Stone-Rich

Where is Munich’s Gravel Hiding?

Munich: An Alpine City

What is Gravel In?

A Naked Visionary in Gravel

Who Can Live on Gravel?

Munich is situated on the largest gravel plain north of the Alps. Although rather unassuming, gravel is a versatile raw material that is present in our everyday lives and characterizes Munich’s cityscape. It is scattered across the grounds of popular beer gardens and is a basic component of our streets and houses. Gravel is used in the production of everyday objects, from toothpaste and glass to coffee cups. Through the products they use, every Munich resident goes through about seven tonnes of sand and gravel from the city’s gravel plain per year.

Gravel also influences soil formation and vegetation. In the flat countryside surrounding Munich, rivers and streams cut into the rocky subsoil and thereby form the city’s only natural slopes. Gravel provides a habitat for endangered animals and plant species. More than 130 years ago, a gravel pit became a refuge for humans. In gravel, an eccentric artist and visionary found a place for his creative work. Inoperative and renaturalized gravel pits in Munich’s countryside are now open as recreational areas to inhabitants, as well as to endangered species.

What makes gravel a typical Munich rock? And how do we connect with it?

Schematic geological map of the Munich gravel plain and the Alps by Alicia Dorner

Schematic geological map of the Munich gravel plain and the Alps by Alicia Dorner

Alica Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

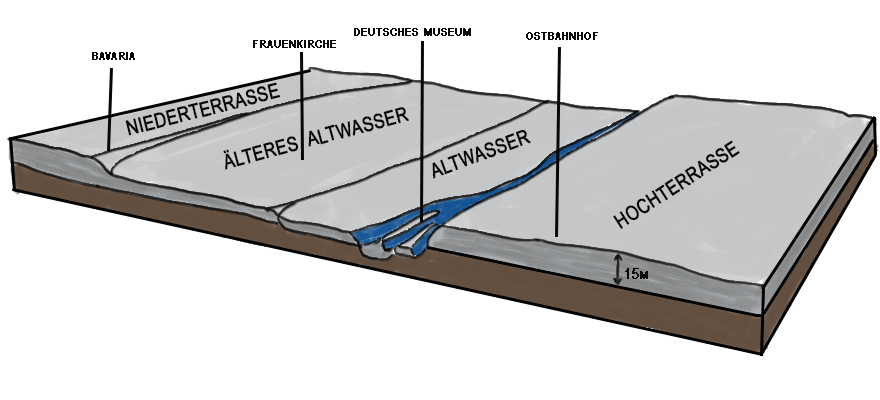

Schematic drawing of the Isar terraces in the Munich area by Stefan Bitsch

Schematic drawing of the Isar terraces in the Munich area by Stefan Bitsch

Stefan Bitsch (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Munich: An Alpine City

Over two million years ago, enormous ice sheets covered the Alps and formed glaciers that stretched all the way to Munich. Some of our recreational areas, like Lakes Ammer and Starnberg, are the remnants of advancing glacier tongues. The ice carried away vast amounts of rock mass from the Alpine peaks, and glacial rivers like the Isar transported boulders further north towards the Danube. Thus a typically flat and barren gravel plain developed, in the middle of which Munich was later built.

Munich grew on the slopes of the Isar terraces. Low-lying places, like Sendling, flooded often and so were reserved for the poorer inhabitants, whereas the higher-situated city center of the old town protected the elite. Munich residents faced the floods with customized architecture made of nagelfluh.

The word nagelfluh is German in origin. It refers to a chalky rock that consists of gravel, which was removed on a large scale from the slopes of the Isar. A highly porous and stable building material, it is ideally suited to the base of large buildings. After a flood, water is able to drain quickly, without compromising the rock’s strength.

Layers of clay lie beneath the nagelfluh in the stratigraphy; bricks were formed from this clay and used for the upper stories of buildings. One example is Munich’s municipal district Berg am Laim. Historic buildings still contain this classical construction.

What is Gravel In?

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of gravel and clay in historic buildings of Munich. View the images on the following pages.

Where is gravel hiding?

Alicia Dorner explores Munich with the intention of showing the many buildings that gravel has helped to build. Here she is next to a nagelfluh column at Marienplatz.

All photos are by Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Munich’s Städtisches Hochhaus is the city’s oldest high-rise building and has a typical composition of a nagelfluh base and clay construction.

