Bathrooms and personal hygiene

Gumersindo Cuéllar Jiménez, Mujer junto a niña sentadas junto al río

Gumersindo Cuéllar Jiménez, Mujer junto a niña sentadas junto al río

A mother sits with her young daughter on the banks of a river, possibly the Bogotá River. They would not have suspected that decades later, their admiration for the beauty of the river would be replaced by feelings of disgust and fear towards the polluted stream.

All rights reserved. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Banco de la República de Colombia. Courtesy of Mario Cuéllar Bobadilla.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, serious health problems were common in the city of Bogotá. Public squares, markets, hospitals, and city streets were persistently filthy. One of the reasons for it was the design and the city’s location. Bogotá was built at the foot of nearby mountains and the streets were designed to carry sewage and garbage down their slopes through shallow, open-air gutters that ran down the center. Understandably, the streets tended to become water canals of rain and sewage, which, along with the local rivers and rivulets, collected filth and garbage as they flowed, so becoming channels for waterborne diseases.

This became a matter of great concern for the public and city officials. Physicians, engineers, and architects—influenced by European and North American hygienism—began to demand transformations of public and private spaces. Filth in the city was perceived as a source of, and breeding ground for, countless microbes, germs, and bacteria that posed serious threats to human health. To remedy this, hygiene programs were adopted to solve garbage and health problems within a framework of measures that aimed to modernize the city.

The urban hygiene movement of the Colombian physicians, engineers, and architects, just like the one in Europe and North America, did not question the condition of public spaces only; it also turned its attention to people’s homes. The living conditions in Bogotá that inspired so much criticism were directly related to municipal deficiencies in providing basic services such as running water, sewage management, and garbage disposal for low-income neighborhoods, whose streets were usually unpaved. These neighborhoods, called barrios obreros, were comprised of groups of houses that—despite their small size, poor lighting, and inadequate ventilation—were homes to large families who lived in cramped and unsanitary conditions. Many of these houses were actually huts with dirt floors, straw roofs, and only a single main living space whole families used for sleeping, eating, working, and often keeping animals.

Bathrooms were not a common feature in these kinds of houses, which sprang up along the periphery of the city. In the late nineteenth century that included the slopes of the Eastern Mountains, the unoccupied western side of the northern railroad tracks and to the south along the roads leading to what were then the towns of Usme and Bosa (which are today both incorporated as districts within the greater Bogotá area). Instead of proper bathrooms, makeshift holes or latrines excavated around the house were used by residents to relieve themselves. It was also common for people to resort to relieving themselves and disposing of their waste on the neighborhood streets, where it was expected that rainwater would eventually carry off the filth to the nearest sewers; these, in turn, would deposit the waste in the streams crossing the city.

The city’s rivers and rivulets thus became a multipurpose water network across the city that took away human waste from its point of origin, dispersing a foul stench throughout its course, and propagating infestation and diseases. Skin infections, typhoid fever, dysentery, gastroenteritis, hepatitis, and cholera, all of them to be contracted by ingesting contaminated water.

Concerns over the spread of diseases drove the experts’ attention to people’s personal hygiene, which was considered absent or inappropriate. To combat this, manuals, posters, and public service announcements were used to teach people satisfactory methods of washing their faces, hands and bodies. These public service announcements had an important predecessor in the well-known etiquette handbook “Manual of Urbanity and Good Manners for Young People of Both Sexes” (Manual de Urbanidad y Buenas Maneras para Uso de la Juventud de Ambos Sexos).

“Bodily cleanliness should play an important role in our daily routines and we must never cease to dedicate to it the time it requires of us, no matter how large our workplace or how numerous our tasks.

Just as we must never lay ourselves to sleep without first praising and thanking God for all he gives us, what could be considered a kind of spiritual cleaning, that cleanses the soul from the stains of daily passions, we must never lay on our beds without first cleansing our bodies. We do this not just for the satisfaction that cleanliness provides in itself but also so that we may be decently prepared for any happenstance that may occur in the middle of the night.

Upon waking we must do the same. After filling our spirits by dutifully praising God and asking for him to lead us in our day, we must clean our bodies even more carefully than we do before going to bed.

