Democratic Green

Who Owns the Olympiapark?

Layered Stories in the Olympiapark

Can I Be Yours?

One Tree, Many Interests

A Story of Peaceful Appropriation

Munich’s Olympiapark has existed since 1972. Landscape architect Günther Grzimek planned it as a people’s park. According to the ideal of a new democratic Germany, the premise was: openness instead of intolerance. Walking on the grass is explicitly permitted!

What sounded revolutionary at the time is commonplace today. So what does “democratic green” mean in the twenty-first century? How open is the park to visitors, really? Would a Russian hermit still be allowed to settle in the Olympiapark? Father Timofej’s house still stands today—a memorial. Will the linden trees also be allowed to remain? The fate of the once proud Munich avenue tree is currently being fiercely debated.

There is a lot of history buried in the Olympiapark. What future do we wish for it? Can we find the balance between a recreational area and an event park?

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of views of the exhibition, where visitors were encouraged to walk on the grass. Photos 1, 2, and 4 by Florin Prună. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Photos 3 and 5 by Christian Eckstein. These works are used by permission of the copyright holder. View the images on the following pages.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

Views of the exhibition, where visitors were encouraged to walk on the grass. Photos 1, 2, and 4 by Florin Prună. These works are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Photos 3 and 5 by Christian Eckstein. These works are used by permission of the copyright holder.

Layered Stories in the Olympiapark

Until 1938, an airport was located on the Oberwiesenfeld, which was used by the National Socialist elite. After the end of the war in 1945, a hill of debris was constructed from the rubble of the bombed city—today’s Olympic hill. In contrast to the Oberwiesenfeld of the past, the Olympiapark was intended to be open to the city and the world. Without rigid restrictions and provisions, social participation was possible for all.

The design emulated the Bavarian landscape: willows around the lake like the ones lining the Isar river, mountain pines on the hillsides as in the Alps, linden trees—the typical Munich avenue tree—along the pathways. Landscape architects praise the park as a symbol of freedom and openness. A section of the grounds is already listed as a historic monument. In the future, it could become a UNESCO World Heritage site.

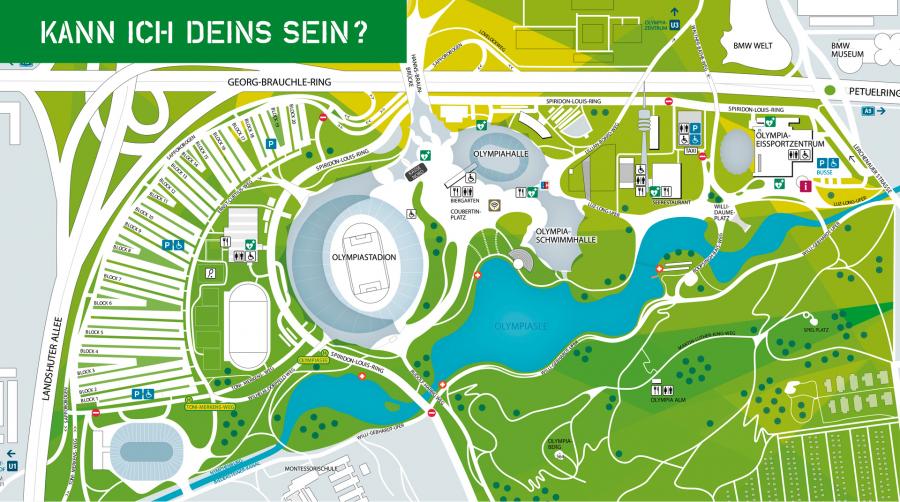

Can I Be Yours?

You can stroll, jog, dance, and eat; you can go to Tollwood or the Impark summer festival, see live bands or the EHC Red Bull hockey team, or visit the Theatron sea stage. You can celebrate different cultures, like the Japanese cherry blossom festival. The Olympiapark fulfills many roles: it is an event venue, a recreational area for people, and a habitat for animals and plants.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images from the Olympiapark. View the images on the following pages.

Numerous advertising posters vouch for the variety of events in the park.

All photos are by Marlen Elders. These works are used by permission of the copyright holder.

Bathing is not allowed in the Olympic lake, which is only 1.3 meters deep. Ducks, geese, and swans do swim here though.

The lake flows through to the Nymphenburg-Biederstein canal and is supplied with rainwater from the huge stadium roofs.

Under new management, it is hoped that the park will remain profitable, but also improve environmentally. In 2016, it switched to 100 percent green electricity. There is a constant need to weigh these aspects against one another and to renegotiate the different interests concerning how the park is used. In the future, it will also be necessary to ask: Whom and what purpose should the park serve? How do we perceive the park?

What remains open to discussion is how the park can be rejuvenated and, at the same time, preserved. Should it become a UNESCO World Heritage site? Is it (still) a place of democratic appropriation? Whose ideas and needs will it satisfy?

What does your park look like? What does our park look like?

