Moving On

Drought ultimately doomed Stearns’s gamble on the shortgrass steppe, and in the spring of 1918 she conveyed her homestead and its punishing mortgage to her son, Emory. Once again transient, she moved west to Great Falls, Montana, where she remarried for a third time, and then followed this husband down to the Texas coast, where, divorced once again, she died in 1931.

Abandoned homestead building of similar construction, located a few townships to the northeast. Photograph by Sara Gregg, 2019.

Abandoned homestead building of similar construction, located a few townships to the northeast. Photograph by Sara Gregg, 2019.

2019 Sara Gregg

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Emory almost immediately fled drought and disaster for California, leaving the homestead’s mortgagors as absentee owners until neighboring ranchers (the Stenslands, who had contested Stearns’s claim in 1914) bought the parcel in the 1950s. Their descendants still own the land today, and families like the Stenslands provide the continuity of community in Valley County. While these “stickers” trace their roots back to the early-twentieth-century land rush, the majority of settler-colonists who tried their luck in Montana, known as “boomers,” drifted off like Lily in search of more reliable pastures.

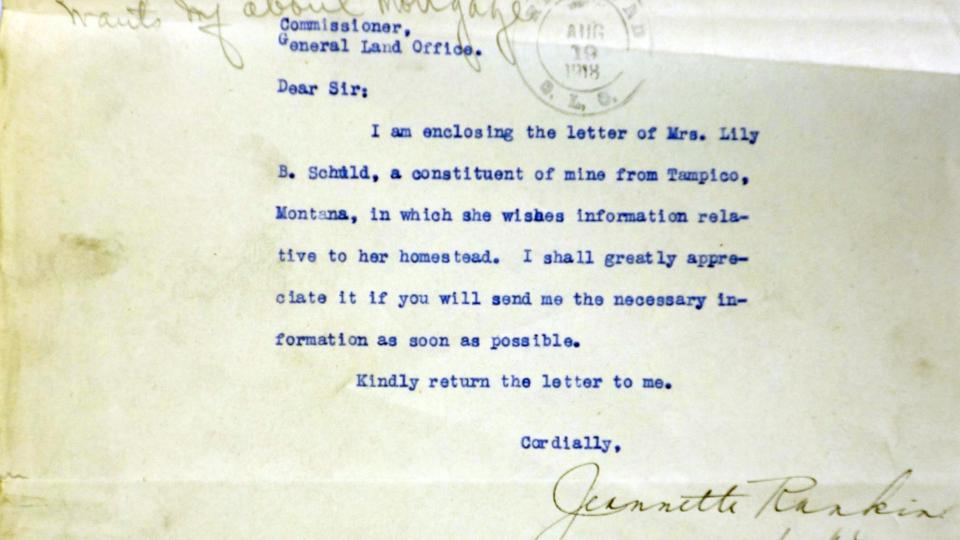

Congresswoman Jeanette Rankin was the first woman elected to the United States House of Representatives, in 1916, and during her first term in office she garnered worldwide renown for her vote in opposition to the U.S. entry into the Great War. The sole Representative to Congress from the State of Montana, she was elected as a Republican. Among Rankin’s other efforts (she was a suffrage organizer, a reformer, and a pacifist) she did the daily work of advocating for her constituents, including Lily Stearns Schuld. This letter to the Commissioner of the General Land Office, dated 17 August 1918, was a typical piece of congressional correspondence with federal agencies, advocating for the interests of a constituent, in this case, Lily Schuld (formerly Stearns) on a question relating to Schuld’s mortgage.

Congresswoman Jeanette Rankin was the first woman elected to the United States House of Representatives, in 1916, and during her first term in office she garnered worldwide renown for her vote in opposition to the U.S. entry into the Great War. The sole Representative to Congress from the State of Montana, she was elected as a Republican. Among Rankin’s other efforts (she was a suffrage organizer, a reformer, and a pacifist) she did the daily work of advocating for her constituents, including Lily Stearns Schuld. This letter to the Commissioner of the General Land Office, dated 17 August 1918, was a typical piece of congressional correspondence with federal agencies, advocating for the interests of a constituent, in this case, Lily Schuld (formerly Stearns) on a question relating to Schuld’s mortgage.