It may occur that on some occasions we may not be able to properly wash ourselves before going to bed, because of tiredness, sleepiness, or for whatever other circumstances common to the late hours that may impede us. Thus it is even more important that upon waking we never omit cleanliness from our routine. So we must wash our face, our eyes, our ears both inside and out, all around our neck etc. etc., we will then wash our heads and comb our hair.”

—Manuel Antonio Carreño. Manual de urbanidad y buenas maneras para uso de la juventud de ambos sexos; en el cual se encuentran las principales reglas de civilidad y etiqueta que deben observarse en las diversas situaciones sociales; precedido de un breve tratado sobre los deberes morales del hombre, 45-46. Bogotá: Editorial Voluntad, 1961. First edition: 1871. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

Written by the Venezuelan diplomat and teacher Manuel Antonio Carreño, this handbook became popular in Latin America upon its publication in New York in 1854. Issued for the first time in Bogotá in 1871, it influenced the daily behavior of citizens in private and public spaces where socializing took place. Personal hygiene was included in Carreño’s manual as an essential daily regimen for anyone wishing to stay healthy and to accomplish social prestige. According to Carreño, upon waking in the morning and before going to sleep at night, it was necessary to wash one’s face, eyes, ears, neck, and head. The hands should be washed several times a day, especially before eating, and the whole body should be washed at least once a week in a bath or shower.

Dirección Nacional de Salubridad, “El baño del niño: Normas generales para realizar esta tarea medular de la salud”, El Tiempo, December 19, 1946, 18

Dirección Nacional de Salubridad, “El baño del niño: Normas generales para realizar esta tarea medular de la salud”, El Tiempo, December 19, 1946, 18

Illustration in a newspaper article entitled The Child’s Bath: General Guidelines for this Fundamental Health Practice, written by the National Health Directorate in 1946. This illustration shows the method by which a mother should bathe her baby, and the increased number and quality of toiletries to use.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of El Tiempo Casa Editorial.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Guidelines for personal hygiene in these types of manuals were gradually adopted by families who managed to get copies of them, or whose children were taught its basic lessons in school. However, the most disseminated information came from public service announcements made by government agencies like the Directorate for Hygiene and Health of the Bogotá Municipality (Dirección de Higiene y Salubridad del Municipio de Bogotá). These announcements were meant to promote healthy habits and practices, and were adopted so as to mitigate the effects of infections and contagious illnesses. Physicians Manuel N. Lobo, Luis Zea Uribe, Cenón Solano, Tiberio Rojas and Pedro M. Ibáñez, who were linked to the Directorate for Hygiene and Health, made regular use of the monthly publications of the Municipal Hygiene Registry (Registro Municipal de Higiene) to disseminate information detailing how public bathrooms functioned, to recommend a length and temperature for baths and showers, and to educate people as to the importance of washing their hands in order to avoid contagious illnesses like typhoid fever.

Further instructional publications included manuals specifically targeting mothers, with information on infant health and cleanliness. Among these were the “Manual of Infant Hygiene and Medicine for Mothers” (Manual de Higiene y Medicina Infantil al Uso de las Madres de Familia), written by pediatrician José Ignacio Barberi, and published for a second time in 1905. It recommended that mothers bathe their children every day with warm water for no longer than five minutes. In part, this daily bathing routine was to ensure that the child’s pores would not be clogged by dirt since they helped eliminate toxins—much like exhalation and urination—and thus kept internal organs healthy.

“Bathing is, for me, such an essential element for good health that I have children bathe even when they have fevers, using baths as a kind of medicine. General concerns about bathing come from the fact that among us, it is associated with rivers or rainwater and therefore cold water. As I have stated before, bathing should be done with warm water to avoid any ill effects. If a child cannot sleep, bathe him before going to bed and he will sleep all night long. Compare a child who bathes regularly to one that does not, the clean child’s skin will be clean and terse in contrast to the rough and potted skin of the one that is not bathed regularly.

Bathing prevents infectious diseases and serves as a tonic for the body in general, it is medicinal with surprising positive effects for many ailments.”