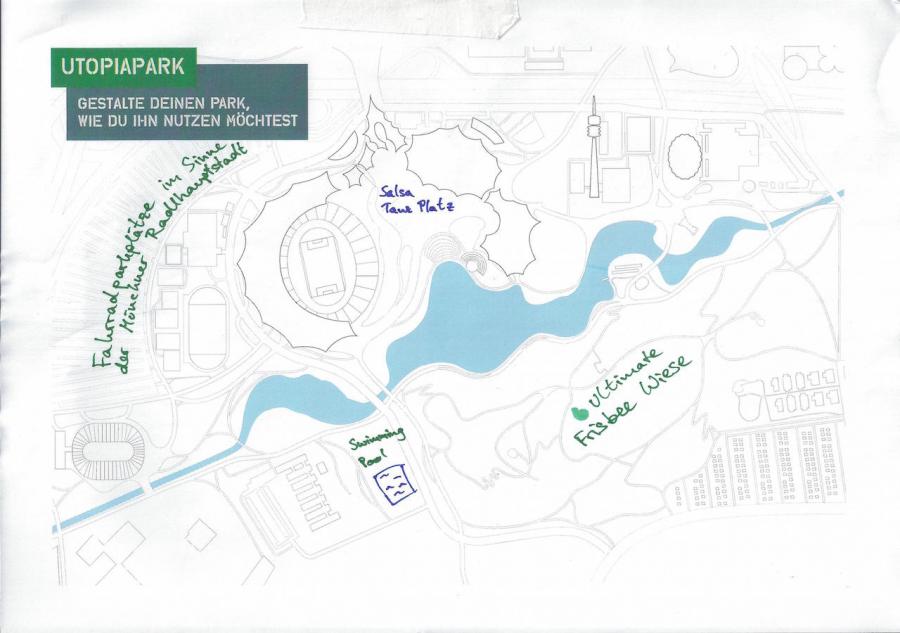

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of maps of the Olympiapark. View the images on the following pages.

The map was designed by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Map designed by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Map designed by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Exhibition visitors were asked to design the Olympiapark. Here are four anonymous answers to the question of what the park should look like. The map was designed by Katharina Kuhlmann and Alfred Küng.

One Tree, Many Interests

Honey from the non-commercial beekeeper association of the Ost-West-Friedenskirche (East-West Peace Church). Two beekeepers look after Timofej’s old beehives. The bees’ main source of food are the blossoming linden trees in the park. Photo: Florin Prună

Honey from the non-commercial beekeeper association of the Ost-West-Friedenskirche (East-West Peace Church). Two beekeepers look after Timofej’s old beehives. The bees’ main source of food are the blossoming linden trees in the park. Photo: Florin Prună

Florin Prună (2017)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

The linden is a classic Munich avenue tree. That’s why it was selected for the Olympiapark and lines its main paths. Recently, however, it has gone out of style—aphids living in the trees produce a sweet and sticky honeydew. Come June, the dripping liquid is a nuisance to many, sticking to car windows and walkways. Beekeepers, on the other hand, appreciate the honeydew and pollen-rich flowers of the linden. These food sources make the linden one of the most crucial trees for bees and other insects in the city.

Unlike for bees and beekeepers, for city planners the importance of city trees is based on the specific ecosystem services they perform: they should grow evenly and their roots should not reach too deeply. They must also be resistant to dog urine and road salt and, in light of climate change, also to heat and periods of drought.

These things do not make it easy for the linden to remain a typical city tree in Munich. It is likely that in the future more suitable “climate trees” will be planted: the Japanese Pagoda tree, English oak, or Ginkgo.

The original exhibition includes an interactive gallery of linden tree images. View the images on the following pages.

A Story of Peaceful Appropriation

Hidden behind bushes and trees, amid a gravel fallow, Father Timofej’s chapel is located. The Russian hermit Timofej Prokhorov settled here in 1952 together with his companion Natascha. Out of debris from World War II that was gathered on the Oberwiesenfeld, they built a church for Saint Mary and established a place of peace.

They planted fruit trees, shrubs, flowers, and vegetables to provide for themselves and to offer a home to bees, birds, and other living creatures. Thus a small section of today’s Olympiapark was transformed into an oasis of calm, which has always welcomed visitors from all over the world.

The home-grown fruit and vegetables served as the basis of their livelihoods. They exchanged harvest surpluses for other foodstuffs or sold them to visitors. It was rumored that Timofej had the best apples in town. The former Lord Mayor, Christian Ude, likes to tell that, as a boy, he used to sneak into the garden to steal the delicious apples.

It is a story of peaceful, subversive appropriation—Timofej had neither a building permit nor a purchase agreement. In a wondrous way, Timofej defied official attempts to evict him and even fought the construction plans for the 1972 Olympic Games.

Even today, thirteen years after the death of the Russian hermit, fruit trees blossom here, bees buzz, and visitors stroll along the winding paths. Managed by a small association that cares for the church and garden, the place still exudes the unconventional spirit of the wise father.

This short film gives a tour of where Father Timofej lived and built his church. From the fruit trees and the bees that collected their nectar and pollen to the icons that decorate the church’s interior, the video offers a glimpse of Father Timofej’s flourishing legacy. Marlen Elders, 2017, 3 min 56 s.

The original exhibition features a short film of a tour of where Father Timofej lived and built his church. From the fruit trees and the bees that collected their nectar and pollen to the icons that decorate the church’s interior, the video offers a glimpse of Father Timofej’s flourishing legacy. Marlen Elders, 2017, 3 min 56 s. View the film online here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4GmEtyuNnRU.

Curators: Marlen Elders, Laura Kuen, and Maya Schmitt

How to Cite: Elders, Marlen, Laura Kuen, and Maya Schmitt. “Democratic Green.” In “Ecopolis München,” edited by L. Sasha Gora. Environment & Society Portal, Virtual Exhibitions 2017, no. 2. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. http://www.environmentandsociety.org/node/8051.