Lily B. Stearns Homestead Application, Records of the General Land Office, Serial Patent Files, 1908–1951, Homestead Entry #018907 (Accession # 595690), Lily B. Stearns, RG 49, National Archives and Records Administration, Washington, DC.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

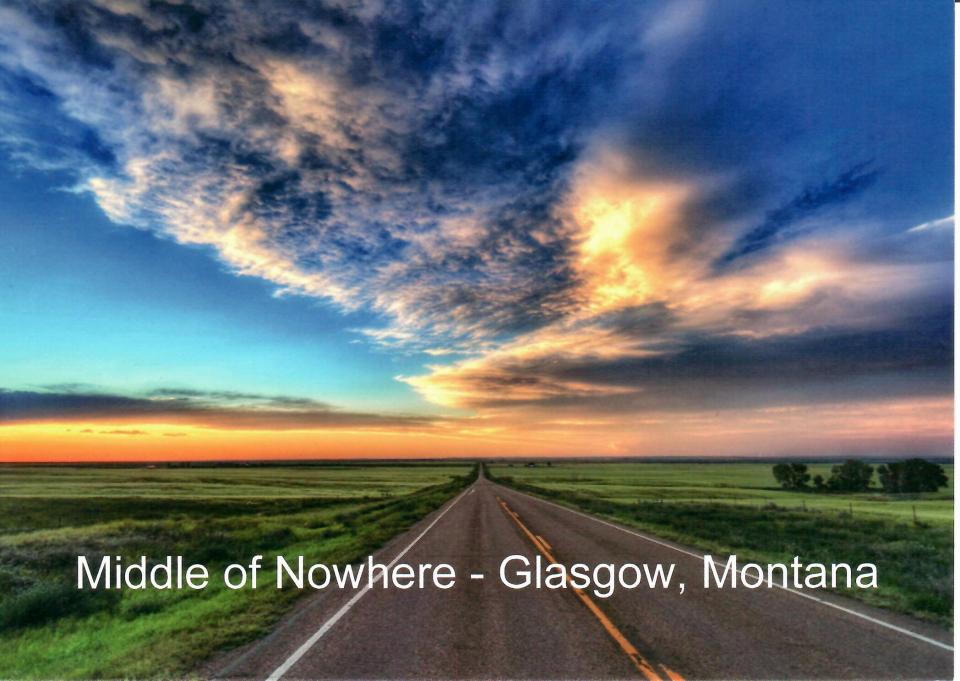

Ultimately, unpredictable weather and grain surpluses overwhelmed the inducements of free land and wartime prices, and the homestead boom in Montana dried up below the clear skies of the episodic El Niño-Southern Oscillation. The dry climate and abundant space conserve the traces of the land rush that remain visible in sprawling ranches and clusters of rusty machinery, but the mirage of free land and endless opportunity has long since faded from the ledgers of local businesses.

2018 postcard by Sean R. Heavey. “Glasgow, Montana, More of What Matters, In the ‘Middle of Nowhere’ you will find your sense of peace, place and pride.”

2018 postcard by Sean R. Heavey. “Glasgow, Montana, More of What Matters, In the ‘Middle of Nowhere’ you will find your sense of peace, place and pride.”

© 2018 Sean R. Heavey

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This part of northeastern Montana garnered newfound notoriety in 2018, as reporters for the Washington Post adapted geospatial datasets to determine that Glasgow was the “The Middle of Nowhere,” a designation used to locate the US city of more than 1,000 residents located farthest from a major urban center. Glasgow embraced the title with enthusiasm, and Valley County’s glorious landscape once again features prominently in local advertising. Local photographer Sean R. Heavey’s postcard, “Middle of Nowhere — Glasgow, Montana,” widely available around town, features an open road overshadowed by towering cloud formations that allude to the impetuous weather that continues to shape the livelihoods of those whose lives unfold within these wide-open spaces. Today, Valley County houses an average of 1.5 people per square mile, just over half the density of 1910 (2.8 people per square mile), and their fortunes remain tied to the grazing districts, farms, and small businesses that support Glasgow and the surrounding communities.

What remains: an abandoned car and farm equipment on the Stensland homestead adjoining Stearns’s land. Photograph by Sara Gregg, 2019.

What remains: an abandoned car and farm equipment on the Stensland homestead adjoining Stearns’s land. Photograph by Sara Gregg, 2019.

2019 Sara Gregg

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stearns’s story should be read within a broader interpretation of US history: the perpetuation of American myths of opportunity has demanded that in privileging individualism and self-determination we ignore the perennial constraints imposed by community, markets, and weather. Lily Stearns’s Montana years illustrate how her lifelong quest for security was shaped by the social networks, weather, and crop prices necessary for securing success on the Great Plains of North America. The rich experiences of the homesteaders who sought to cobble together a livelihood on their farms have shaped the demographics, culture, and politics of the US West, and the personal and environmental dramas embedded in their stories have contributed in material ways to shaping the understanding of American history on a global stage.