—José Ignacio Barberi. Manual de higiene y medicina infantil al uso de las madres de familia, ó sea tratado práctico sobre el modo de criar á sus hijos y de atenderlos en sus enfermedades leves, 46-47. Bogotá: Imprenta Eléctrica, 1905. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

Babies requiring special care were to be washed with glycerin soap and a soft sponge in small tubs, with water heated to body temperature. Rainwater was recommended for these baths since the city’s water supply was not trusted to be potable. This type of instructional information for child hygiene was also included in newspaper and magazine articles such as the one published in 1946 by the National Health Directorate (Dirección Nacional de Salubridad) with the title “The Child’s Bath: General Guidelines for this Fundamental Health Practice” (El Baño del Niño: Normas Generales para Realizar esta Tarea Medular de la Salud). Using illustrations and a plain writing style, the National Health Directorate insisted that the child’s tub, soap, mineral oil, cotton balls, towels, and blankets never be used for anything other than bathing the child so as to avoid cross contamination. The article also gave mothers special tips for bathing newborn babies during their first week due to the tendency of soap and water to dry out their delicate skin.

“A daily bath—or better still, bathing twice a day—is one of the most powerful ways of preserving our youthful beauty. Taken in almost-boiling water like the Japanese, or in freezing water as some nature fanatics do, bathing is always a gratifying refuge for our fatigued bodies”.

—“Higiene y belleza.” Cromos, 18 March 1933, 6. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

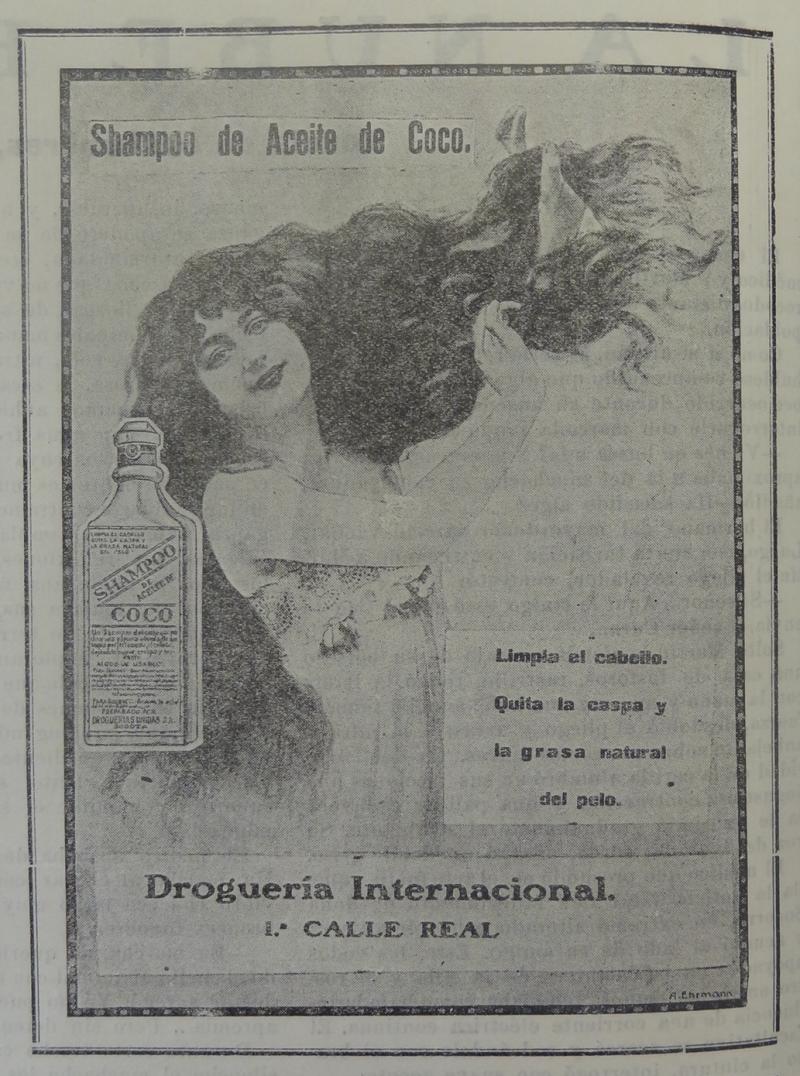

“Shampoo de aceite de coco”, Cromos, April 5, 1924, 250

“Shampoo de aceite de coco”, Cromos, April 5, 1924, 250

Advertisement for a coconut oil shampoo for cleansing the hair by removing dandruff and natural oils. In the early twentieth century body cleansing began to be perceived as a need rather than a privilege. Shampoos, soaps, and other cosmetic products advertised in newspapers and magazines were used together with water to eliminate dirt, oil and odor from hair and skin in favor of health and beauty.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Revista Cromos.

