Thinking Waste

Waste is a question of perspective. As anthropologist Mary Douglas put it, dirt is “matter out of place.” Within social systems, waste represents the inappropriate, the rejected, and the excluded. Waste is what we want to discard. Differences exist in terms of what items a society or individuals deem inappropriate, and when. Second-hand stores, for instance, live off the idea that what one person no longer wants, another may desire. Starting in the 1970s, various countries around the world established industrial waste exchange programs. Their idea is also based on the mutability of waste objects—what one company may look at as waste, another might still find useful for its production. For instance, a chemical company’s castoff fluoride compounds may come in handy for another company’s production of toothpaste. Waste owns a culturally, socially, and also technologically determined mutability.

A singular waste object at an abandoned waste dump in Brandenburg. Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2018.

A singular waste object at an abandoned waste dump in Brandenburg. Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2018.

Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

At the same time, waste is contentious beyond its cultural denaturalization, social rituals, symbolic meanings, and technological appropriateness. Waste objects marry cultural conceptions with economic realities and with biological and chemical processes of permeability, alternation, and vulnerability. It is easier to be wasteful when you have the economic means to live a luxurious lifestyle. So far, nobody has found a legal platform for the reuse of nuclear waste. Similarly, outdated pesticides in corrosive containers present a health and environmental hazard no matter how you look at it.

Waste used in a normative sense entails a category of moral judgment. We should not waste—not our time, our money or our lives. Waste is at the heart of so many moral economies that it is difficult to find any sense in which it is not bad, argues Gay Hawkins. At the same time, in modern commodity cultures wasting also entails a sense of material abundance and of freedom—the freedom to waste, to discard objects that are still perfectly useful. Advertising often plays on this very notion of freedom—the liberty to consume at will—wherever and, now with online shopping, also whenever. Click through the gallery below to learn more about how we “think” waste.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of book and film profiles and articles showcased on the Environment & Society Portal. View the individual gallery items online or in the appendix of this PDF.

The idea of purity is a central question for every society. Mary Douglas explains its relevance and its wide-ranging impact on our attitudes, values, cosmology, and knowledge. The book has been hugely influential in many areas of debate—from religion to social theory. But perhaps its most important role is to offer each reader a new explanation of why people behave in the way they do. (Adapted from Routledge, Taylor & Francis)

Learn more

Gay Hawkins explores the ethical significance of waste in everyday life—from the broadest conceptions of waste to how the environmental movement has affected the ways we think about garbage, the ways we deal with it, and the ways in which we view others’ reactions to waste. He seeks ways to change ecologically destructive practices without recourse to guilt, moralism, or despair. (Adapted from Rowman & Littlefield)

Learn more

Rubbish is something we ignore. We discard it, from our lives and minds, and it remains outside the concerns of conventional economics. However, rubbish can re-enter circulation as a prized commodity, far exceeding its original value. This edition includes a new afterword revealing how the consequences of our compulsion to discard are far from inevitable, and how we can transform our wastes into valuable resources. (Adapted from Pluto Press)

Disposal causes not only mountains of rubbish that occasionally threatens to overwhelm us; it also creates other “garbage,” particularly the dead ends of useless knowledge and the often abject reality of our disposable lives. Garbage is not only material waste, but also “broken” knowledge, remainders of systems of intellectual and cultural thought. It turns out that we have become the garbage of our times. (Adapted from Reaktion Books)

Learn more

One of the most difficult challenges of our society is hazardous waste and its risks posed to human health and the environment. Numerous case studies illustrate how hazardous waste mismanagement has led to disastrous consequences and highlights the deficiencies in science and regulation that have allowed the public to be subjected to myriad potentially hazardous agents. (Adapted from Elsevier)

Waste objects can also form entire landscapes. They can be wastelands as well as wasted lands. Think of the island of floating plastic in the middle of the Pacific or underground atomic waste storage sites, the wastewater pools of mines or those waste conglomerates collected in landfills.

The original virtual exhibition includes the vimeo short film “Ilha das Flores (Island of Flowers)” by Filipe Bessa. A short film directed by Jorge Furtado (1989). The ironic, heartbreaking and acid “saga” of a spoiled tomato. 12:33 min.

Waste can take many forms, from your broken computer, the empty milk container or your torn T-shirt, to a container of outdated chemicals, a pond of oil sludge or an outdated ocean carrier ready for scraping. Director Rahmin Bahramin revisits the life of a particular waste object from an environmental perspective: the life of a plastic bag. Similarly, the short film Ilha das Flores centers its narrative on a spoiled tomato as it moves through the Brazilian food chain.

“Waste Dump.” Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2018.

“Waste Dump.” Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2018.

Photograph by Jonas Stuck, 2018.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 3.0 Unported License.

These waste(d) lands are never still. They change surely—albeit slowly—over time. When we waste, we are never just wasting on our own resources, but those of future generations as well.

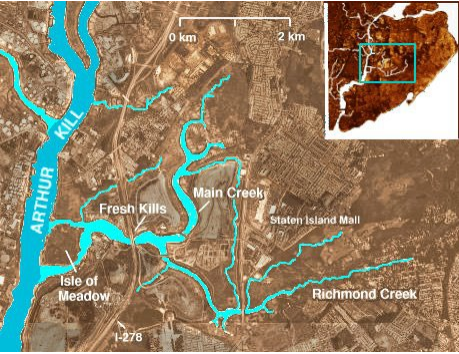

An impressive example of a transient waste space is Fresh Kills landfill in New York, as Martin Melosi explores in his article, “ Fresh Kills: The Making and Unmaking of a Wastescape”. The former salt marsh is today the largest human-engineered formation in the world. Over its long history, it has changed from landfill to cemetery to park. Fresh Kills opened its doors to New York City’s garbage in 1948. By the mid-1980s, it was New York’s only landfill. In March 2001, city officials gave in to local protests and closed down the landfill with great fanfare—only to reopen it some months later after the Al-Qaida attacks in 2001, to receive human remains and debris from the Twin Towers. After 9/11, as well as being a landfill, Fresh Kills equally became a burial place and guardian of many a human story that will likely never be forgotten.

“Fresh Kills Landfill is on the western edge of Staten Island.” Photograph by Matthew Trump. Figure 1 in Martin V. Melosi’s article, “Fresh Kills: The Making and Unmaking of a Wastescape.”

“Fresh Kills Landfill is on the western edge of Staten Island.” Photograph by Matthew Trump. Figure 1 in Martin V. Melosi’s article, “Fresh Kills: The Making and Unmaking of a Wastescape.”

Photograph by Mathew Trump, via Wikimedia Commons.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.