Structures of Inequality

The former Chief Economist for the World Bank Lawrence Summers promoted a very liberal trade regime for hazardous waste. Illustration by Jonas Stuck, 2021.

The former Chief Economist for the World Bank Lawrence Summers promoted a very liberal trade regime for hazardous waste. Illustration by Jonas Stuck, 2021.

2021 Jonas Stuck

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Hazardous waste trade thrives on global economic inequalities while reinforcing social and ecological inequalities. An internal World Bank memo from 1991 by Lawrence H. Summers, at the time Chief Economist for the World Bank, revealed how “dirty industries” could actually profit from global inequalities. In line with the World Bank’s ethos of market liberalization, he suggested exporting polluting industries to what he called Least Developed Countries (LDCs). Summers highlighted the financial advantages of countries with lower wages. If toxicants affected workers negatively, damage for the global economy would be arguably smaller if it affected low-skilled ones and not those from the high-tech industry. “I think the economic logic behind dumping a load of toxic waste in the lowest wage country is impeccable,” wrote Summers. He also observed an unequal distribution of hazardous waste on a global scale that gave room to move waste from places of high population density, such as Los Angeles, to places of low population density, such as the Sahara: “I’ve always thought that under-populated countries in Africa are vastly UNDER-polluted.” And finally, he underlined the lower opportunity costs in LDCs: concerns over hazardous waste increasing the chance of getting cancer would be lower in countries with a high mortality rate among the young. Cancer treatment for people beyond their 50s and 60s is not as much of an issue if there is a critical number of citizens that do not ever reach that age.

For Summers and those supporting his arguments, his proposal was a thought experiment applying economic distribution logic to the global scale, hoping that in the end, this would lead to a general increase in economic output and improve welfare around the globe. You can have a look at The Economist article “Let Them Eat Pollution” in which they first published the leaked memo in March 1992 here. In fact, Summers’s logic of exporting hazardous waste sheds light on waste management practices that had been ongoing since the 1970s. Check out, for instance, Claudio de Majo’s short article on Italy’s Poison Ships dumping hazardous waste in Nigeria.

Not in my backyard: The globalization of local protests

Paradoxically, it was not only Chief Economists for the World Bank who were ready to sacrifice people and ecologies far away; some environmentalists were as well. Growing awareness and opposition built up exactly where most of the hazardous waste was (and still is) produced: in the Global North, with the United States being by far the biggest emitter. Long before the United States embarked on a global journey of “garbage imperialism,” a highly discriminating pattern of waste disposal had already been implemented within the country.

Hazardous waste sites often sparked local resistance with the slogan “Not In My Back Yard.” Illustration by Christian Mayer, 2021.

Hazardous waste sites often sparked local resistance with the slogan “Not In My Back Yard.” Illustration by Christian Mayer, 2021.

© 2021 Christian Mayer

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

A study from 1983 by the US Accounting Office found that three out of four hazardous waste dump sites in the southern states of the United States were situated near African-American communities—even though these communities made up only 20 percent of the entire population. The country’s policies for siting waste management facilities valued people’s lives according to their income and ethnic background. Native American and Black communities in particular had to bear the long-lasting toxic legacies of living close to incinerators or landfills. It is for this reason that some parts of the Mississippi River are also known as the “Cancer Alley.”

Such unequal geographies of pollution led to an increasingly strong environmental justice movement, which fought against this internal waste imperialism in the 1980s. The institutionalization of environmental politics and regulations triggered exploding disposal costs of hazardous wastes, from around $2.50 per ton in 1978 to around $200 in 1987 for landfilling in the United States. This increase in disposal prices also reflected the general distrust of environmental activists, concerned citizens, and politicians for disposal sites of hazardous waste. Existing landfills quickly reached their capacities and new ones could not be built because of local protests. Activists campaigned against the local disposal of harmful garbage—the slogan “Not in my backyard!” was born.