In the early twentieth century, when bathing became an increasingly popular practice among Bogotá citizens, bathing was associated with certain health benefits and risks. Perceived health risks associated with long hot baths such as tiredness, heart problems, and dry skin waned within decades as people started following guidelines given by doctors. Bathing gradually became an essential daily practice because it helped to keep people healthy and also facilitated the feeling of being young and beautiful on account of the resulting moisturized, softened, and clean skin. The cosmetic aspects of bathing quickly inspired advertisements for related products such as soaps, shampoos, bath salts, skin tonics, deodorants, and perfumes, all of which complemented the cleansing effects of water. These products, now basic elements in daily hygiene regimens, quickly became staple consumer goods for all families.

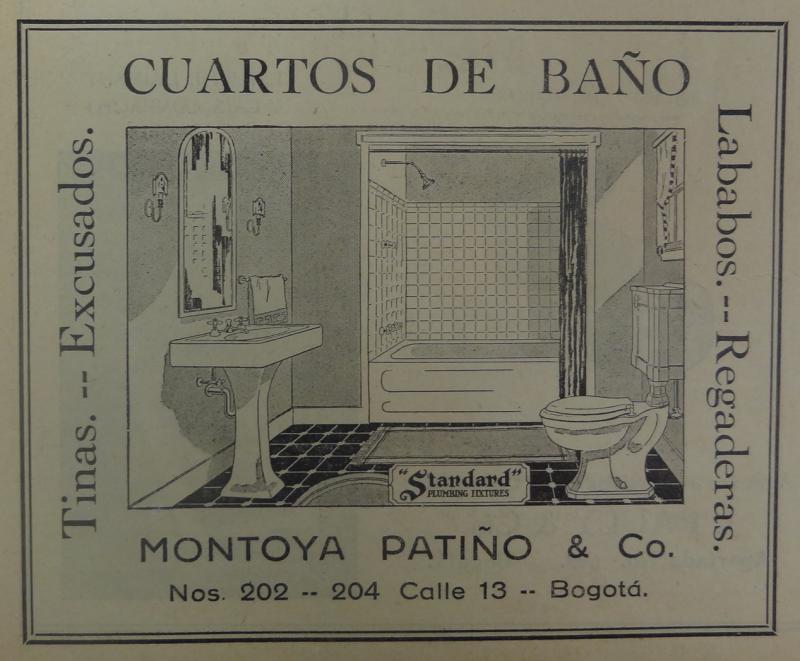

With bathing established as a daily practice, proper bathrooms became essential domestic spaces that provided adequately hygienic conditions along with comfort and privacy. Modern bathrooms had characteristic features such as floors made of easily washable materials, cement walls that were waterproofed using lime plaster, oil-based paint, and ceramic tiles. They also included fixtures like bathtubs, showers, hand sinks, toilets, and bidets. All of these features permitted the easy disposal of human waste and hygienic washing by taking advantage of running water from pipes connected to the municipal aqueduct and sewage drains.

“Cuartos de baño”, Cromos, December 13, 1930, 31

“Cuartos de baño”, Cromos, December 13, 1930, 31

Advertisement for Montoya Patiño and Co., a company selling bathtubs, toilets, sinks and showers for completely hygienic bathrooms. Having bathrooms inside homes bolstered the ongoing domestication of water in the city, but also became evidence of the socially differentiated relationship between people and water, as not everyone could afford to have one.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Revista Cromos.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

However, modern bathrooms like these were absent from most Bogotá homes until the mid-twentieth century. Those houses built in the colonial period or the early Republican years did not include bathrooms in their architecture, and nor were bathrooms built in more recently constructed homes because of the owners’ economic restrictions. It was not until the second decade of the twentieth century that municipal officials, private developers, and workers’ cooperatives began building housing projects with bathrooms, regardless of the socioeconomic status of the neighborhoods in which they were located.

