Introduction: The Promise of Free Land

This Virtual Exhibition features one of the millions of small stories of homesteading in the US West. Lily Bell Murray Stearns Schuld Lampp overcame early tragedy in Illinois that left her an orphan, moving through Saskatchewan and Iowa before she arrived in Montana to claim 320 acres (129.5 hectares) of “free land” under the terms of the 1909 Enlarged Homestead Act. Stearns’s saga captures both the risks and the opportunities of the Great Plains during the early twentieth century. Stearns was one of 14,891 homesteaders who successfully proved up in Montana in 1917, the year of greatest homestead success during the long homestead era (1863–1986), but her experiences evoke how the erratic fortunes of farm life reflected the abundant economic, political, and personal whims of the era.

This exhibit is derived from research conducted for a book project, Little Piece of Earth: The Hidden History of the Homestead Era, that uses microhistorical methods to excavate the multiple histories of areas that achieved high rates of homesteading success, reclaiming the histories of the land and peoples on which these land claims were sited. Lily Stearns’s story, placed within the largest successful homestead rush in history, foregrounds the personal saga of one woman who struggled to find security and a sense of pace within the sweeping demographic and geopolitical changes of her day.

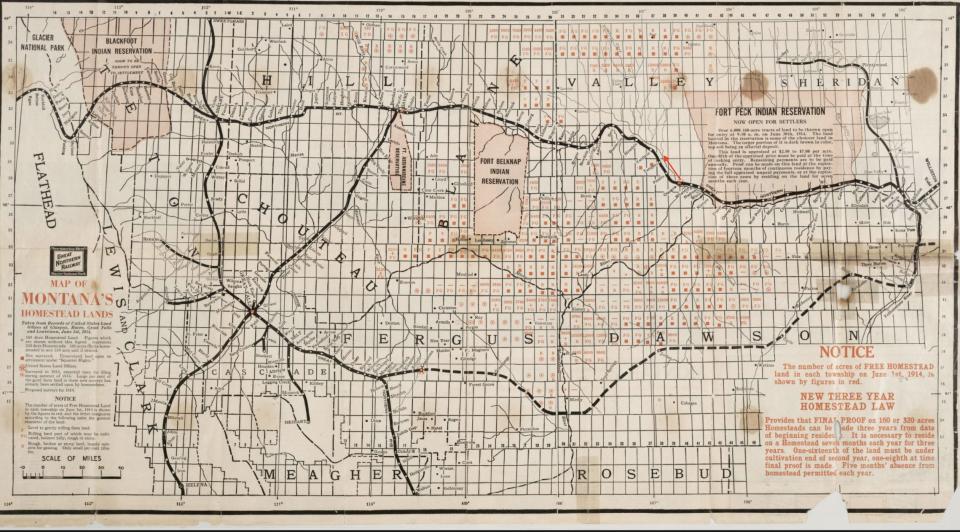

Map of the Enlarged Homestead region of Montana, 1910, with the Fort Peck Indian Reservation featured prominently in the upper left corner, and Glasgow just west, along the north bank of the Milk River.

Map of the Enlarged Homestead region of Montana, 1910, with the Fort Peck Indian Reservation featured prominently in the upper left corner, and Glasgow just west, along the north bank of the Milk River.

Courtesy University of Montana Special Collections.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Arriving in Montana

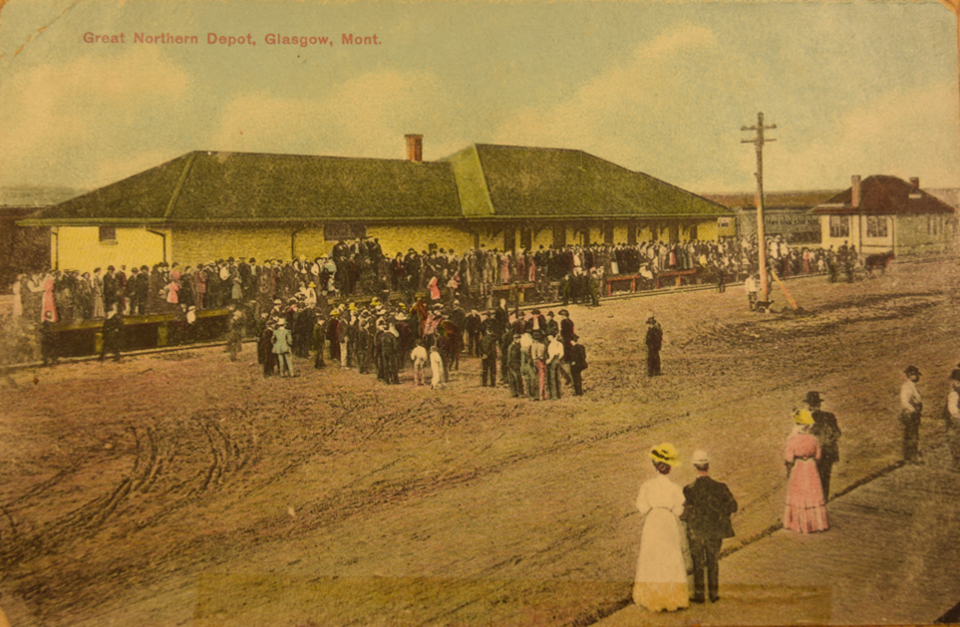

In October 1912 Lily Bell Stearns stepped off the westbound Great Northern train at the squat depot in Glasgow, Montana, poised to gamble on the promise of a booming country. She had set her sights on homesteading in Montana decades into the homestead era, hoping to find stability and land of her own from a national land policy that demanded little capital yet proffered security for aspiring farmers.