In order to get rid of their waste, municipalities and private companies in the Global North found a questionable solution by exporting waste to places not willing or able to protect their own “backyards.” The city of Philadelphia, for example, disposed of only very little of its own hazardous waste within city premises in the 1970s and 1980s, with the rest moved first beyond city, then state, and then international borders. First to New Jersey and Ohio, then to Panama, Haiti, or Guinea. Other municipalities and industries in the United States, West Germany, France, the UK, or Italy—to name just a few—started to export their hazardous waste too, for instance, to the Caribbean, Latin America, or West Africa. “Out of sight, out of mind” became a common mindset for hazardous waste management. In this context, Summers’s memo in the early 1990s was actually a reflection of a kind of racist and imperialist thinking that had already been put into action in the preceding decades.

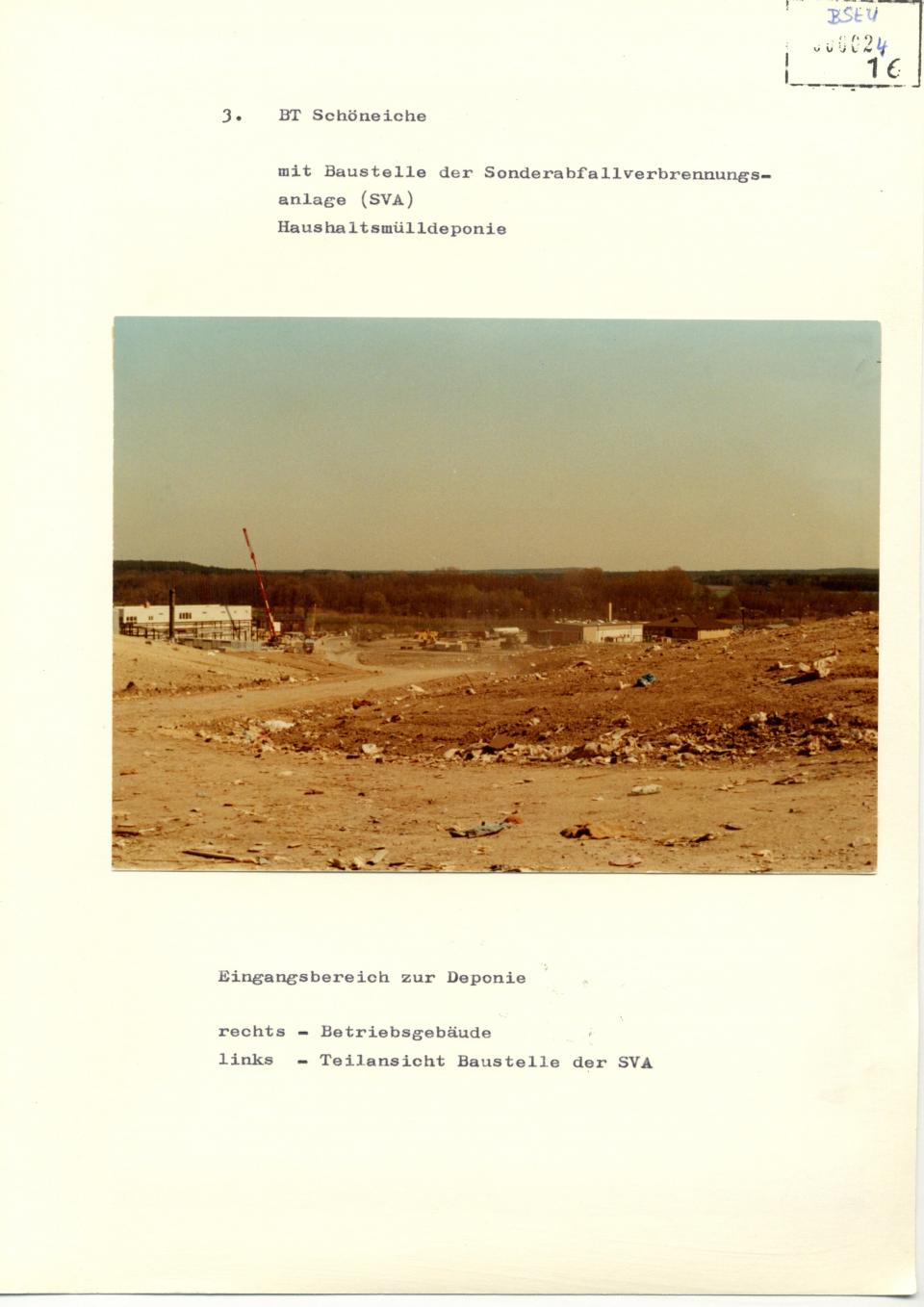

The pictures in this collection are from the Stasi Archive, documenting hazardous waste management in East Germany. This image shows the entry of the dump site Schöneiche and the construction site for a special waste incinerator, exclusively designed to incinerate Western waste.