Having bathrooms inside homes bolstered the ongoing domestication of water in the city. This correlated both with the desire for modern health practices and new conceptions of bodily cleanliness as a discreet and private routine. The domestication of water meant that most of the city’s inhabitants no longer had to use the local rivers or collect rainwater for bathing: water was now available from the municipal aqueducts and pumped into homes through pipes directly into faucets for showers, bathtubs, and sinks. People only needed to turn on a faucet and water would pour with a steady, adjustable, and continuous flow all year round. This new approach to water use not only increased the amount of water demanded, used, misused, and polluted, but also demonstrated how humans could sometimes control what had previously been subject to natural cycles, even though nature never became a passive actor completely submitted to human will.

Despite the increasing use of bathrooms in private homes, some people could not afford the costs to build one and had to rely on showers and tubs in public bathhouses. These public washrooms were regulated according to standards set out by municipal authorities. On 30 April 1915, the Bogotá City Council (Concejo de Bogotá) approved a proposal made by the Directorate for Hygiene and Health to draw basic regulations for public bathroom services, which until then were being offered in inadequate and rudimentary facilities that indeed increased the risk of disease propagation. The new regulations stipulated that public bathroom facilities had to be spacious and clean—meaning washable cement walls, paved floors with drains, and doors and windows constructed so as to prevent strong cold breezes coming from outside. Furthermore, any business owner wishing to operate a public bathhouse had to hire employees to sanitize tubs before clients’ use, and were obliged to provide them with towels.

“Without counting the bathrooms in private homes, whose use is correct from the point of view of private hygiene and which are almost exclusively used by the city’s moneyed classes, Bogotá has no other public bath and washrooms than the waters from the Tunjuelo River and distant Bogotá River, the Fucha River which receives all of the runoff from the San Cristóbal hamlet, the scarce water from the Arzobispo stream, and the rivulets that cross the Chapinero neighborhood that are just as tainted as the waters from the Fucha River.

Various private companies have bathroom services for the public, although they are insufficient for public demand. These have yet to adopt the level of cleanliness, comfort, and affordability found in other cities. The showers and faucets are well established.

Workers and their families are excluded from these public bathrooms because they lack the means to afford them. From this stems the generally disheveled state of our poorer classes who never get the opportunity to use a bathroom unless misfortune lands them in hospital, jail, or better fortune lands them in barracks.”

—Tiberio Rojas and Pedro M. Ibáñez. “Contribución al estudio de la higiene pública de Bogotá.” Registro Municipal de Higiene, 20 July 1919, 15–16. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

Public bathrooms, however, were scarce and pricey for the general public. In 1919, physicians Tiberio Rojas and Pedro M. Ibáñez claimed that public bathrooms benefited only wealthy citizens, while poor people continued to rely on natural but often contaminated water from local currents—including the Bogotá, Tunjuelo and Fucha Rivers, and rivulets such as La Vieja and Las Delicias. The Bogotá City Council addressed the problem by approving its Accord No. 11 of 1919, which gave the Board of Relief (Junta de Socorros) a permit to build public bathrooms in new areas using city funds. Nevertheless, this utility never coupled with the population growth, and in 1936 the City Council ordered the construction of 26 new public bathhouses, which were designed like kiosks and located near public squares and open to all.

To view the caption and the source information, please click on the i in the upper left part of the image.

