long Sea Voyages.” British Medical Journal (15 June 1889): 1388. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.1485.1387.

- Victorian Municipal Directory. Victorian Municipal Directory also Commonwealth and State Guide, and Water Supply Record for 1958. Brunswick: Arnall & Jackson, 1958.