Glasgow Depot, where Lily Stearns disembarked from the Great Northern Line. Unknown photographer, no date.

Glasgow Depot, where Lily Stearns disembarked from the Great Northern Line. Unknown photographer, no date.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy Valley County Historical Society, Glasgow, Montana.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Beginning in 1862 a series of Homestead Acts conveyed territory from the vast public domain to individual settlers in exchange for their labor and improvements. This land transfer represented the culmination of a long process of Indigenous dispossession, and a gamble for farmers unaccustomed to the challenging climate of the Northern Plains, but it was masked by the rhetoric of US policymakers who emphasized that the homestead laws worked to expand access to land more democratically than ever before.

The railroads were instrumental in advertising the expansive homestead lands still available on the Northern Plains, as shown by the red markers on the townships with land available for enlarged homestead claims. Great Northern Railway Map of Montana, 1914.

The railroads were instrumental in advertising the expansive homestead lands still available on the Northern Plains, as shown by the red markers on the townships with land available for enlarged homestead claims. Great Northern Railway Map of Montana, 1914.

Unknown cartographer, 1914.

Courtesy University of Montana Special Collections and the Montana Memory Project.

Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Advertisement from the back of the Great Northern Railway Map of Montana.

Advertisement from the back of the Great Northern Railway Map of Montana.

Unknown photographer and artist, 1914.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

New arrivals thronged the US Land Office in Glasgow in the years following the passage of the 1909 Enlarged Homestead Act, which promised to unlock the potential of this region for dry-land farming by doubling the maximum acreage of homesteads (to 320 acres/129.5 hectares). The ensuing surge into Montana represents the largest successful movement of homesteaders in US history, and it briefly transformed the northeastern quarter of the state from a vast expanse of rolling grasslands into a patchwork of small farms.

This tumultuous last rush onto American homesteads was encouraged by members of Congress, local boosters, and railroad promoters, who joined with one voice to urge land-seekers from around the world to claim their share before it was all snatched up. In this semiarid region the Glasgow Commercial Club celebrated how “the fertility of the soil is not leached out by too much water as is the case in other districts,” a dubious benefit about which any clear-headed farmer would have thought twice. As had been the case during earlier homestead rushes, a boomer mentality dominated in eastern Montana, where the ancestral knowledge of the challenges of thriving in this region had been cordoned off among the Dakota and Assiniboine people who had been removed to the Fort Peck Indian Reservation under the 1886/1887 Agreements of Shortgrass Hills. These peoples would have stressed that the key to survival was movement across the occasionally punishing prairie, a strategy that was the antithesis of the homesteading ideal.

Opportunity beckoned, and aspiring settlers arrived imbued with the confidence that evolving technologies and new methods would guarantee crop yields under even the toughest conditions. Homesteading offered the possibility of security on the rich soils and rolling terrain of the northern Great Plains, but the speed of the homestead movement elided the difficulties presented by precipitation, soils, and the short growing season in this challenging region. The following chapters trace the arc of Lily Stearns’s experiences on the shortgrass prairie of northeastern Montana, as she scratched a farm within a community and a landscape that challenged her hopes of securing a stable future for her family.

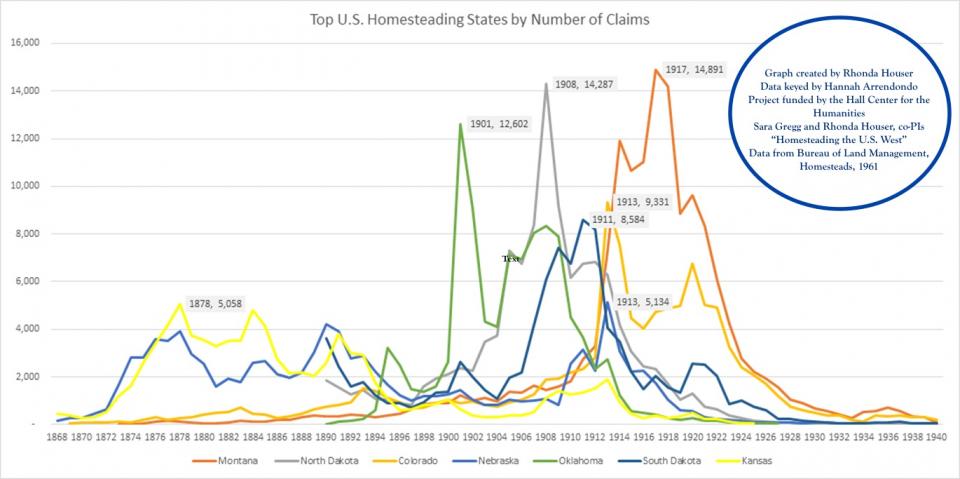

Contrary to popular beliefs, the peak of successful homesteading took place after 1900, and this graph demonstrates the impact of successful claims by year—with peaks in Oklahoma, 1901, North Dakota, 1908, and Montana, the national height, in 1917—the year that Lily Stearns finalized her claim. Graph by Rhonda Houser.

Contrary to popular beliefs, the peak of successful homesteading took place after 1900, and this graph demonstrates the impact of successful claims by year—with peaks in Oklahoma, 1901, North Dakota, 1908, and Montana, the national height, in 1917—the year that Lily Stearns finalized her claim. Graph by Rhonda Houser.

Graph by Rhonda Houser.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter