Alfred Wegener’s Greenland Diaries

Alfred Wegener’s Scientific Work in Greenland

Alfred Wegener embarked on four Greenland expeditions between 1906 and 1931, a time when the conquest of the North and South Pole began to enjoy enormous international public attention. Within this so-called “heroic phase” of polar exploration, Wegener embodied a new type of polar explorer in that he was mainly interested in basic geoscientific and meteorological questions and that he introduced new scientific methods and instruments in the field of polar science. Aside from investigating unresolved geographic and cartographic questions with the intention of filling the last blank spots on Greenland’s map, Wegener’s work focused on gaining detailed knowledge about the origins of Greenland’s weather and climate conditions, the dynamics of its ice sheet, and the atmosphere above the Greenland ice sheet.

The exploration of Greenland during this period was also marked by the prospect of future transatlantic flights between North America and Europe. For meteorological phenomena such as the low-pressure zone in the North Atlantic and Johannes Georgi’s discovery of the jet stream over Iceland in 1926–1927 made it clear that Greenland had a significant influence on the development of weather patterns. Some of Wegener’s approaches, especially the exploration of the climatic and glaciological conditions as well as the use of seismological methodology to analyze the ice sheet, were continued after 1945.

Alfred Wegener (to the right) and Gustav Thostrup (1877–1955), second officer of the Danmark. Unknown photographer, 1906–1908.

Alfred Wegener (to the right) and Gustav Thostrup (1877–1955), second officer of the Danmark. Unknown photographer, 1906–1908.

Originally published in Achton Friis, Im Grönlandeis mit Mylius-Erichsen: Die Danmark-Expedition 1906–1908 (Leipzig: Otto Spamer, 1910: 351).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The last picture of Alfred Wegener. Alfred Wegener and his Greenlandic attendant Rasmus Willumsen shortly before the departure from “Eismitte” on Wegener’s fiftieth birthday on 1 November 1930. Photograph by Johannes Georgi, 1930.

The last picture of Alfred Wegener. Alfred Wegener and his Greenlandic attendant Rasmus Willumsen shortly before the departure from “Eismitte” on Wegener’s fiftieth birthday on 1 November 1930. Photograph by Johannes Georgi, 1930.

Courtesy of Alfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung (AWI). Signatur: NL 3 F Nr. 19.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Characteristic for this type of exploration was the enormous physical and psychological exertion that extreme weather conditions demanded. As a result, modern polar explorers like Wegener fell back on the traditional knowledge of the Inuit—including traveling by dog sled, wearing traditional Inuit clothes, building igloos, and hunting—in order to survive, work, and explore on the Greenland ice sheet over a longer period of time. Especially the crossing of Greenland and the establishment of a permanent research station in central parts of the Greenland ice sheet were difficult challenges at a time when new modes of motorized transport and flight began to be introduced in polar research.

Why Keep a Diary?

It is strange what unimportant things one includes in a diary here. But it is significant. If I report everything that I’ve done on a given day, it is a sort of justification. It is a triumph that I have been successful in occupying myself on a practical level. At the same time, I don’t believe that my diary is particularly enjoyable to read. For me, this expedition is surely very valuable. While before, I did have a certain type of energy, which here, for the purpose of comparison, I must call “moral energy.” Here, I am learning practical energy, the energy of activity. All these things that seem so unimportant, for example washing ourselves daily, overcoming an obstacle, irrelevant of what exactly it is—all these small things that make up daily life are things from which you can learn what “practical energy” is.

—Danmark Expedition, 15 September 1906, DMA NL 001/005, 130.

It is hard for me to find anything to do here in the tent. Books and instruments are all packed into boxes, and I cannot access them. The only reading material I have is Koch’s diary, which he kindly gave to me for this purpose. For a vagabond like me, there is no lack of small tasks, but when one has nothing else to do for the entire day, there is a time when the tent has been swept, petroleum has been poured onto the oven, a new light has been put up, all pipes have been filled and are hanging from the ceiling of the tent; when the horses have been fed and the hay for their next meal has been weighed; when one has read Koch’s diary: then, when one has nothing to do, one sits down and writes such a verbose, such a boring diary that no one will really want to read it.

—Danish North Greenland Expedition, 20 September 1912, DMA NL 001/009, 17.

Wegener’s expedition diaries encompass the Danish Danmark Expedition (1906–1908), in which he participated at the age of 26 as an expert for aerology, the Danish North Greenland Expedition together with Johann Peter Koch (1912–1913), which aimed to explore the Greenland ice sheet, and the Wegener-led German Greenland Expedition (1930–1931).