A Naked Visionary in Gravel

Karl Wilhelm Diefenbach was a nineteenth-century artist whose opinions caused a stir throughout Munich. He appeared nearly every Sunday and openly flaunted and “preached” naturalness, freedom, and vegetarianism. Furthermore, he questioned strict monogamy.

Many of his contemporaries in heavily Catholic Munich considered his ideas to be strange at best, and scandalous at worst. They ridiculed him and his “disciples” as “kohlrabi apostles.” Because of his naked proclamations at Marienplatz, he was exiled from the city in 1885. From that point on, he lived at a nagelfluh quarry south of Munich for several years, in the small town of Höllriegelskreuth. Diefenbach became an icon for the nudist movement in Germany and set a new standard in terms of modern aesthetics—an early contribution to changed body awareness.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images of the Höllriegelskreuth Quarry. View the images on the following pages.

Inspired by Diefenbach’s style of dress, Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner dress up and pose in the remains of the Höllriegelskreuth Quarry.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Alicia Dorner in the remains of the Höllriegelskreuth Quarry, giving a sense of the scale of Diefenbach’s former living quarters. Image by Stefan Bitsch

Stefan Bitsch (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stefan Bitsch in the remains of the Höllriegelskreuth Quarry, giving a sense of the scale of Diefenbach’s former living quarters. Image by Alicia Dorner

Alicia Dorner

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner in the remains of the Höllriegelskreuth Quarry give a sense of the scale of Diefenbach’s former living quarters. Photos by Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Who Can Live on Gravel?

Gravel forms low-nutrient ground in which it is difficult for most plant life to thrive. However, gravel offers ideal conditions for undemanding heathers and heath plants like chamomile, daisy, and birch. The gravel pits are an ecological niche for displaced animal species and several specially adapted species find refuge here. The little ringed plover shies away from the hustle and bustle along the banks of the Isar and instead escapes to the gravel pits around Munich. What characterizes these special landscapes?

Vegetation Project

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images of the vegetation project by Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner. View the images on the following pages.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner collect rocks from the banks of the Isar in downtown Munich.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Washing the rocks that were collected

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

How much gravel is too much gravel? This case contains an example of the surface of a heath with typical grasses and flowering plants, filled with about 60% gravel and 40% nutrient-poor soil.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Installation view of the vegetation projects in the exhibition

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Documentation of the growth of the plants over a period of several months. Photos by Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The large case contains an example of the surface of a heath with typical grasses and flowering plants, filled with about 60% gravel and 40% nutrient-poor soil.

But how much gravel is too much gravel? The small case is filled with about 75% gravel and 25% nutrient-poor soil and seeds for wild flowers and grasses.

Examples of different types of rocks typically found in Munich

Examples of different types of rocks typically found in Munich

Image by Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Profiles of Rocks

What kind of rocks are common in Munich? And where do they come from? These are examples of rocks typically found in Munich that were washed from different locations in the Alps (clockwise from bottom left).

Sandstone: Compacted sand grains and rock fragments, which are calcareous, its origin is the “Flysch zone” (for example, Benediktbeuern).

Limestone: Known colloquially as Meeresfriedhof (sea graveyard) in German, it originates from dead sea creatures with calcareous shells, often single-cell organisms that sink into the seabed after death. Its origin is the Northern Limestone Alps.

Slate: With its distinctive glittering, plate-like mica minerals, slate has a preferred arrangement of minerals because of the pressure at which they are formed. Its origin is the Central Alps.

Granite/Granodiorite: Rocks created at depth by high pressure and temperature conditions during the formation of the Alps, granite’s origin is the Central Alps geological boundary (for example, the Engadin window).

Eclogite: Ironman der Gesteine (ironman of the rocks) is created by high pressure and temperature conditions at a depth of around 30 kilometers. Its origin is the Central Alps (for example, Ötztal Crystalline). Eclogite also marks, among other things, the contact seam between the Apulian (Italian) plate and the European plate and the geographical border with Africa at the meridian of Ruhpolding.

Shell Limestone: Fossilienkalk (fossil lime) is stained limestone with shell fragments. The red coloration is due to the accumulation of iron, and its origin is the Northern Limestone Alps.

Curators: Stefan Bitsch and Alicia Dorner

How to Cite: Bitsch, Stefan, and Alicia Dorner. “Stone-Rich.” In “Ecopolis München,” edited by L. Sasha Gora. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2017, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/7964.