The Belly of the City

What lies hidden deep within Munich?

Although in many other cities the central slaughterhouses have long since been shut down, animals are still butchered in the middle of Munich even today.

“Butcher Shop,” Lovis Corinth, 1893.

“Butcher Shop,” Lovis Corinth, 1893.

Painting by Lovis Corinth, 1893. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

There are two slaughtering businesses on the grounds of the Munich slaughterhouse: one is for pigs and one for cattle, there are twelve meat wholesaler and two businesses, which sell on the meat.

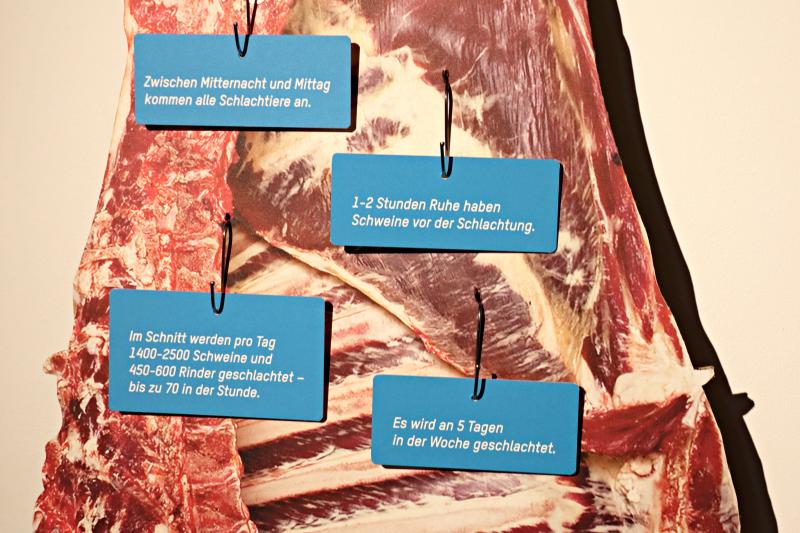

Facts about the Munich slaughterhouse:

* The pigs come from within a radius of 200 kilometers around Munich; the cattle come from as far away as Franconia. The transport to the Munich slaughterhouse takes up to three hours.

* All animals that are to be slaughtered arrive between midnight and noon.

* The pigs have a resting time of one to two hours before their slaughter.

* On average, 1400–2500 pigs and 450–600 cattle are being slaughtered—up to 70 per hour. The Munich slaughterhouse operates five days per week.

There are two slaughtering businesses on the grounds of the Munich slaughterhouse: one is for pigs and one for cattle, there are twelve meat wholesaler and two businesses, which sell on the meat.

Facts about the Munich slaughterhouse:

* The pigs come from within a radius of 200 kilometers around Munich; the cattle come from as far away as Franconia. The transport to the Munich slaughterhouse takes up to three hours.

* All animals that are to be slaughtered arrive between midnight and noon.

* The pigs have a resting time of one to two hours before their slaughter.

* On average, 1400–2500 pigs and 450–600 cattle are being slaughtered—up to 70 per hour. The Munich slaughterhouse operates five days per week.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

Graphic design by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng.

Used with permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Apart from the odor of blood and excrement, the living and dying taking place behind the slaughterhouse walls is invisible to most residents of Munich.

What traces does the abattoir leave in the everyday life of the city? The cow Bavaria—legendarily—escaped from it into the streets of the Bavarian capital. Is Weißwurst, the butcher shop bestseller, really a “typical Munich” delicacy? Where do the pigs and cattle come from? And what role did cholera play in the establishment of the facility?

Usually the animals in the slaughterhouse are invisible to Munich’s residents and visitors.