Today, these diaries allow us to reconstruct the course of an expedition from within. They provide insight into:

- Scientific questions: Methods, observations, measurements, the use of scientific instruments such as kites, balloons, and scientific photography.

- Everyday life on the expedition: progression of events, difficulties, successes.

- Polar technology: survival skills, strategies, mastering everyday challenges, the cold, nutrition, hunting, transport and logistics, dog sleds, ponies, and propeller sleds.

- A subjective dimension of experience: plans for the future, progression of the expedition, moods, sensitivities, conflicts with other expedition participants.

- A subjective perception of nature: aesthetic experiences and the limits of physical and mental capacities brought about by the cold, ice, snow, and the long polar nights.

Alfred Wegener during his second expedition to Greenland. Unknown photographer, 1912–1913.

Alfred Wegener during his second expedition to Greenland. Unknown photographer, 1912–1913.

Originally published in Johann Peter Koch, Durch die weiße Wüste: Die dänische Forschungsreise quer durch Grönland 1912/13 (Berlin: Springer, 1919: 125).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

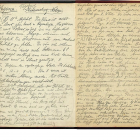

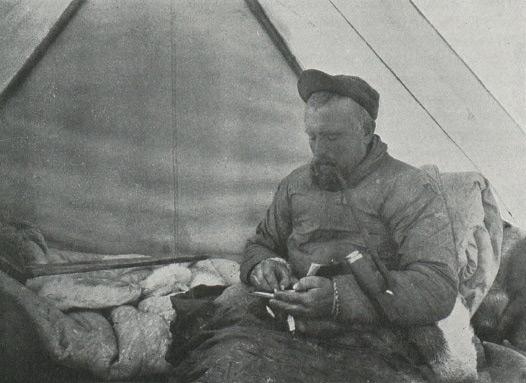

Expedition leader Johann Peter Koch, writing in his diary. Unknown photographer, 1912–1913.

Expedition leader Johann Peter Koch, writing in his diary. Unknown photographer, 1912–1913.

Originally published in Johann Peter Koch, Durch die weiße Wüste: Die dänische Forschungsreise quer durch Grönland 1912/13 (Berlin: Springer 1919: 62).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Writing diaries was an integral part of polar expeditions and Wegener was an obsessive diarist. For him, keeping a diary during his polar expeditions fulfilled several functions. A diary, for one thing, kept track of the course of the expeditions and served as a basis for further scientific and popular publications and narrations. It helped him organize and reflect upon daily experiences, and was a place where he could document natural phenomena and observations. For scientists and explorers, writing diaries provided a vital, existential function in relation to their experience in extreme (and often potentially deadly) environmental conditions. It allowed the explorer to maintain a sense of self and acted as a welcome distraction in a threatening and hostile environment. Wegener’s diaries additionally provide a backdrop for and a supplement to his scientific publications. Aside from lists of transported goods, measurements, and tables of instrumental observations, Wegener added small sketches of landscapes and descriptions of natural phenomena.

Furthermore, he documented everyday challenges and obstacles of obtaining scientific measurements, necessary improvisations, problems with other expedition participants, his own psychological and physical condition—all things that are not included in his scientific publications. Particularly noticeable is the uncertainty that Wegener felt regarding his role as a scientist as part of a thirty-man Danish expedition 1906–1908. Many times, Wegener references future plans for a South Polar expedition—a surprising find, given the common identification of Wegener as a Greenland researcher.

At the margins of inland ice sheets at Queen Louise Land. Unknown photographer, 1906–1908.

At the margins of inland ice sheets at Queen Louise Land. Unknown photographer, 1906–1908.

Originally published in Achton Friis, Im Grönlandeis mit Mylius-Erichsen: Die Danmark-Expedition 1906–1908 (Leipzig: Otto Spamer, 1910: 570).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

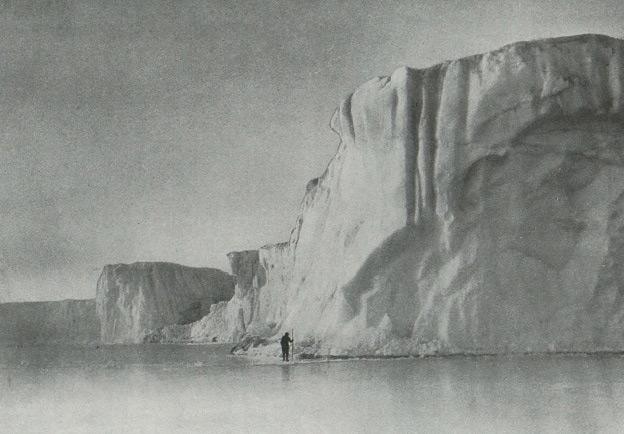

Ice wall in Greenland. Unknown photographer, 1912–1913.