The pictures in this collection are from the Stasi Archive, documenting hazardous waste management in East Germany. This image shows the entry of the dump site Schöneiche and the construction site for a special waste incinerator, exclusively designed to incinerate Western waste.

© BStU

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

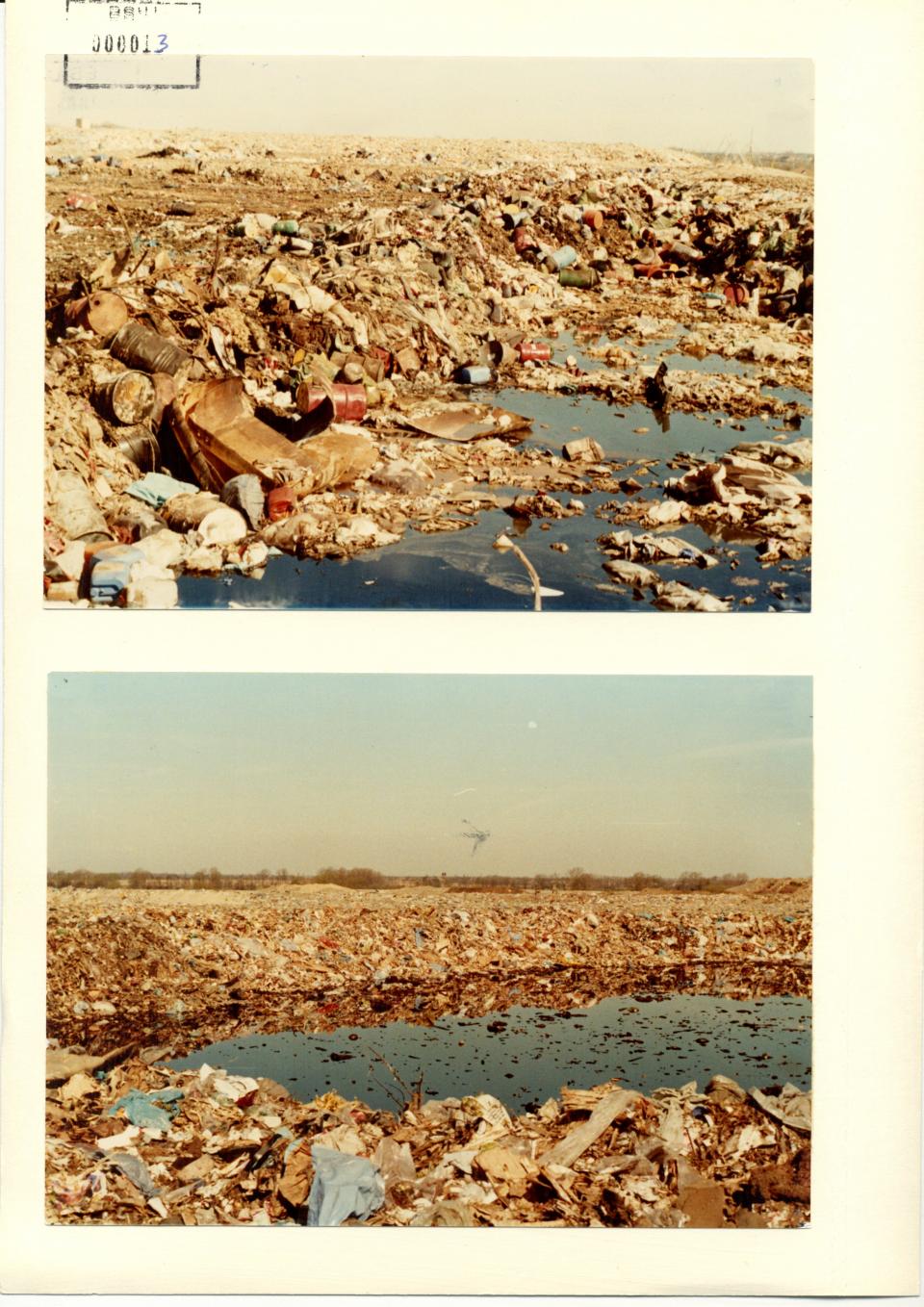

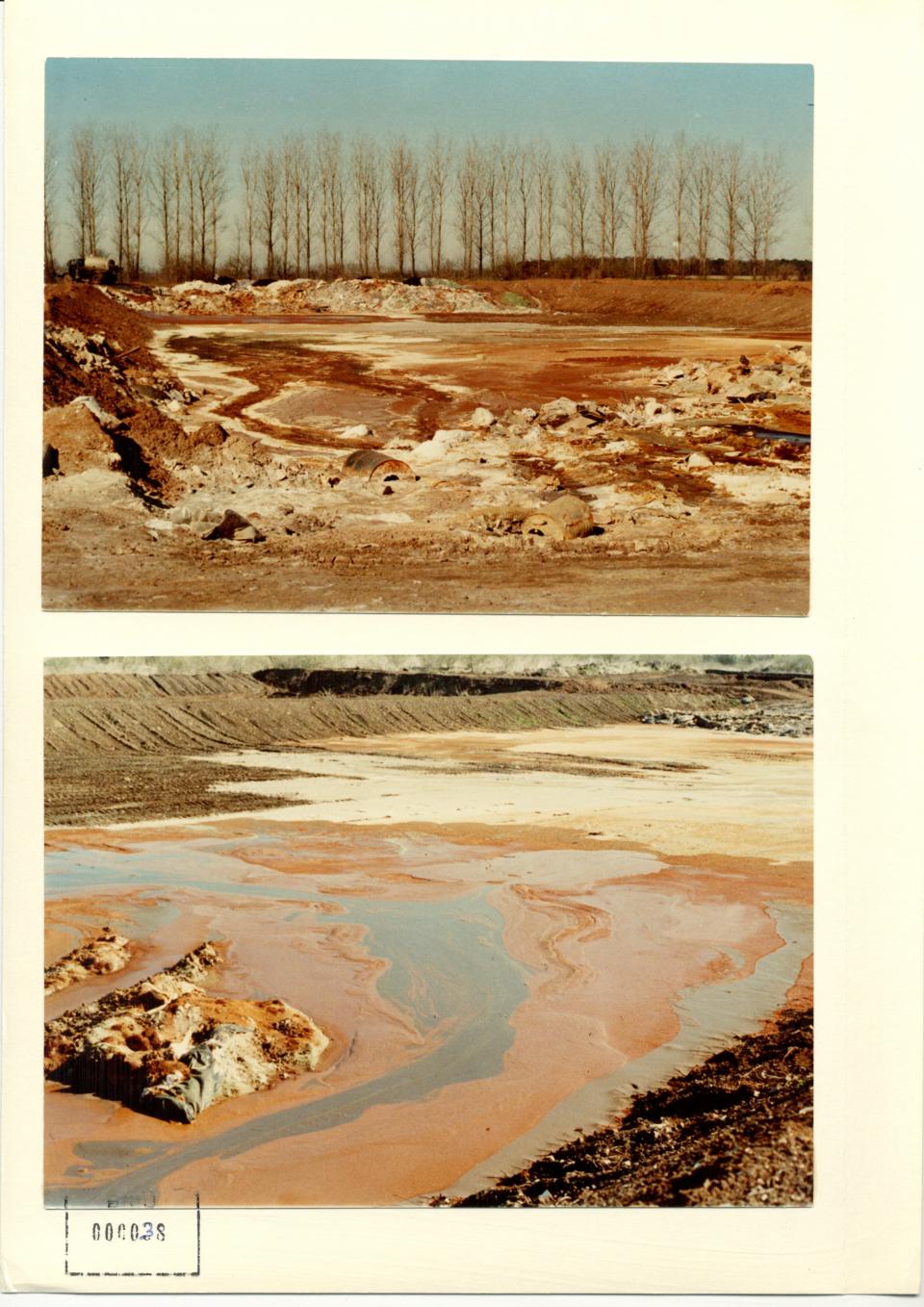

This waste pit in Vorketzin (located in former East Germany) was used to dump hazardous wastes such as used oils or paint mixed with regular household waste. Unknown photographer, c. 1988.

