Travel and reception of Leichhardt’s letters to his family

1866—The letters’ appearance in the Australian press

1881—Publication of Leichhardt’s Briefe an seine Angehörigen

1888—Mann tries to settle accounts: Eight Months with Dr. Leichhardt

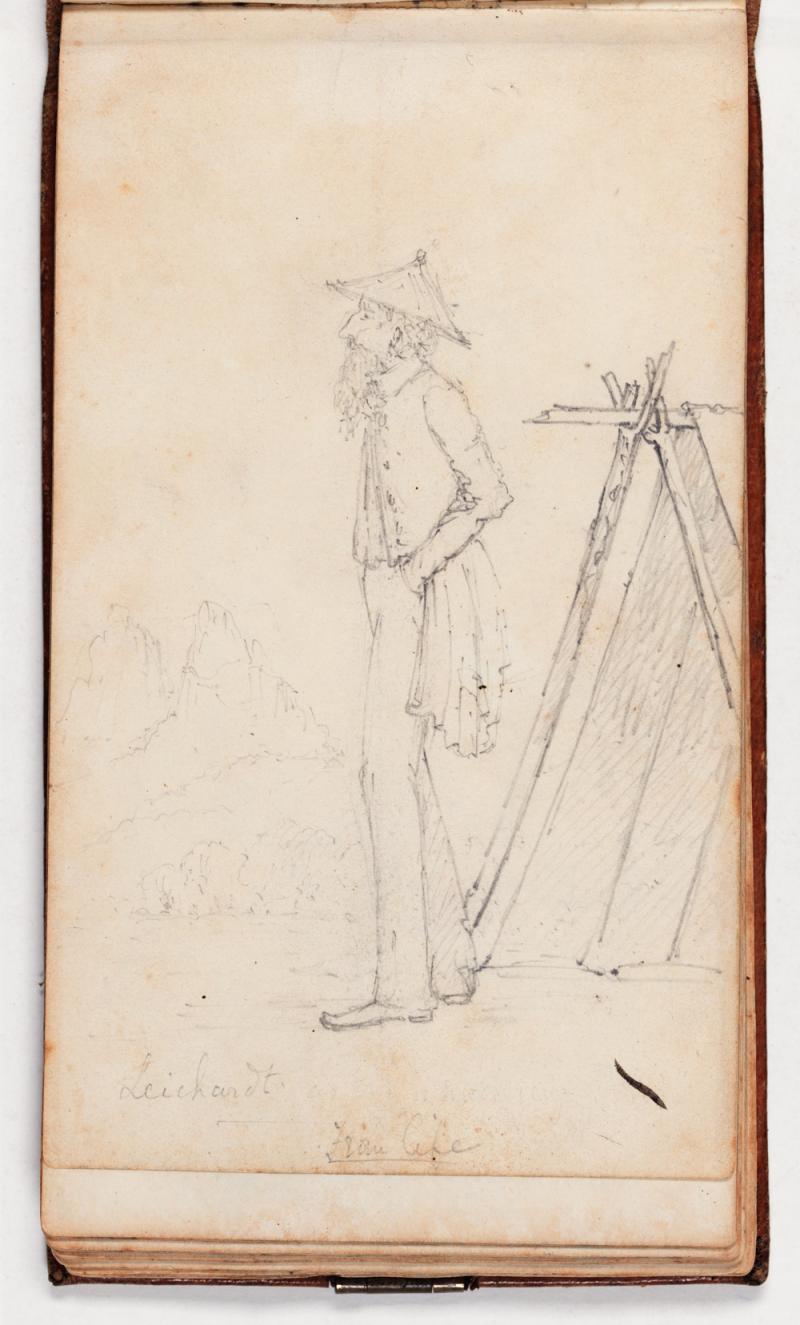

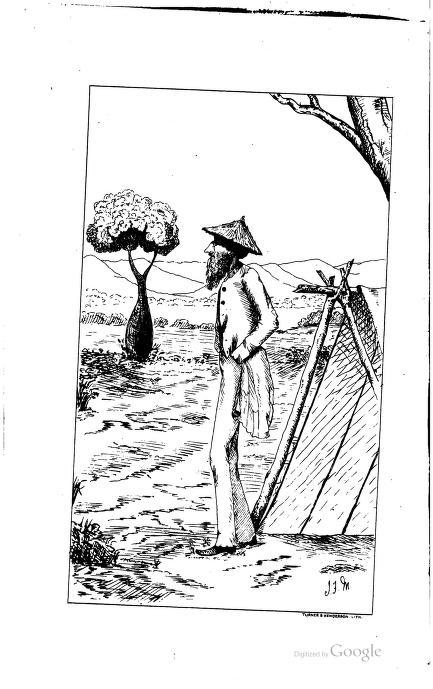

Drawing of Ludwig Leichhardt by expedition member John F. Mann

Drawing of Ludwig Leichhardt by expedition member John F. Mann

Created by John F. Mann, 1846/47.