Ice wall in Greenland. Unknown photographer, 1912–1913.

Originally published in Johann Peter Koch, Durch die weiße Wüste: Die dänische Forschungsreise quer durch Grönland 1912/13 (Berlin: Springer, 1919: 210).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

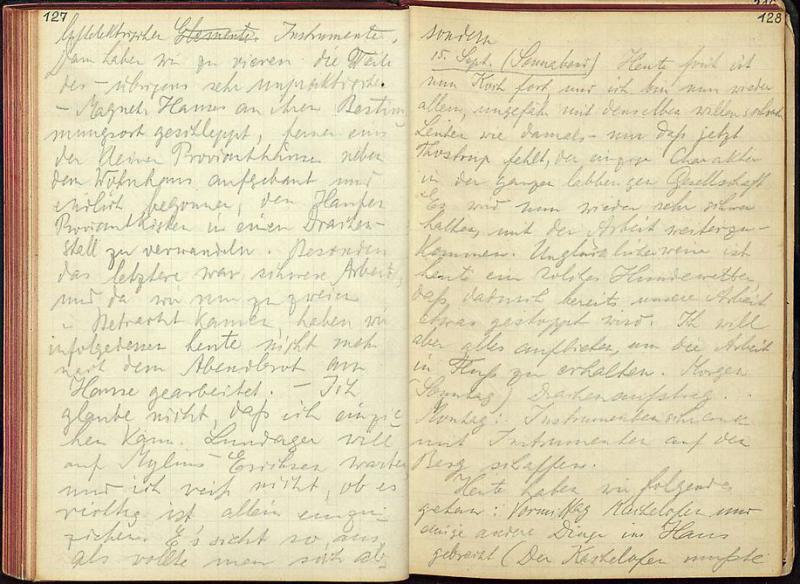

Due to the fact that Wegener lived in many places throughout his life, his estate is dispersed throughout many different places, including Berlin, Merseburg, Rheinsberg, Neurupin, Kopenhagen, Marburg, Graz, Vienna, Munich, and Bremerhaven. However, the majority of his original diaries, which form the basis of this online edition, are held by the Deutsches Museum in Munich. Munich’s diary collection encompasses fourteen volumes with a total of 2,200 small pages, twenty-two by eighteen centimeters, in oilcloth binding. There are indications in the diaries that some pages were ripped out. Overall, the diaries are written in easily legible handwriting that is partially in pencil, partially in ink; those originally in pencil were sometimes retroactively retraced in ink, probably in order to improve the legibility of the prose. At various points, there are red markings in the margin, and some sentences are crossed out in ink, making them entirely illegible.

At the same time, the various stages of diary writing indicate the use of the diary in some of Wegener’s later publications, or the edition of his diaries by his wife, Else Wegener. However, her edition was purposely shortened and the word choice was often changed. Johannes Georgi heavily criticized her in a lengthy article in the journal Polarforschung, not least based on the tense relationship between him and Wegener’s family, who had blamed him, in part, for Wegener’s death.

Propeller sleds and expedition members at the grave of Alfred Wegener. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Propeller sleds and expedition members at the grave of Alfred Wegener. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Originally published in Johannes Georgi, Im Eis vergraben: Erlebnisse auf Station „Eismitte“ der letzten Grönlandexpedition Alfred Wegeners 5th ed. (Munich: Müller, 1938: 226).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Further Reading

Demhardt, Imre Josef. “Alfred Wegener’s Hypothesis on Continental Drift and Its Discussion in Petermanns Geographische Mitteilungen (1912–1942).” Polarforschung 75 (2005): 29–35.

Georgi, Johannes. Im Eis vergraben. Erlebnisse auf Station “Eismitte” der letzten Grönland-Expedition Alfred Wegeners 1930–1931. Leipzig: Brockhaus, 1955.

Greene, Mott T. “Alfred Wegener.” Social Research 51, no. 3 (1984): 739–61.

Günzel, Hermann. Alfred Wegener und sein meteorologisches Tagebuch der Grönland-Expedition 1906–1908. Marburg: Universitätsbibliothek Marburg, 1991.