This waste pit in Vorketzin (located in former East Germany) was used to dump hazardous wastes such as used oils or paint mixed with regular household waste. Unknown photographer, c. 1988.

© BStU

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Double standards and waste trade

The environmental activism against new disposal sites in the Global North created a constellation in which countries with less rigid environmental regulations (often situated in the Global South), became a cheap alternative for disposal. Often, however, this business model looked promising for both sides. The exporting country saved money on the disposal costs of the hazardous materials and the importing country earned money or political influence by treating and recycling the incoming waste materials.

Before reunification, the two Germanys were a case in point. The import of Western trash to East Germany was responsible for around 10% of East Germany’s hard currency import. From 1986, West German environmental legislation clearly stated that waste export was only allowed if the disposal safety was guaranteed to be on the same level as West German standards. The West German government, however, could not monitor this requirement, as all environmental data in East Germany had been classified since 1982.

Notwithstanding, the West German state of Hesse, despite having an environmental minister of the Green Party, took the controversial decision to export its hazardous waste to Europe’s biggest hazardous waste landfill, Schönberg—conveniently located in East Germany. This waste dump was situated only five kilometers beyond the German-German border near the West German city of Lübeck. Lübeck’s citizens were afraid of the risks posed by the dumpsite. As the landfill did not have a base line, chemicals could get into the groundwater and travel below the border all the way to Lübeck. Spontaneous fires on the waste dump also threatened the quality of Lübeck’s air. Members of the Green Party and activists of the local citizens’ initiative protested against the double standards of the waste transports from Hesse to East Germany. The hazardous waste, which was too contentious to landfill within state boundaries, was shipped to East Germany under the Green Party’s minister Joschka Fischer. Fischer embodied the desperate position that the lack of disposal infrastructure in Western countries posed to politicians. In 1986, he famously ended an open letter to justify his decision with the words “best wishes from the middle of a shithole”—knowing that he could not resolve this disposal issue in an ethical manner and at the same time deal with the urgent pressure to dispose of the Hessian hazardous waste. Exporting the hazardous waste to the other side of the inner-German border appeared the only feasible solution to the waste piling up in Hesse.

