Komodo National Park from seaside

Komodo National Park from seaside

2012 Tyler Ray

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

The most famous inhabitant of Komodo National Park is certainly the Varanus komodoensis—the “Komodo dragon”—a 90-kilogram carnivorous lizard with a fatally poisonous bite. Several thousand of these extraordinary beasts exist on the small, eastern Indonesian islands of Komodo and Rinca, and as a result of their presence the area has been under some form of protection since the Dutch colonial era.

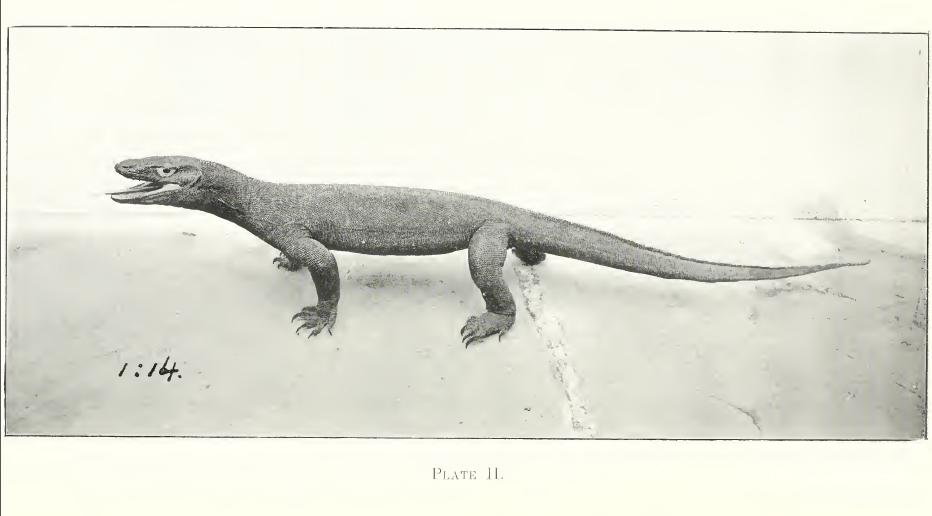

“Komodo Dragon” (1912), he first published image of the full Varanus Komodoensis

“Komodo Dragon” (1912), he first published image of the full Varanus Komodoensis

In the 1912 volume of the Bulletin du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg the Dutch zoologist Peter A. Ouwens was the first to publish a description and photos of a previously unknown and very large varanus species that he proposed to call: Varanus Komodensis.

Ouwens, Peter A. “On a Large Varanus Species from the Island of Komodo.” Bulletin du Jardin Botanique de Buitenzorg, ser. 2, no. 6 (1911–12): 3.

Click here to view Internet Archive source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

“Komodo Dragon” (2008)

“Komodo Dragon” (2008)

2008 Jason Coleman

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

But the national park (established in 1980) also protects the marvelous marine environment around the islands, which contains a dazzling array of reef-building coral and sponges, and an extraordinary assortment of fish species, as well as sea turtles, mantas, whales, dolphins, and sharks. Humans have inhabited the islands for centuries, but like much of the population of the poverty-stricken regions of eastern Indonesia, the villagers live at a subsistence level, eking out their existence largely though fishing and collecting sea products.

Village on Komodo island

Village on Komodo island

2011 Robert Scales

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

While the islands are remote—Komodo was once a penal colony—in the 1990s, the park became a popular destination for independent backpackers and tour groups, mostly arriving from Bali. Annual visitation numbers surged to over 30,000 in 1996, generating substantial revenue for this underdeveloped region. Conflicts soon emerged between conservationists and the local population over access to the park’s terrestrial and marine resources, a battle that was aggravated by the breakdown of the Indonesian economy in 1997, the toppling of the Suharto regime in 1998, and the complete collapse of the tourism industry in the wake of the 2002 terrorist bombing in Bali. The implementation of legislation in 1999, which devolved control over national parks from the central government to the regencies, complicated Komodo’s already tangled administration. During this tumultuous period, the Indonesian government called upon the Nature Conservancy to help protect the park, and in conjunction with the Indonesian Directorate General for Nature Conservation and Protection, the Conservancy produced a comprehensive plan for the long-term management of Komodo.

However, the Conservancy’s program was undermined by the regency government of West Manggarai, which refused to surrender the administration of the park, and a local population that resented the Conservancy’s stricter enforcement of conservation policies. After the departure of the Conservancy in 2010, the park fell under the supervision of a regency government notorious for mismanagement practices, for example the granting of mining permits in the park’s vicinity.

Local fisherboat at Labuan Bajo harbor on Komodo

Local fisherboat at Labuan Bajo harbor on Komodo

2006 Nutch Bicer

Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.0 Generic License.

By 2008, tourism to the park had rebounded and continues to grow, but the economic benefits from this expanding industry have been concentrated in the gateway town of Labuan Bajo, the capital of the regency of West Manggarai. A small fishing village in the 1980s, as a result of the national park Labuan Bajo has become a regional hub, with an airport and a developed infrastructure to supply the modern conveniences demanded by international tourists.

The national park is a principal generator of wealth for the regency and has a decisive influence on the politics of the region. For the broader Indonesian public, Komodo is a remote location—less than ten percent of the tourists to the park are domestic Indonesians. Nevertheless, the national park has become a world-renowned attraction, and its future management and the distribution of its economic benefits will involve contests between a range of interests, including regional leaders, the Indonesian government, international conservation organizations, tourism entrepreneurs, local fisherman, and the residents of the park. The continued conflict or eventual reconciliation between these various stakeholders will provide a valuable case study for assessing the local, long-term political and economic consequences of expanding tourism at national parks in other developing regions of Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

How to cite

Rodriguez, Steven. “Bitten by Success: Conflicts Over Tourism Revenue and Natural Resources at Komodo National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2014), no. 3. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5701.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2014 Steven Rodriguez

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Borchers, Henning. Jurassic Wilderness: Ecotourism as a Conservation Strategy in Komodo National Park, Indonesia. Stuttgart: Ibiden, 2004.

- Erb, Maribeth. “The Dissonance of Conservation: Environmentalities and the Environmentalisms of the Poor in Eastern Indonesia.” The Raffles Bulletin of Zoology 25 (2012): 11–23.

- Hitchcock, Michael. “Dragon Tourism in Komodo, Eastern Indonesia.” In Tourism in South-East Asia, edited by Michael Hitchcock, Victor T. King, and Michael Parnwell, 303–16. London: Routledge, 1993.

- Pannell, Sandra. Reconciling Nature and Culture in a Global Context? Lessons from the World Heritage List. Cairns: Cooperative Research Centre for Tropical Rainforest Ecology and Management / Rainforest CRC, 2006.

- Walpole, Matthew J., and Harold J. Goodwin. “Local Economic Impacts of Dragon Tourism in Indonesia.” Annals of Tourism Research 27 (2000): 559–76.