Jacobshagen, Volker. Alfred Wegener—1880–1930—Leben und Werk: Ausstellung anläßlich der 100. Wiederkehr seines Geburtstages. Berlin: Reimer, 1980.

Koch, Johann-Peter. Durch die weiße Wüste: Die dänische Forschungsreise quer durch Nordgrönland 1912–13. German edition prepared by Alfred Wegener. Berlin: Springer, 1919.

Körber, Hans-Günther. Alfred Wegener. Leipzig: Teubner, 1980.

Krause, Reinhard A., Eberhard Schindler, Rainer Brocke, Rolf Schroeder, and Volker Wilde. “Alfred Wegener—Vordenker und Erneuerer der Geowissenschaften: 100 Jahre Hypothese von der Drift der Kontinente.” Senckenberg: Natur, Forschung, Museum 142, no. 1/2 (2012): 12–17.

Krause, Reinhard A. “Alfred Wegener, Geowissenschaftler aus Leidenschaft: eine Reflexion anlässlich des 125. Geburtstages des Schöpfers der Kontinentalverschiebungstheorie.” Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv 28 (2005): 299–326.

Krause, Reinhard A., Günther Schönharting, and Jörn Thiede. “Introduction to content, meaning and origins of the book “Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane” von Alfred Wegener (1880–1930).” In Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane, edited by Alfred Wegener. Reprint of 1st and 4th edition. Stuttgart: Borntraeger, 2005.

Lüdecke, Cornelia. “Der Meteorologe Alfred Wegener.” Naturwissenschaftliche Rundschau 60, no. 3 (2007): 125–28.

Lüdecke, Cornelia. Die deutsche Polarforschung seit der Jahrhundertwende und der Einfluss Erich von Drygalskis. Bremerhaven: Alfred-Wegener-Institut für Polar- und Meeresforschung, 1995.

McCoy, Roger. Ending in Ice: The Revolutionary Idea and Tragic Expedition of Alfred Wegener. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006.

Oreskes, Naomi. The Rejection of Continental Drift: Theory and Method in American Earth Science. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999.

Ries, Christopher J. “Armchairs, Dogsleds, Ships, and Airplanes. Field Access, Scientific Credibility, and Geological Mapping in Northern and North-Eastern Greenland 1900–1939.” In Scientists and Scholars in the Field. Studies in the History of Fieldwork and Expeditions, edited by Kristian H. Nielsen et.al., 329–61. Aarhus: Aarhus Universitet, 2012.

Schwarzbach, Martin. Alfred Wegener und die Drift der Kontinente. 2nd rev. ed. Stuttgart: Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft, 1989.

Schwarzbach, Martin. Alfred Wegener—The Father of Continental Drift. With an introduction to the English edition by Anthony Hallam. Madison: Science Tech, 1986.

Wegener, Alfred. Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane. 4th ed. Braunschweig: Friedrich Vieweg & Sohn Akt. Ges., 1929. Online edition

Wegener, Alfred. Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane. Reprint of the 1st (1915) and 4th edition (1929), edited by Reinhard A. Krause. Stuttgart: Borntraeger, 2005,

Wegener, Alfred. The Origin of Continents and Oceans. Translated by John Biram. Mineola: Dover Publications, 1966.

Wegener, Alfred. Thermodynamik der Atmosphäre. Leipzig: Verlag Johann Ambrosius Barth, 1911.

Wegener, Else, ed. Greenland Journey: The Story of Wegener’s German Expedition in 1930–31, as Told by Members of the Expedition and the Leader’s Diary. Translated by Winifred M. Deans. Glasgow: Blackie & Son, 1939.

Wegener, Else, ed. Alfred Wegeners letzte Grönlandfahrt: Die Erlebnisse der Deutschen Grönland-Expedition 1930/31 geschildert von seinen Reisegefährten und nach Tagebüchern des Forschers. Condensed edition. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus Verlag, 1943.

Wegener, Else. Alfred Wegener—Tagebücher, Briefe, Erinnerungen. Wiesbaden: F. A. Brockhaus, 1960.

Wegener, Kurt. Wissenschaftliche Ergebnisse der Deutschen Grönland-Expedition Alfred Wegeners in den Jahren 1929 und 1930/31. 7 vols. Leipzig: F. A. Brockhaus Verlag, 1933–40.

Wutzke, Ulrich. Durch die weiße Wüste: Leben und Leistungen des Grönlandforschers und Entdeckers der Kontinentaldrift Alfred Wegener. Gotha: Perthes, 1997.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter