The American Forestry Association announces its “Hall of Fame for Trees” in 1920.

The American Forestry Association announces its “Hall of Fame for Trees” in 1920.

“‘Hall of Fame’ for Trees,” American Forestry 26 (January 1920): 2.

Click here to view HathiTrust source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The idea of the “champion tree” has a surprising pedigree. It began in 1914, when the American Genetic Association—a eugenics organization—sponsored a contest to find the largest trees in the nation, excluding conifers and non-natives. The AGA was interested in native plants that achieved “greatest development” in human-modified landscapes. “Superior” strains of “thrifty” species might then be propagated. Photographic results of the contest were published in the Journal of Heredity (formerly American Breeder’s Magazine) the following year. An American sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) in a cornfield near Worthington, Indiana, won the prize for its 42-inch (107-centimeter) circumference. The authors of the report called for the preservation of “magnificent members of the vegetable kingdom”—though they stopped short of making direct comparisons to human breeding.

Meanwhile, in the realm of conifers, the Save-the-Redwoods League worked to preserve the supertrees of America. The council of the League, founded in 1918, was a who’s who of American conservationists and eugenicists. In the interwar years, the League focused its attention and resources on preserving California’s “best” grove, home of the “world’s tallest tree.”

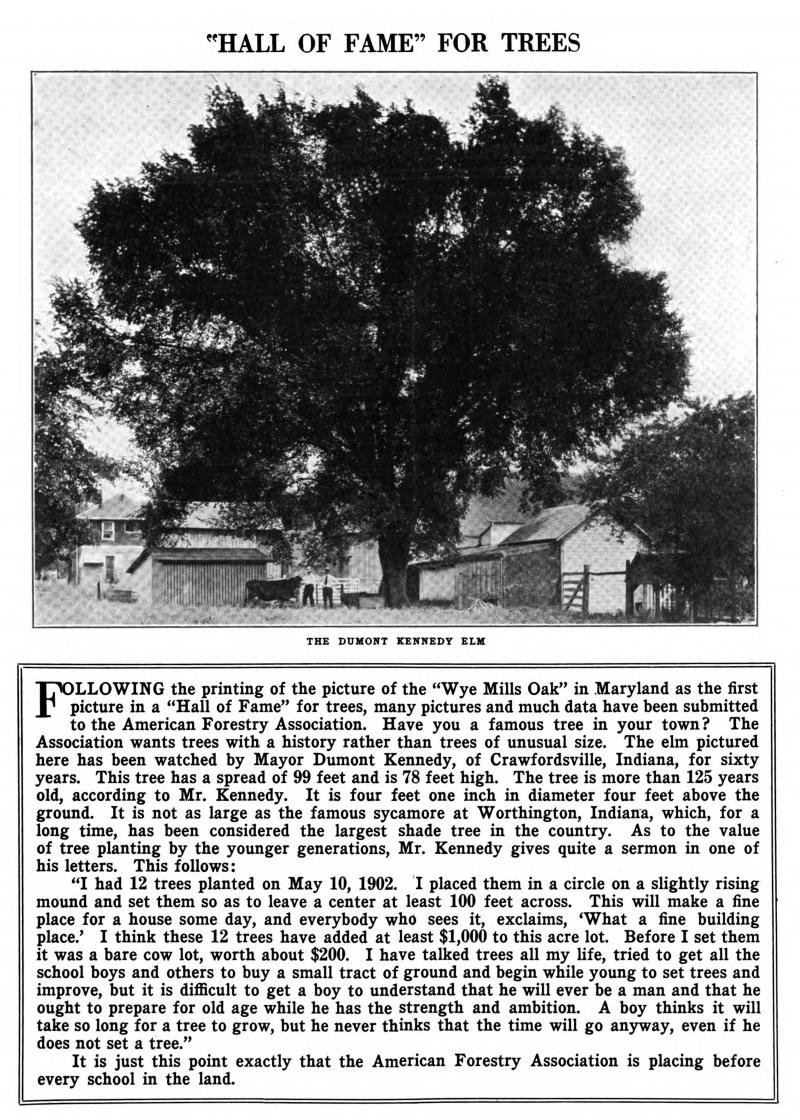

In parallel, in 1919, the American Forestry Association initiated its “Hall of Fame for Trees,” with the goals of identifying the nation’s largest shade trees and bringing national attention to locally famous trees. The AFA encouraged schoolchildren to nominate specimens from their hometowns. Of the dozens of nominees profiled in the magazine American Forests in 1920–1922, many conformed to the established genre of nationalistic “historic trees”—plants that had “witnessed” patriotic history. For example, the Daughters of the American Revolution nominated Washington trees, Lafayette trees, and so on. But, significantly, some of the poster-print hall-of-famers were simply big trees with no historical associations. Although the AFA indicated that it preferred “trees with a history rather than trees of unusual size,” it contradicted itself with its first inductee—the Wye Oak of Maryland, a tree famous only for its size.