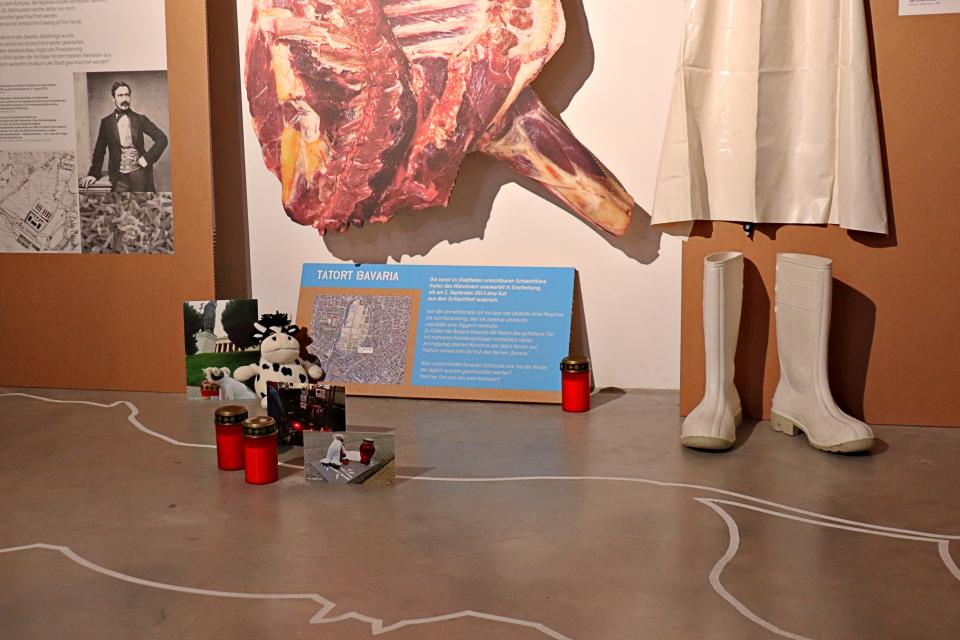

On 2 September 2014, a cow escaped the slaughterhouse. It ran from the slaughterhouse on Zenettistraße across the grounds of a mosque, all the way to the Theresienwiese. In the second half of September, this is where the famous Oktoberfest takes place. The cow circled the Theresienwiese twice, where it injured a runner. Near the statue of the Bavaria, the police shot the cow several times, killing the animal. On the next day, Munich residents came to the crime scene and lit candles. The cow was posthumously named “Bavaria.”

What makes the fate of “Bavaria” different from that of unnamed cows destined for slaughter? Whose death is being mourned and by whom?

Usually the animals in the slaughterhouse are invisible to Munich’s residents and visitors.

On 2 September 2014, a cow escaped the slaughterhouse. It ran from the slaughterhouse on Zenettistraße across the grounds of a mosque, all the way to the Theresienwiese. In the second half of September, this is where the famous Oktoberfest takes place. The cow circled the Theresienwiese twice, where it injured a runner. Near the statue of the Bavaria, the police shot the cow several times, killing the animal. On the next day, Munich residents came to the crime scene and lit candles. The cow was posthumously named “Bavaria.”

What makes the fate of “Bavaria” different from that of unnamed cows destined for slaughter? Whose death is being mourned and by whom?

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The approximate route the cow Bavaria took from the slaughterhouse on Zenettistraße around the Theresienwiese to the statue of the Bavaria, where the police caught up with it.

External link to a Google Map showcasing the approximate route the cow Bavaria took from the slaughterhouse on Zenettistraße around the Theresienwiese to the statue of the Bavaria, where the police caught up with it.

If you want to try a Bavarian Weißwurst, you can answer this checklist (in German). During the physical Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition, visitors were able to sample vegan Weißwurst.

Münchner Weißwurst, a Bavarian sausage.

Münchner Weißwurst, a Bavarian sausage.

Photograph by Rainer Z. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

At the exhibition, a selection of vegan and vegetarian Weißwurst was served. Visitors were able to sample the sausages and fill out a short questionnaire.

At the exhibition, a selection of vegan and vegetarian Weißwurst was served. Visitors were able to sample the sausages and fill out a short questionnaire.

Photograph by Laura Kuen.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Slaughterhouse tales: Grumbling in Munich’s belly