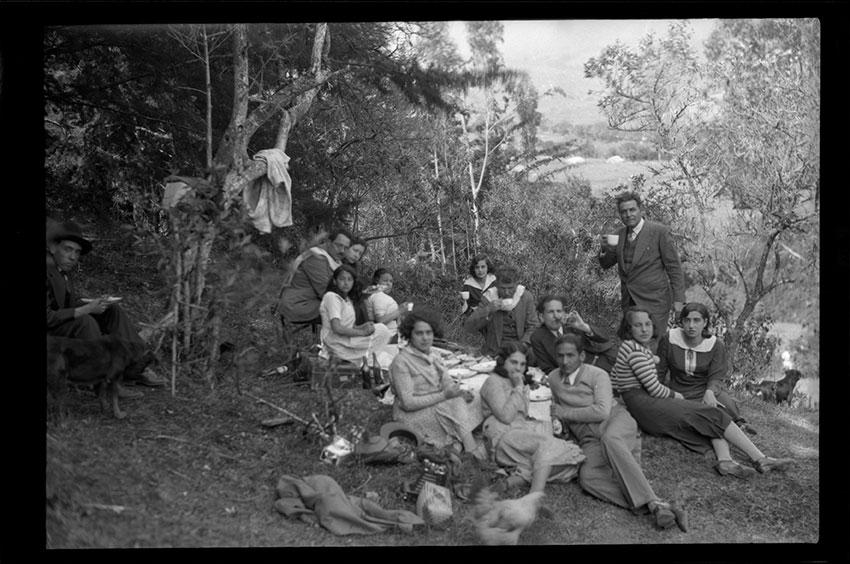

Group of people enjoying a picnic in the countryside. A small stream at the lower right of the photograph reminds us that riverside landscapes were places to enjoy recreational activities, before the rivers themselves were consumed by the urban expansion of Bogotá over the western savannah.

Source: Bogotá, Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Virtual Library, Collection Gumersindo Cuéllar Jiménez, Reference FT1726.

All rights reserved. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Banco de la República de Colombia. Courtesy of Mario Cuéllar Bobadilla.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

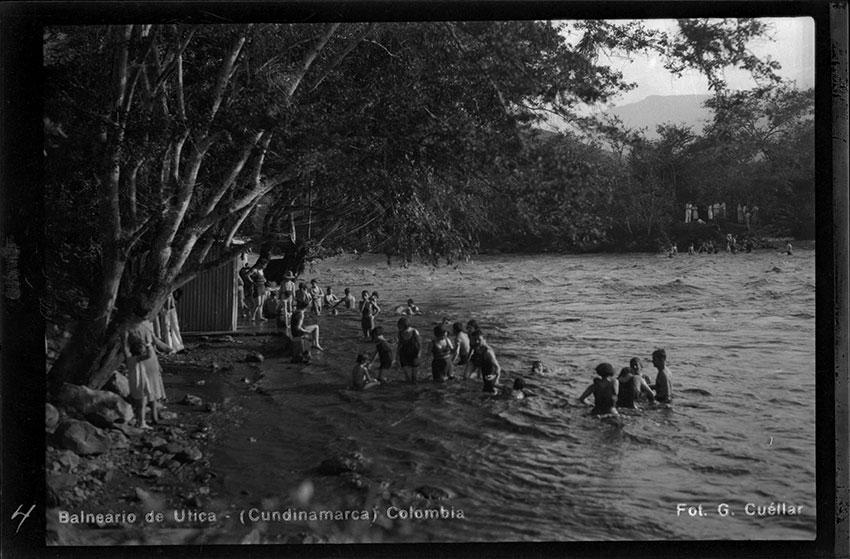

Group of people swimming in a natural pool formed by water from a river in Útica (497 m. above sea level), a temperate town located 119 kilometers from Bogotá (2640 m. above sea level) on the route down the mountains to the Magdalena River.

Source: Bogotá, Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Virtual Library, Collection Gumersindo Cuéllar Jiménez, Reference FT1736 brblaa1042991-4.

All rights reserved. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Banco de la República de Colombia. Courtesy of Mario Cuéllar Bobadilla.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