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Ludwig Leichhardt’s letters reached a wide public before finally ending up in the archive of the Deutsches Museum; they have contributed substantially to the contradictory portrait of this “Prince of Explorers.” Without them, one of the most important portraits of Leichhardt would probably never have been circulated, and the life of its artist, John F. Mann, might have been a quieter one.

Originally Leichhardt hoped that his correspondence with his family might be connected with a publication—in the best case, a profitable one. Half a year after his arrival in Australia, he proposed that his relatives should see if a publisher were interested in “a publication in the form of letters” so that he could “be of use to you by ceding you the honorarium” (letter to his mother, 6 September 1842). His most frequent correspondent was his brother-in-law, Friedrich August Schmalfuß, a music and drawing teacher in Cottbus. Schmalfuß spoke with scientists and publishers regarding the publication of the letters. But Leichhardt advised him to be cautious: “I am of course pleased that educated men, not just the consideration and greater interest of a friend, deem them worthy of publication. Yet there are things I write which I would not wish to see appear in print” (letter to F. A. Schmalfuß, 21 October 1847). A few weeks later, Leichhardt departed on his last expedition, from which he never returned.

Leichhardt’s unknown fate has made him an object of fascination. In the years and decades after his disappearance, new rumors and theories spread regarding his choice of route and how the expedition met its end. Search missions—sent out from various places in the Australian colonies in hopes of finding survivors, graves, or material traces of the expedition—became matters of public interest; however, they all returned without concrete results. In Leichhardt’s homeland, Schmalfuß continued to try to publish his letters posthumously. In 1855 he asked Alexander von Humboldt to write a foreword and solicited support from the geographical society in Berlin—in vain, as he commented in the family chronicle. But the letters were in circulation, and along their meandering route they became important for Leichhardt’s historical reception. Their history also sheds light on the extensive scientific networks that arose in the mid-nineteenth century as a wave of German scientists emigrated to Australia. Thus, in 1907, it was a German returned from Australia, Georg von Neumayer, who gave the letters to the archive of the Deutsches Museum in Munich.

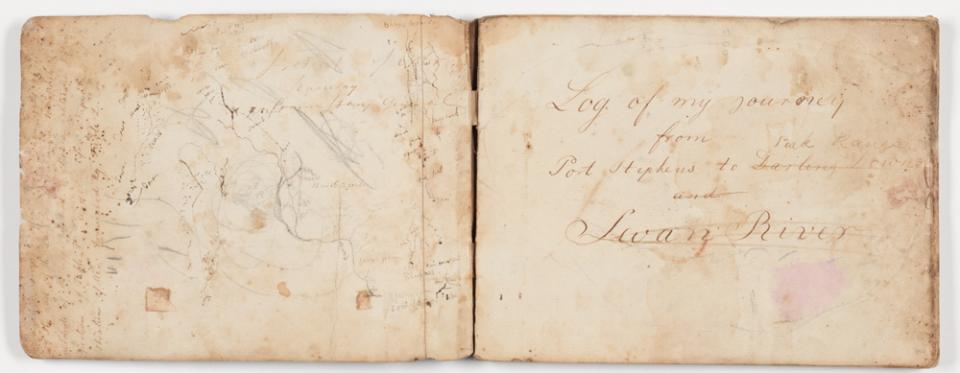

When Ludwig Leichhardt set out in 1846 to become the first European to cross the Australian continent from east to west, he confidently listed the starting point and destination: Port Stephens and Swan River (in the area of present-day Perth). But the expedition was forced to turn back at Peak Range.

When Ludwig Leichhardt set out in 1846 to become the first European to cross the Australian continent from east to west, he confidently listed the starting point and destination: Port Stephens and Swan River (in the area of present-day Perth). But the expedition was forced to turn back at Peak Range.

Log of My Journey from Port Stephens to Peak Range. Drawing by Ludwig Leichhardt,1 October 1846–3 November 1847.

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

1866—The letters’ appearance in the Australian press

The German geophysicist and astronomer Neumayer

The German geophysicist and astronomer Neumayer

During his stay in the colony of Victoria from 1857 to 1864, Georg von Neumayer established the Flagstaff Observatory.