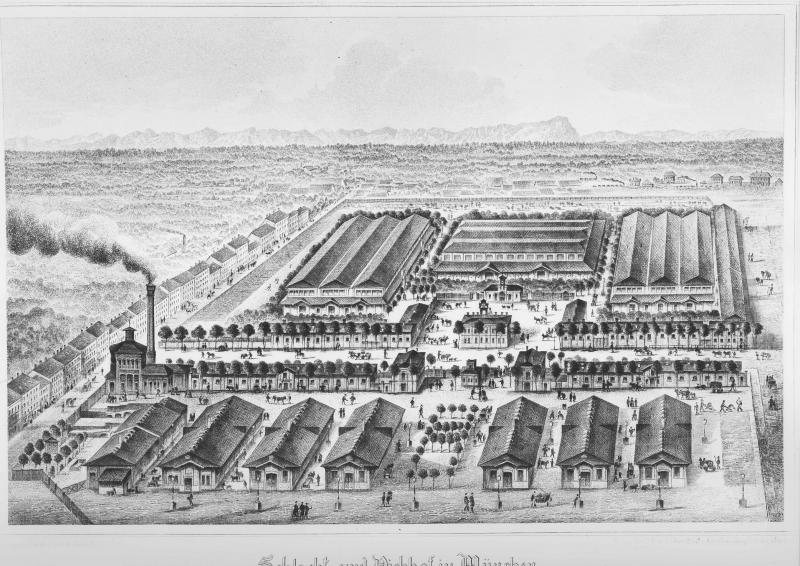

The Munich slaughterhouse was built between 1876 and 1878.

The Munich slaughterhouse was built between 1876 and 1878.

This drawing was created by an unknown artist. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

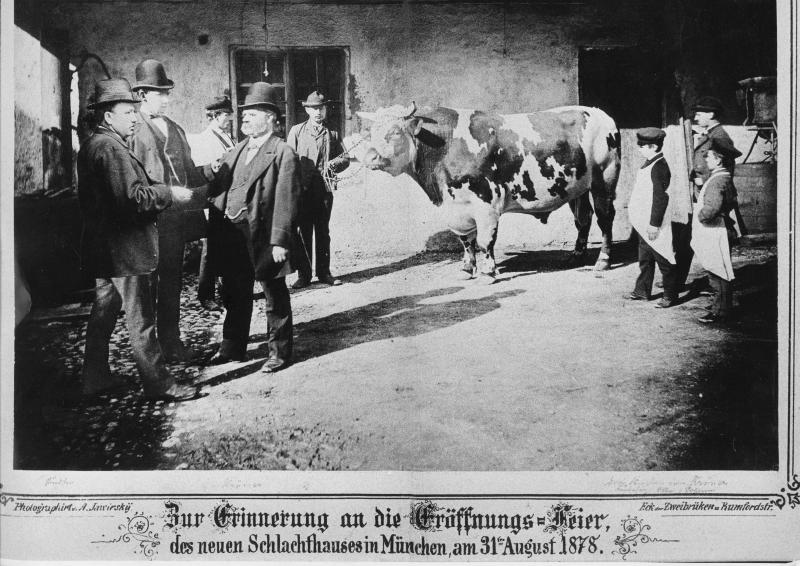

The opening of the Munich slaughterhouse in 1878. The architect, Arnold Zenetti, is the bearded person, fourth from the left.

The opening of the Munich slaughterhouse in 1878. The architect, Arnold Zenetti, is the bearded person, fourth from the left.

Photograph by A. Jawirsky. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Munich slaughterhouse is still located in the same place as when it was created in 1878, once at the edge of the city, now in its center. The architect Arnold von Zenetti built it following the model of the Paris market halls, famed as the “Belly of Paris.” Thus was born the “Belly of Munich.”

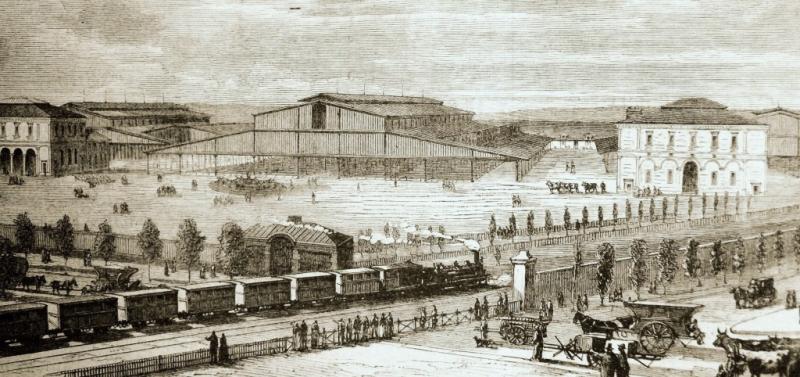

The architecture of the Paris market halls (1852-1870), which had been built during the reign of Napoleon III, served as a role model for Arnold von Zenetti.

The architecture of the Paris market halls (1852-1870), which had been built during the reign of Napoleon III, served as a role model for Arnold von Zenetti.