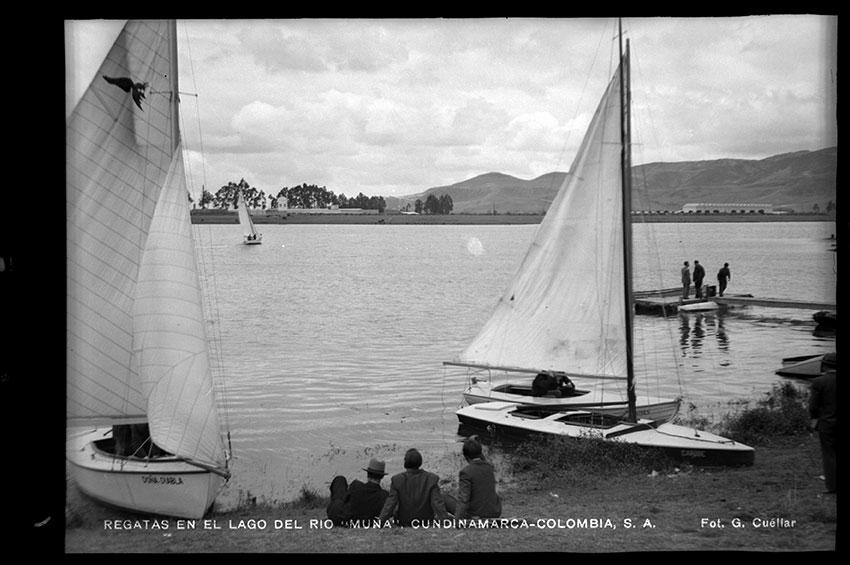

An example of watersports associated with recreational activities around rivers and lakes, this picture shows regattas sailing in the artificial lake formed by the Muña Dam, located south of Bogotá and used since the 1940s for hydropower generation.

Source: Bogotá, Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango, Virtual Library, Collection Gumersindo Cuéllar Jiménez, Reference FT1724 brblaa925921-4.

All rights reserved. Biblioteca Luis Ángel Arango. Banco de la República de Colombia. Courtesy of Mario Cuéllar Bobadilla.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Bathing in rivers continued, however, remaining a long-held custom for people regardless of their socioeconomic background. Those who no longer needed rivers for personal hygiene still enjoyed rivers as recreational zones. It was common for Bogotá families to take trips on weekends or holidays to nearby rivers and natural pools on the Bogotá Savanna, or those located in the warm climates of towns along the route down the mountains to the Magdalena River. These trips to rural areas outside the city were ideal opportunities to enjoy picnics on grassy pastures, sometimes stopping along the riverbanks to stare at the tranquil flow of water or engaging themselves in watersports and refreshing swims.

The shifting use of rivers from bathing to recreational activities shifted the perception of water into a source of entertainment, and reinforced the bucolic idea of the countryside as a contrast to the dirty and restless city streets. Around the mid-twentieth century these family trips to nearby rivers began to disappear from the repertoire of common Bogotá customs as the city itself began to expand into the surrounding wetlands and rural savanna. Wetlands dried out, fertile farmland was covered by construction, and some of the nearby rivers used for recreation were absorbed into the new urban landscape. Such was the case of the Fucha, Tunjuelo, and Bogotá rivers: once perceived as sites of leisure and contemplation, they were transformed throughout the twentieth century into streams that ran through the city, receiving wastewater discharges, and often flooding the neighborhoods next to their courses during rainy seasons.

