The Third Decade and Beyond: Radical Environmentalism in the Twenty-First Century

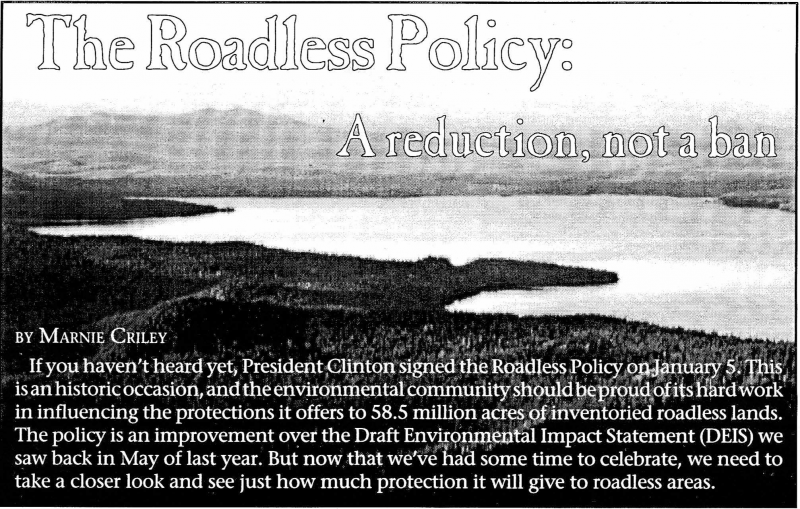

While these sorts of tactics have drawn the bulk of the media’s attention to these movements, significant environmental victories have been won, or contributed to, by radical environmentalists. In January 2001, for example, the United States Forest Service under President Bill Clinton issued the Roadless Area Conservation Rule, which protected over 25 million hectares (58 million acres) of federal forest lands. Although it took more than a decade of legal battles for opponents of this rule to exhaust their legal challenges to it, it eventually became the law of the land. It is inconceivable that the government would have issued this important rule in the absence of a decade of strong and disruptive resistance to the Forest Service’s timber program by radical environmentalists. Although the rule did not provide everything radical environmental activists sought, it was a significant advance for biodiversity conservation in North America. (It was more than ten years before lawsuits challenging the rule were finally exhausted. For the decisive 21 October 2011 ruling in Wyoming v. United States Department of Agriculture, see here. This decision was confirmed on 1 October 2012 when the Supreme Court of the United States declined Wyoming’s appeal; see “US Supreme Court Supports Clinton’s Roadless Rule.”)

Roadless Area Conservation Rule. See Earth First! Journal 21, no. 3.

Roadless Area Conservation Rule. See Earth First! Journal 21, no. 3.

© Earth First! Journal

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Within a year of this ruling, however, the 11 September 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center occurred, ushering in a very difficult period for the movement. While its campaigns continued, the federal government dramatically increased funding to apprehend activists involved in what it deemed “‘ecoterrorism’,” and it dramatically increased the prison terms for any acts so considered.

In December 2005, federal law enforcement officials then made the initial arrests of a half dozen Earth Liberation Front activists, and soon the number of convicted activists rose to nearly twenty, with several others becoming fugitives after, or in anticipation, of, being indicted. About two-thirds of the arrestees cooperated and named others whom they claimed were involved. Meanwhile, friends of the various activists debated, sometimes stridently, whether those who cooperated should be shunned or shown sympathy and supported. Much of the movement’s energy and focus turned to giving support to the non-cooperating defendants and prisoners.