This painting was created by Felix Benoist, ca. 1870. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Paris slaughterhouse. In 1810, Napoleon Bonaparte banned the butchering within the city and relocated the slaughterhouses to the city’s outskirts. In 1867, the city’s slaughterhouse opened in La Villette and served as a European role model.

The Paris slaughterhouse. In 1810, Napoleon Bonaparte banned the butchering within the city and relocated the slaughterhouses to the city’s outskirts. In 1867, the city’s slaughterhouse opened in La Villette and served as a European role model.

Engraving by an unknown artist. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Prior to the construction of the central slaughterhouse, butchering took place in countless courtyards across the city. The chemist Max von Pettenkofer studied the connection between slaughterhouse waste, water supply, the sewer system, and cholera. He concluded that hygiene and sanitation needed to be improved. Starting in the nineteenth century, therefore, butchering was only permitted in slaughterhouses. This rule is still in effect today.

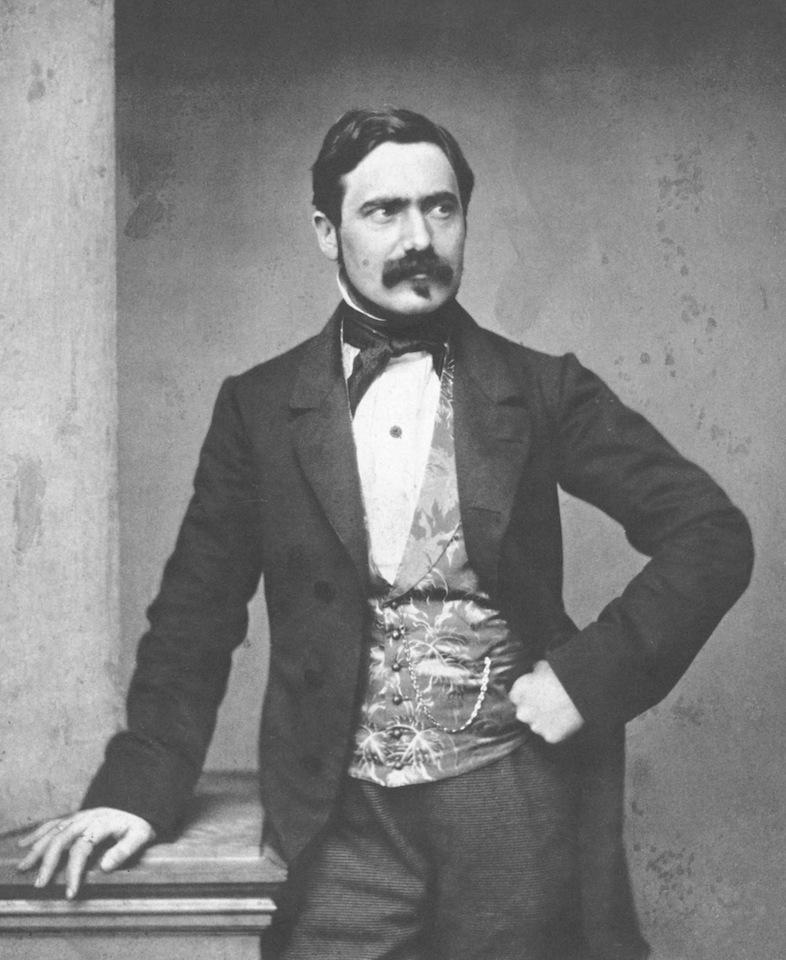

Max von Pettenkofer was the first hygienist in Germany who also engaged politically to improve hygiene and sanitation. These efforts included the supply of drinking water and the centralization of butchering, which were only allowed to take place in slaughterhouses.

Max von Pettenkofer was the first hygienist in Germany who also engaged politically to improve hygiene and sanitation. These efforts included the supply of drinking water and the centralization of butchering, which were only allowed to take place in slaughterhouses.