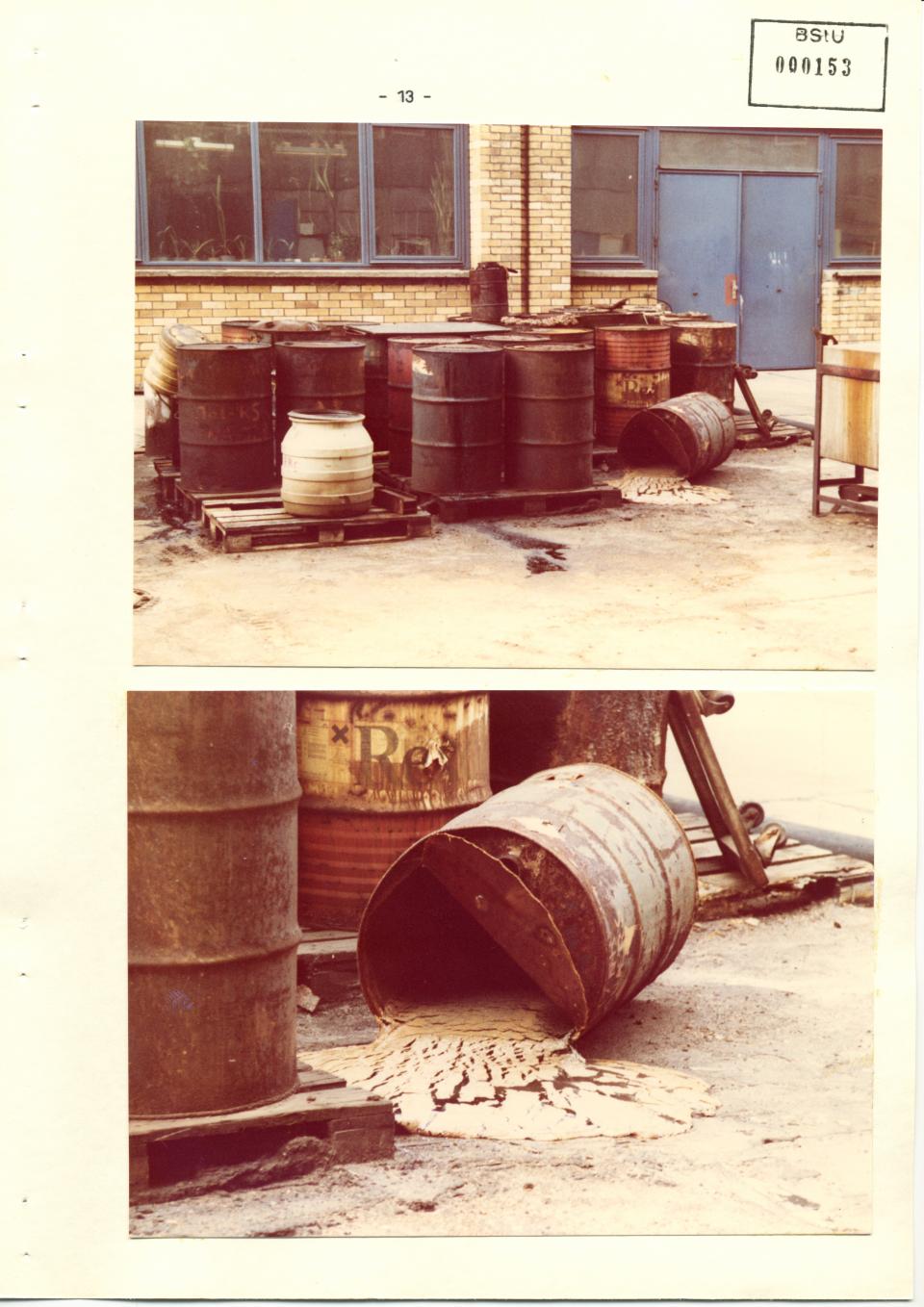

Oil sludge covers waste pits in Röthehof, a former hazardous waste dump for Berlin and Potsdam. Unknown photographer, c. 1988.

Oil sludge covers waste pits in Röthehof, a former hazardous waste dump for Berlin and Potsdam. Unknown photographer, c. 1988.

© BStU

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

For his PhD project, team member Jonas Stuck tried to uncover this history of waste shipments across the Iron Curtain. He visited regional and federal archives as well as the archive of the German Green Party, Greenpeace International, and the Stasi state security service of East Germany. This original effort to dig up the history of a business that went on behind closed doors for almost 20 years—from the early 1970s until the fall of the Wall—showcases the double standards that are often part of the decision making by the exporting countries.

Fighting for environmental justice

Summers’s memo caused a huge outcry. Economists of the 1990s thought that economic growth was the solution for environmental problems. Higher wages would not only lead to a higher demand for a “clean” environment but also create more financial resources to re-invest in environmental protection projects. They fell in line with what Indira Gandhi, the former Prime Minister of India, had already said at the United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in 1972, that poverty was the biggest polluter. In hindsight, this promise of salvation through economic growth was more a myth than a truth.

Environmental activists around the globe revealed that the hazardous waste trade was deeply rooted in (neo-)colonial patterns and exploited regional and global inequalities. Poor communities of color had to bear a vastly disproportionate burden of industrial activity. In the early 1990s, hazardous waste became an international symbol of contention between the Global South and industrial countries. To learn more about the power of waste, have a look at Simone Müller’s virtual exhibition on “The Life of Waste.”

In the 1990s, activism and the approval of environmental legislation, such as the Basel Convention, created frameworks which tried to work against the inequalities inherent in the global waste economy. Even though the legal regulations still have loopholes through which inequalities are reinforced, they proved to be one of the biggest signs of change. Environmental justice continues to work towards the principle that all people and communities are entitled to equal protection of environmental and public health laws and regulations.