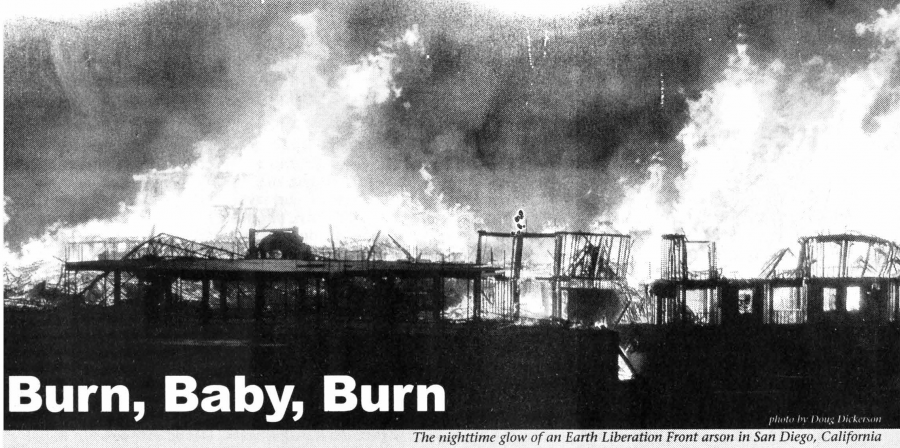

ELF accepted responsibility for one of the largest environmental sabotage in US history in San Diego, California. Activists started a fire that destroyed an unfinished five-story condominium complex on 1 August 2003. ELF credited themselves through a painted slogan on the building: “If you build it—we will burn it. E.L.F.” See Earth First! Journal 23, no. 6.

© Earth First! Journal

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

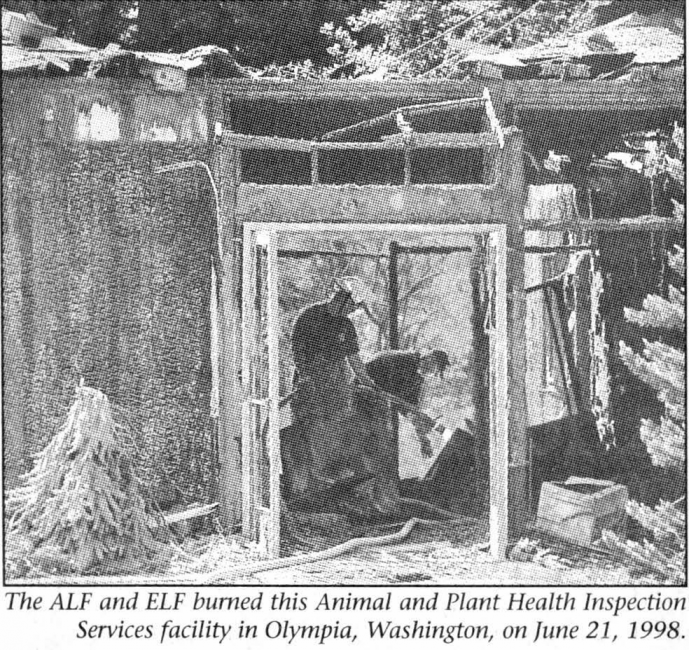

The Animal Liberation Front and Earth Liberation Front took joint responsibility for the burning of Animal and Plant Health Inspection Services buildings in Washington State. Damages were estimated to be almost $2 million. See Earth First! Journal 26, no. 2.

Photograph by Peter Haley.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

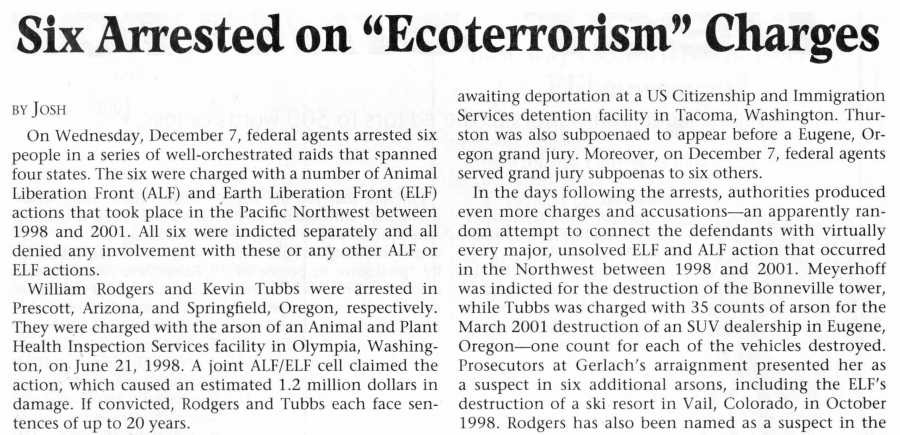

A 2006 article by “Josh” detailing the spate of federal arrests across four states for ALF and ELF actions between 1998 and 2001. See Earth First! Journal 26, no. 2

© Earth First! Journal

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

To view the caption and the source information, please click on the i in the upper left part of the image. Click on the images for a larger format.