Photograph by Franz Seraph Hanfstaengl, ca. 1860. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

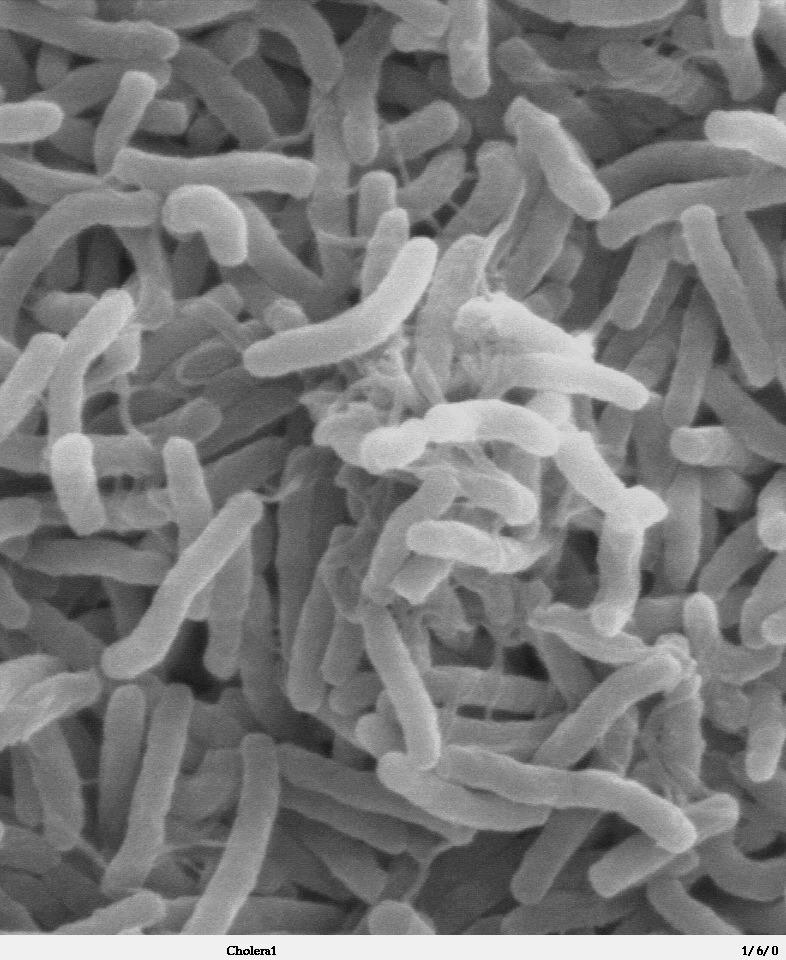

Munich was affected by cholera several times. 1854, the city hired Max Pettenkofer to analyze the spread of the disease. The cause was a lack of hygiene. The cholera bacteria was discovered only in 1883 by Robert Koch. Here you can see vibrio cholerae, the cholera bacteria through an electron microscope.

Munich was affected by cholera several times. 1854, the city hired Max Pettenkofer to analyze the spread of the disease. The cause was a lack of hygiene. The cholera bacteria was discovered only in 1883 by Robert Koch. Here you can see vibrio cholerae, the cholera bacteria through an electron microscope.

Photograph by T. J. Kirn, M. J. Lafferty, C. M. P Sandoe, and R. K. Taylor, 2000. It can be found here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

During the Second World War, in spite of heavy damages, the slaughterhouse continued to be used. After reconstruction, it was privatized. In 2040 the leases with most of the businesses that use it will expire. After that date, will slaughter still continue to take place in the belly of the city?

About the curators

Marc J. Bubeck

Marc J. Bubeck studied sociology and veterinary medicine at LMU Munich. In his final project for the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society’s Environmental Studies Certificate Program, he is following the topic of the slaughterhouse. Now, he works on his PhD thesis, which focuses on killing in veterinary medicine.

I had learnt about the Munich slaughterhouse during my studies; in fact, I examined the meat hygiene there. By preparing this exhibition, I have gained a new perspective on the slaughterhouse: not only about the foodstuff production but also about trade, subculture, and animals.

—Marc Bubeck

Alisa Udodik

In August 2019, Alisa Udodik has finished her master’s degree in cultural and cognitive linguistics. She is also part of the RCC’s Environmental Studies Certificate Program. She is interested in the relations between the environment and humans. Through the Ecopolis München 2019 exhibition, she has learnt much about new ways of science communication.

Today the topic of butchering is one of controversy, which is exactly why it was very interesting to engage with the topic further. To us, it was particularly important to illuminate the complex relations between evey day life and slaughtering.

—Alisa Udodik

How to cite: Bubeck, Marc J., and Alisa Udodik. “The Belly of the City.” In “Ecopolis München 2019,” edited by Katrin Kleemann. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2020, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/9022.