Portrait based on a photograph by Frederick Frith, in Australian News for Home Readers, Melbourne: Ebenezer and David Syme, 25 July 1864.

Courtesy of the State Library of Victoria, Melbourne.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

When Leichhardt’s letters to his family reached the Australian press in 1866, they triggered the first public debate about his character and his capability as an expedition leader. Among Leichhardt’s most vocal critics were some of the men who had accompanied him. Leichhardt had recruited them himself on location while planning for the expedition, which was undertaken without government sponsorship or funding from Europe. On the other side were German scientists, who played a leading role in the exploration of the Australian continent starting in the mid-nineteenth century. They saw Leichhardt as an important point of reference and dedicated themselves to discovering his fate.

Among them were the brothers Richard Schomburgk, a botanist, and Otto Schomburgk, a publicist, who had emigrated to Australia during the Revolutions of 1848, the botanist Ferdinand von Mueller in Melbourne, the zoologist Gerard Krefft, and the geophysicist Georg von Neumayer.

The German-born botanist Ferdinand von Mueller

The German-born botanist Ferdinand von Mueller

Ferdinand von Mueller emigrated to Australia in 1847. In 1857 he became the director of the botanical garden in Melbourne, and he soon came to be considered one of the most influential scientists of the Australian colonial period.

Photograph by Johnstone, O’Shannessy & Company Limited, Melbourne, 1864.

Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

In early 1866 several of Leichhardt’s last letters to his family were published in the Sydney Morning Herald. They had already been published by the Schomburgk brothers in a German-language newspaper in Australia, and were now made available to a larger, English-speaking audience. At this time the search expedition organized by the Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Committee, initiated by Ferdinand von Mueller, was the focus of much public interest, and the German botanist was evidently also involved in the—in places misleading—translation of the letters. Of particular interest was a letter that Leichhardt wrote in 1847, in which he blamed his travel companions for the failure of the expedition to Swan River (letter to F. A. Schmalfuß, 20 October 1847).

John F. Mann, the second-in-command of the expedition, wrote a letter to the editor defending himself. He accused Leichhardt of poor leadership and bad decisions, adding that he was speaking out against “a tacit consent to that kind of hero-worship that can imagine no defect in its object, and that can even paint it in glowing colours without the faintest idea of a dark shade in the picture.” A few days later another member of the expedition, Hovenden Hely, spoke out in defense of Mann’s honor, publishing an additional letter of Leichhardt’s that portrayed his companions in a more positive light. The German zoologist Gerard Krefft, who was in charge of Leichhardt’s papers and collections in his capacity as curator at the Australian Museum in Sydney, used the opportunity to publish a biographical sketch of Leichhardt. In July the news arrived of the death of the leader of the Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Expedition. Again, Leichhardt had still not been found—but his image had become more contradictory.

The departure of the Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Expedition was a major occasion. The search expedition was expected to take two years. In addition to 40 horses, the members also took 14 camels with them.

The departure of the Ladies’ Leichhardt Search Expedition was a major occasion. The search expedition was expected to take two years. In addition to 40 horses, the members also took 14 camels with them.

Nicholas Chevalier (1828–1902), in: Australian News for Home Readers. Melbourne: Ebenezer and David Syme, 25.7.1865. Berlin, Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin—Preußischer Kulturbesitz, Slg. Darmstaedter, Forschungsreisen/Australien, Australien 1844: Leichhardt, Ludwig Bl. 32.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

1881—Publication of Leichhardt’s Briefe an seine Angehörigen

In Leichhardt’s homeland, his nephew, Otto Leichhardt, took over the task of publishing Leichhardt’s letters after Schmalfuß’s death in 1876. Later the influential geophysicist Georg von Neumayer joined as coeditor, and in 1881 the volume Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt’s Briefe an seine Angehörigen (“Ludwig Leichhardt’s Letters to His Relatives”) appeared under the auspices of the Geographical Society of Hamburg. Von Neumayer lived in Australia from 1857 to 1864; he established the observatory in Melbourne and undertook long geomagnetic field studies. After his return to Germany he became well respected as a polar explorer and head of the Deutsche Seewarte, the marine observatory of the imperial navy in Hamburg. His efforts to solve the mystery of Leichhardt’s disappearance were untiring. In 1868 he attempted to convince the British Royal Society to undertake a search expedition into the unexplored interior of the Australian continent, as well as seeking support from other sources, but he was unsuccessful.