The Wye Oak in 1936.

The Wye Oak in 1936.

Photograph by E. H. Pickering, 1936.

Courtesy of Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, HABS MD,21-WYM,2–2. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Hall of Fame for Trees morphed into the Social Register of Big Trees, now called the National Big Tree Program. Since 1940, the AFA (now called American Forests) has maintained a species-by-species database of “champion” specimens based on an idiosyncratic calculation. Trunk circumference in inches + Height in feet + Average crown spread in feet, divided by four = Total points. This scoring system advantages single-bole, wide-canopy trees—i.e., photogenic plants in open settings. Each year, new winners are announced, as tree-hunters, mainly men, dethrone previous titleholders. Champion trees sometimes die, reopening the field.

The point system is a legacy of Fred Besley, an early graduate (1904) of Yale’s forestry school. Besley found employment as Maryland’s original state forester, a position he occupied for nearly four decades. In 1925, he began sponsoring a statewide “Big Tree contest,” a competitive form of what is now called crowdsourcing. After some local controversy—multiple cities and counties claimed oaken supremacy—Besley determined that the big tree in Wye Mills, Talbot County, was the biggest white oak not only in Maryland, but the nation. He oversaw a nursery program that distributed seedlings, grown from Wye Oak acorns, for ceremonial plantings. In response to Besley’s advocacy, the State of Maryland in 1941 purchased the land around the national champion, established a state park, and adopted the species (Quercus alba) as the official state tree. When Besley retired the next year, his colleagues presented him with a pair of engraved bookends constructed from Wye Oak wood.

To this day, the quantification and listing of national champion trees remains popular in the United States. There is something distinctively American—and masculinist—about the practice: bigger means better, biggest wins first prize, and the winner gets a photo shoot. British and European dendrophiles, and Canadian old-growth activists, have recently borrowed the practice of “champion tree” registries, but only Americans conduct a full-fledged competition. This tradition benefits from intranational rivalries between the 50 states.

The remains of the Wye Oak in 2009.

The remains of the Wye Oak in 2009.

Photograph by Jeff Weese, July 2009.

Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

A muted echo of the eugenics movement can still be heard in champion-tree talk. In recent years, the US-based Archangel Ancient Tree Archive has made worldwide news with its project of cloning record holders, including the tallest redwoods. (“Champion Trees are the Answer” is the organization’s motto.) By propagating the “best of the best,” the archive hopes to promote reforestation and carbon sequestration. The charity made clones of the Wye Oak before it toppled in a storm in 2002, and planted them at Mount Vernon, George Washington’s plantation. The logic of the group’s well-meaning program derives more from American culture than botanical science. Champion trees are certainly amazing, but they are not, in fact, genetically superior, simply lucky: the beneficiaries of optimal conditions.

As for the Wye Oak, a pedigreed sapling grows near the stump of its progenitor, which is now protected by a wooden pavilion. The bulk of the fallen landmark was fashioned into a desk for the governor of Maryland.

How to cite

Farmer, Jared. “American Champion Trees and the Wye Oak of Maryland.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2019), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8502.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Jared Farmer

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Besley, F. W. Big Tree Champions of Maryland: A Record of the Largest Trees of the Principal Species. Baltimore: Maryland State Forestry Association, 1955.

- Buckley, Geoffrey L., and J. Morgan Grove. “Sowing the Seeds of Forest Conservation: Fred Besley and the Maryland Story, 1906–1923.” Maryland Historical Magazine 96, no. 3 (September 2001): 303–27.

- Farmer, Jared. Trees in Paradise: A California History. New York: W. W. Norton, 2013.

- Jorgenson, Lisa. Grand Trees of America: Our State and Champion Trees. Niwot, CO: Roberts Rinehart Publishers, 1992.

- Preston, Dickson J. Wye Oak: The History of a Great Tree. Cambridge, MD: Tidewater Publishers, 1972.

- Robbins, Jim. The Man Who Planted Trees: Lost Groves, Champion Trees, and an Urgent Plan to Save our Planet. New York: Spiegel & Grau, 2012.

- Stern, Alexandra Minna. Eugenic Nation: Faults and Frontiers of Better Breeding in Modern America. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2015.