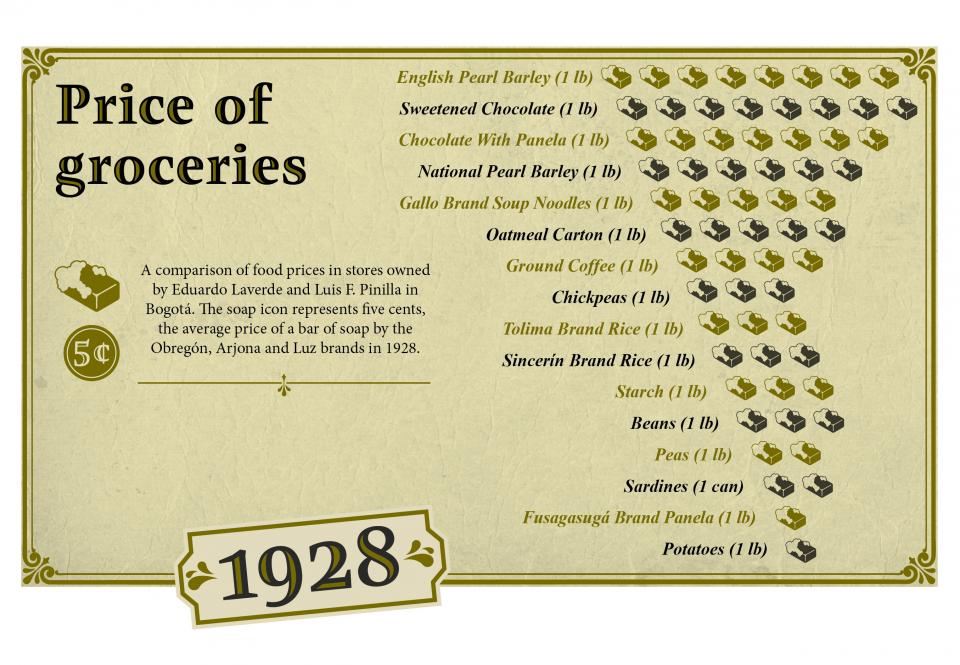

The price of groceries: Bars of soap at your fingertips

On 19 June 1928, the El Tiempo newspaper published a public service announcement that included the prices of goods and foodstuffs sold in the stores owned by Eduardo Laverde and Luis F. Pinilla that were located in Bogotá. This list demonstrates the importance of certain foodstuffs such as barley, oats, rice, potatoes, beans, peas, chickpeas, chocolate, coffee, sugar, and panela—solid blocks of sugar made from unrefined sugar cane juice—in Bogotá homes. It also enabled people to compare the price of a bar of soap to common foodstuffs as a means of demonstrating its affordability: for example, one bar of soap could cost 5 cents while a pound of sweetened chocolate could reach as much as 40 cents.

Easy access to cosmetic soaps towards the end of the 1920s shows how widely spread personal hygiene practices had become in Bogotá. Bathing had shifted from being perceived as an extravagant and distinguished exercise, exclusive to high society, to a routine practice for working-class people interested in staying healthy, clean, and attractive.

Price of groceries, 1928

Infographic showing a comparison of the price of cosmetic soaps with the price of several groceries in 1928.

“Precio de los víveres”, El Tiempo, June 19, 1928, 8.

Price of groceries, 1928

Infographic showing a comparison of the price of cosmetic soaps with the price of several groceries in 1928.

“Precio de los víveres”, El Tiempo, June 19, 1928, 8.

Created by Mónica Páez Pérez and María José Castillo Ortega. Tangrama, 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Regulations for hygienic buildings as spatial projections of hygienic discourse

Homes with bathrooms began to appear in large numbers in Bogotá during the second decade of the twentieth century. These new buildings were regulated by normative standards meant to promote the construction and maintenance of hygienic homes. Among these were: Accord No. 10 of 1902 released by the Bogotá City Council, Accord No. 40 of 1918 by the Central Board of Hygiene (Junta Central de Higiene), and Resolve No. 16 of 1919 by the National Health Directorate (Dirección Nacional de Higiene).

These building standards defined architectural requirements that homes in modern residential neighborhoods had to fulfil, and also tried to mitigate health problems caused by unhygienic conditions within homes in working-class neighborhoods on the peripheries. Poorer neighborhoods like the Paseo Bolívar—which was located on the slopes of the Eastern Mountains—were known to be unsanitary and precariously constructed. Homes, which were more like shacks, had no public utilities, were notoriously cramped, lacked separate living spaces, suffered from poor lighting and ventilation, were usually built from low quality materials, and had no bathroom at all.

After years of unsuccessful proposals, the city authorities finally decided to demolish the homes of the Paseo Bolívar as part of a sanitation project led by the Viennese urban planner Karl Brunner, who in 1933 had been named chief of the brand new Department of Urban Planning for Bogotá (Departamento de Urbanismo de Bogotá) after his successful experience as an urban planner in Santiago de Chile. His mission was to plan future urban development based on legislation, focusing on urbanization and road construction. The Department of Urban Planning for Bogotá compiled and published norms for hygienic buildings while also proposing building plans for working-class housing that conformed to hygienic building codes, thereby increasing the living standards of inhabitants.

Comparing an average home in the unplanned Paseo Bolívar neighborhood in the 1920s with one of the planned working-class neighborhood proposed by the Department of Urban Planning for Bogotá in the 1930s, enabled consideration of the differences between building standards in the two timeframes, and the role of homes like spatial projection of hygienic discourse.

Working-class housing: Reality and projection

The original virtual exhibition features a pretzi-presentation showcasing working-class housing in Bogotá: Reality and projection. View the presentation here. We have attached a transcript of the presentation to this archival version.

Please click on this image to start the presentation on working-class housing.

Architectural renderings designed by William Sarria Calderón. 2013.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.