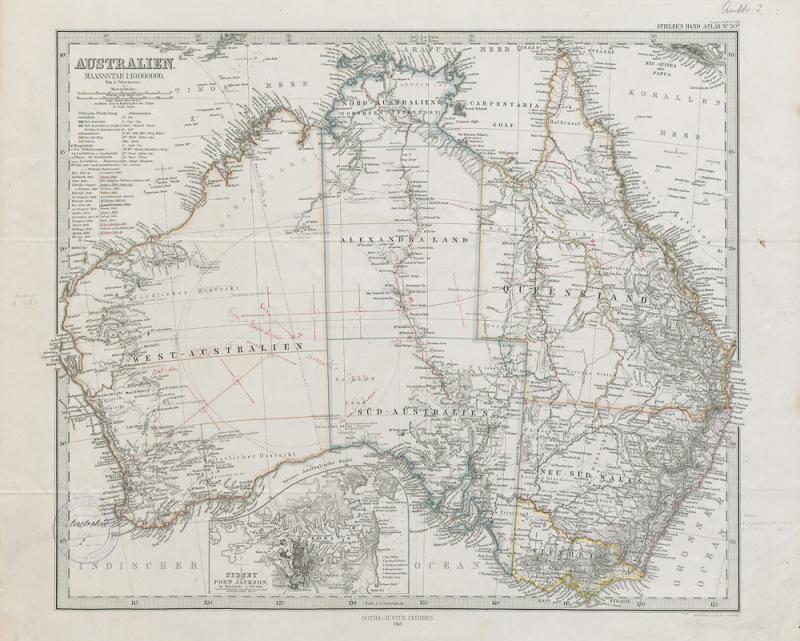

Neumayer tried to organize a search for Leichhardt in the western part of the Australian interior. The prestigious geographical journal Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen published his plans and created this preliminary map. Übersicht des Standpunktes der geographischen Kenntniss von Australien, 1868, & Dr. Neumayer’s Projekt zur wissenschaftlichen Erforschung Central-Australiens.

Neumayer tried to organize a search for Leichhardt in the western part of the Australian interior. The prestigious geographical journal Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen published his plans and created this preliminary map. Übersicht des Standpunktes der geographischen Kenntniss von Australien, 1868, & Dr. Neumayer’s Projekt zur wissenschaftlichen Erforschung Central-Australiens.

Gotha: Justus Perthes, 1868.

Courtesy of the Universitäts- und Forschungsbibliothek Erfurt/Gotha. Sammlung Perthes, Kartensammlung.

The volume with Leichhardt’s letters included his letters from Australia as well as earlier correspondence from his time as a student in Europe. In the foreword Neumayer explained that in his role as editor he had removed personal details from the letters, in accordance with the express wishes of the author. Included in the volume was also a map that showed the route of Leichhardt’s journeys and that of the search expeditions, as well as the location where von Neumayer believed that Leichhardt had met his end. In an appendix Neumayer included an essay “Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt als Naturforscher und Entdeckungsreisender” (“Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt as a Natural Scientist and Explorer”), in which he discussed the rumors and the search parties that have become as much a part of Leichhardt’s story as his disappearance. A portrait of Leichhardt as a young man was chosen as the frontispiece; it was created based on pictures in possession of family members.

Cover of Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt’s Briefe an seine Angehörigen (“Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt’s Letters to His Relatives”). Edited by Georg von Neumayer and Otto Leichhardt. Hamburg: L. Friederichsen, 1881.

This book is part of the collection held by the Bodleian Libraries and scanned by Google, Inc. for the Google Books Library Project. View source.

Courtesy of the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 UK: England & Wales License.

When the volume Dr. Ludwig Leichhardt’s Briefe an seine Angehörigen was published in 1881, new fire was given to the rumors in Australia about Leichhardt’s disappearance. A bushman claimed to have found a tree with the initial “L” engraved in it, as well as Leichhardt’s field notebook and other relics of the 1848 expedition. The German consulate in Sydney asked Georg von Neumayer to assess the plausibility of these claims; Neumayer was eager to believe them. In January 1882 the Sydney Morning Herald published a review, originally written for Atheneum, of the collection of letters. The review repeated Leichhardt’s criticism of the reliability of his traveling companions. Once again John F. Mann responded to the accusation in a letter to the editor and claimed to possess documents that would disprove Leichhardt’s statements.