While campaigns against deforestation continued, a great deal of discussion in the journal focused on how to build a non-hierarchal movement in which people with diverse identities— – ethnic, gender, and sexual— – could feel safe. Other movement activists felt that, although “Earth First!” remained the title of the journal, the moniker no longer defined the movement. The movement seemed to shrink further in the light of internal divisions and the state’s repressive power, and many of its activists considered it moribund.

During the same period, however, a new generation of activists assumed responsibility for the journal and some of them sought to rekindle the biocentric vision that originally animated the movement, fusing it to the by-then prevailing egalitarian, anti-capitalist, and anarchistic ideology. Tensions within the movement as well as efforts toward reconciliation and regrouping can be seen in the journal’s pages during the early twenty-first century and beyond, along with concurrent attention to and support for ecological resistance movements around the world.

The Deep Green Resistance radical environmental group, modeled after the book of the same name, sought to dismantle industrial civilization. Earth First! members had both positive and negative responses to Deep Green Resistance, which viewed most environmental activism as unproductive.

The Deep Green Resistance radical environmental group, modeled after the book of the same name, sought to dismantle industrial civilization. Earth First! members had both positive and negative responses to Deep Green Resistance, which viewed most environmental activism as unproductive.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

After the trials were over there also appeared to be signs of a rekindling of the most radical forms of militant environmental resistance. Just as a new moniker for a more radical form of resistance emerged in 1992 with the Earth Liberation Front, another new, radical environmental group took up the cause, labeling their movement Deep Green Resistance, using arguments that were not really new: that the only solution to ecological devastation and social inequality is to end industrial civilization and by whatever means necessary. Like the most militant environmental activists a decade earlier, the group, led foremost by writer and activist Derrick Jensen, contended that electoral politics and lobbying, as well as educational and other reformist conversion strategies that prioritize increasing awareness and changing consciousness, have been ineffective, in part, because agricultural civilizations are established and maintained by intimidation and violence, and are inherently destructive and unsustainable. The only viable solution therefore, they claimed, is to bring down industrial civilization. This is feasible, they further contended, because of the current system’s structural vulnerabilities, specifically, its dependence on fossil fuels. So, in a strategy that resembled the Earth Liberation Front a decade earlier, they urged activists to form secret cells to sabotage the energy infrastructure of today’s dominant and destructive social and economic systems. They also contended that activists should eschew pacifist ideologies and consider whether and when the time might be ripe to take up arms to overturn the system.

Since most of these strategies and points of view were articulated and practiced in the 1980s and 1990s, and the social and environmental conditions that gave rise to them have continued if not also intensified in most ways, in the coming years, we can expect periodic waves of radical environmental activism interspersed between relatively quiescent times, along with internal division, external suppression, and small and significant victories, all within an overall environmental landscape in which the global decline of biological and cultural diversity—, which gave rise to the movement in the first place—, continues to intensify.

This image, from a 1990 journal edition, communicates the persistent internal struggles regarding the priorities of Earth First! See Earth First! Journal 10, no. 8.

This image, from a 1990 journal edition, communicates the persistent internal struggles regarding the priorities of Earth First! See Earth First! Journal 10, no. 8.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Indeed, if the best predictor of future behavior is past behavior, the pages of Earth First! (found online since 2010) may well presage the future: by recounting the trials and tribulations, experimentation with tactics, internal divisions, and successes and failures, of a movement purporting to challenge what it considers to be the anthropocentric economic/political systems of industrial (and industrializing) societies. Examining the images it presents and the arguments its activists make, perusing the poetry it provides and perhaps finding environmental music online which has helped to inspire its activists, will provide a sense of the movement in a way that reading scholarly or journalistic articles about it cannot.

Although not all of the movement campaigns or divisions are discussed in the journal’s pages, its overall commitment to free speech and debate makes it an excellent primary source for understanding its internal disputes, its strengths, and weaknesses, its heroism and flaws. In the interest of free inquiry and debate, this valuable documentary archive is now available worldwide, for the first time, thanks to the Rachel Carson Center’s Environment & Society Portal.