Milestones of the Anthropocene

Our faces are illuminated by the screen of a smartphone while we fly over entire continents in an airplane in the space of a few hours. High in the air, we snap a photo that we can upload to the Internet in the space of a few seconds: an image of the world beneath us with its large, intensively cultivated fields, giant industrial parks, and container ships 400 meters in length. Ever faster, ever farther, this world keeps turning in a whirlwind of technology and progress, humans and machines.

How did the world come to be the way it is today? What are the defining characteristics of the Anthropocene?

There is no question that the industrialization of the nineteenth century paved the way for the beginning of the Anthropocene. The steam engine was and is the emblem of this era. It was the technological catalyst and driving force behind the economic and technological achievements of the nineteenth century and it set in motion the Industrial Revolution. Steam engines powered machines in the mining, textile, and steel industry. They mechanized and accelerated tasks that previously had to be completed by hand and made energy available anywhere, regardless of location. New forms of transportation—railways and steamships—altered our experience of space and time. In the second half of the nineteenth century, the railroad became one of the leading economic sectors in Germany and its nearly insatiable appetite for coal and steel gave further impetus to industrialization.

Industrialization and mechanization brought new inventions in their wake: Cars and airplanes replaced the railroad, even though they produce substantially more pollution. Today, the steam engine has been replaced by gas, water, wind, and shaft turbines, as well as internal combustion engines. The invention of the diesel motor in 1893 triggered new innovations in shipbuilding. The diesel engine was superior to steam engines in many ways. It could be started immediately without having to be warmed up, it required only a fraction of the space and a third of the operating crew, and it could travel over much longer distances. What it did require, however, was oil as fuel—enormous quantities of it. As merchant shipping expanded it literally fuelled the world economy.

The constant demand for more petroleum was by no means only positive, however. It is a much fought-over resource, costing the lives of humans in wars and causing environmental disasters. In spite of strict safety standards, tanker accidents release many millions of liters of oil into the seas.

Like shipping, agriculture also underwent profound changes as a result of mechanization. Motorized machines, in particular gasoline-powered tractors such as this “Bulldog,” first manufactured in 1921 in Germany, were the beginning of a revolution in speed and efficiency for agriculture.

Artificial fertilizers, too, are just as important as when they were first used. Thanks to them, it is possible to feed a world population that is now approaching 7 billion. But the increase in productivity has negative consequences for the environment: The loss of biological diversity due to monocultures, overfertilization of the soil and eutrophication of the water, and the ethics of factory farming and green genetic engineering. To counteract these developments, people are turning to organic farming and projects such as the “Slow Food” movement.

Every day, there are more people who want to eat. And many of them want a car to drive as well. By the mid-twentieth century there will be an estimated 10 billion cars in the world—all with combustion engines that require large amounts of gasoline and emit immense quantities of polluted gases. The “Eiserne Jungfrau” (Iron Maiden) gasoline pump developed by Shell in 1926 was installed in easily accessible locations on the roadside and designed to withstand a direct impact. It facilitated the sale of gasoline in larger quantities. Previously, gasoline could only be bought at drugstores in small quantities. Infrastructure and technological developments made the automobile what it is today: a symbol of freedom and individuality. Cars, but especially airplanes, contribute substantially to climate change. Therefore it is important to find more economical ways to travel in the Anthropocene.

Although energy-efficient fluorescent lights are beginning to replace traditional light bulbs, many other appliances of our time require immense amounts of electricity. More “power guzzlers” are being sold all the time: in 2012 alone some 350 million personal computers were sold. And disposal of these appliances is a substantial environmental problem. Most of these appliances are used in the Global North. But they are broken down into their components and recycled as e-scrap primarily in the Global South, usually with a high price for humans and their environment.

Today, scarcely anyone under the age of 25 can imagine everyday life in a world without modern technology: cell phones, computers, GPS devices. Other, more mundane appliances such as refrigerators and hair dryers have become standard components of Western households and it is difficult to imagine doing without them. All are the result of important developments and inventions.

Satellite technology is a child of the Cold War, born from the competition between the United States and the Soviet Union to conquer outer space. Refrigerators arrived in Germany only in the 1950s, bringing a taste of the “American way of life” into German households. With the release of the first Macintosh in 1984—the cult product of our information society—Apple made available the first personal computer for home use.

But even these splendid inventions that make our lives so much easier are also a source of problems. It was not until the end of the 1980s that refrigerators with chlorofluorocarbons were banned because of their harmful effect on the climate. Today, debris from old satellites orbits the Earth, while humans and the environment become ill from unrecyclable e-waste. The story of the technological achievements of the Anthropocene is also a story of the problems that they bring with them.

Technology is inextricably part of a culturally determined socio-technical system that interacts with nature at all levels. In the Anthropocene our task is to find a new system in which technological progress is more environmentally friendly and sparing of resources.

The Anthropocene comic project

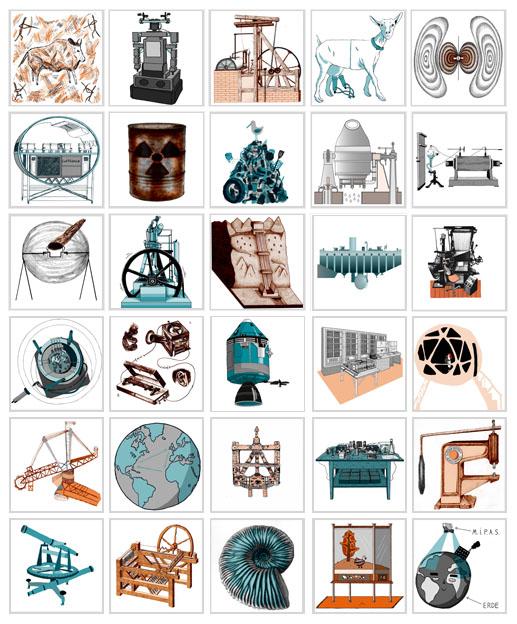

What do the Altamira cave, the spinning jenny, the scanning tunneling microscope, the telephone, and the Apollo mission have in common? One, these items and events are on display at the Deutsches Museum, and two, they represent important milestones that have paved the way to a new geological “age of humans.”

Unfortunately, many of the objects representing historical Anthropocene milestones are on permanent display at the Deutsches Museum and cannot be removed. With this in mind, Henning Wagenbreth, a professor of illustration in visual communication at the University of the Arts (UdK), Berlin, and his students bring us closer to these revolutionary innovations by illustrating them in 30 eight-panel comic strips.

This project, completed with the editorial work of Alexandra Hamann, the academic supervision of Reinhold Leinfelder, and professional guidance of Helmuth Trischler, presents in a creative way the increasingly significant geological footprints of humans on the planet. The comics strips were on display from 5 December 2014 until 31 January 2016 alongside the actual objects exhibited at the Deutsches Museum, in cooperation with the Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society, in the special exhibition “Welcome to the Anthropocene: The Earth in Our Hands”.

They have also been published in German on the website of the Deutsches Museum and as a book accompanying the Anthropocene exhibition. To read the comics in English, please browse through the Art & Graphics collection in the Multimedia Library of the Environment & Society Portal. The comics have been translated by Oliver Liebig and edited by Iris Trautmann and Marielle Dado.