1888—Mann tries to settle accounts: Eight Months with Dr. Leichhardt

Another eight years passed before John F. Mann published his version of the expedition in a book titled Eight Months with Dr. Leichhardt, in the Years 1846–47. Leichhardt himself had not published any official report of the unsuccessful expedition; the only account that had previously appeared was that of the British botanist and expedition member Daniel Bunce, printed in an Australian newspaper in 1805 and in German translation in 1857. When Mann’s book came out, four decades had passed since the completion of the expedition and the information about the regions they had traversed was obsolete—the land had since been settled. Instead, Mann focused on the portrayal of the social interaction during everyday life on the expedition. He spoke harshly of Leichhardt’s lack of “comradeship” and practical knowledge, stressing that he was only interested in making the truth known, and called upon the records of other expedition members for confirmation of what he described.

As second-in-command on the expedition, John F. Mann recorded the surrounding landscape and everyday life of the expedition through sketches, including this portrait of Leichhardt in profile.

Drawing by John F. Mann, Sketchbook, 1846–1847.

Courtesy of State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

One of Mann’s drawings shows Leichhardt privileging himself in the allotment of rations and parodies his German accent.

Drawing by John F. Mann, Sketchbook 1846–1847.

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Another drawing caricatures Leichhardt’s inability to handle the pack animals.

Drawing by John F. Mann, Sketchbook, 1846–1847.

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Frontispiece of Eight Months with Dr. Leichhardt

Frontispiece of Eight Months with Dr. Leichhardt

For the frontispiece of his travelogue Eight Months with Dr. Leichhardt, in the Years 1846–47 John F. Mann reworked a drawing he had made of Leichhardt during the trip, adding an Australian bottle tree.

John F. Mann, Sydney: Turner & Henderson, 1888.

This book has been digitized by Google from the library of the New York Public Library and uploaded to the Internet Archive by user tpb. View image source.

As for the reason for which he was not content to let the matter rest, Mann told the press that Neumayer’s edition of the letters—and thus the accusations made against his person—were to be found “upon the shelves of every kindred Society throughout the civilized world.” Mann’s book did not reach the same broad audience. But the surveyor was skilled at drawing, and during the expedition he had made a number of caricatures of Leichhardt in his sketchbook. He chose a drawing of Leichhardt standing before a tent as the frontispiece of his report.

This sketch portraying Leichhardt as a lanky eccentric who seems little at home in the Australian landscape made a lasting impression, and continues to be published widely today.

The travels of Leichhardt’s letters reveal the scientific networks between Germany and Australia in the second half of the nineteenth century, as well as offering an impression of the fascination surrounding Leichhardt’s disappearance and the prestige that finding him, or at least an explanation of his fate, would have offered. Their story also makes clear how certain voices won out over others in the struggle for recognition and remembrance. Travel reports solidified the authority of particular individual explorers, while their traveling companions and the collective trials and tribulations generally faded into obscurity.

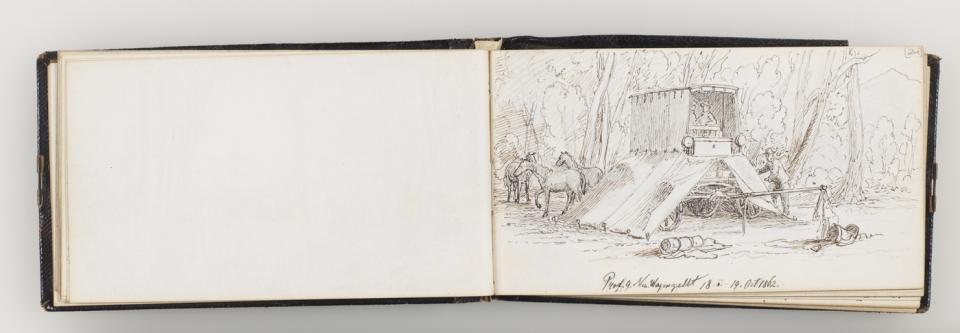

On his many scientific expeditions Georg von Neumayer took geomagnetic measurements. The renowned artist Eugène von Guérard accompanied him in 1862 to Mount Kosciuszko, where he sketched the wagon in which Neumayer transported his scientific instruments.

On his many scientific expeditions Georg von Neumayer took geomagnetic measurements. The renowned artist Eugène von Guérard accompanied him in 1862 to Mount Kosciuszko, where he sketched the wagon in which Neumayer transported his scientific instruments.

Drawing by Eugène von Guérard, in Sketchbook XXXIII, No. 15, Australian Colony Victoria, 18–19 October 1862.

Courtesy of The State Library of New South Wales, Sydney.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.