During the 1960s, for the first time since the conclusion of the Second World War and the subsequent civil war of 1946–49, Greece experienced signs of rapid growth. Although somewhat belated, this was when the country entered what John McNeill and Peter Engelke have described as the “Great Acceleration” of the Anthropocene, in which humankind in the mid-twentieth century became the main force transforming earth.

By the 1960s, the battle of “man against nature” in Greece thus took a new turn. The imperative of intensified and mechanized agricultural production—even for smallholders who constituted the large majority of Greek farmers—dictated the extermination of certain wildlife. Additionally, the glorification of private property as opposed to the traditional commons of the past, the introduction of imported affordable semi-automatic firearms, and the promotion of hunting as an activity that could bring “modern” men in the capital city of Athens in touch with their “manly nature” all worked to popularize a type of hunter that was presented as a role model to the hunting community: the Hero-Hunter, a standard of virtue and selflessness.

It is unclear whether the Hero-Hunter role model originated in traditional societies that utilized hunting as a means for sustenance or whether it first emerged with the establishment of hunting as a recreational activity. Older hunting publications from the turn of the twentieth century do not pay any special attention to the social duties that hunters should undertake. In the 1960s, however, this ideal was disseminated to thousands of Greek hunters through the pages of the most prominent Athens-based hunting magazine at the time, Kynegetika Nea (Hunting News). And, as a relatively egalitarian activity accessible to both rural and urban hunters, the Hero-Hunter ideal addressed a broad audience.

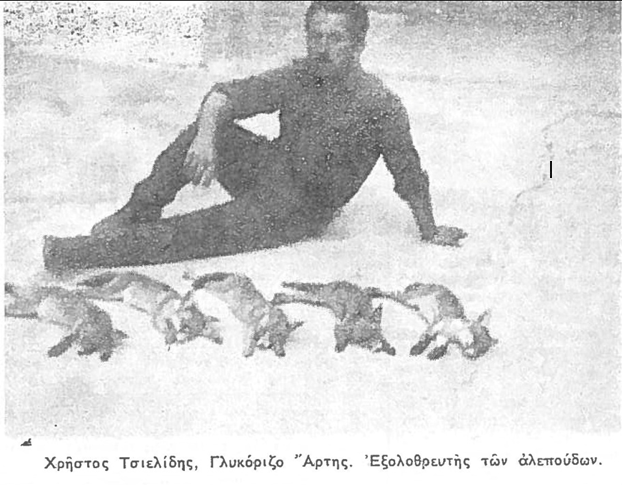

Photograph from Kynegetika Nea (Hunting News). The caption reads: “Christos Tsielidis, Glykorizo Artas. Exterminator of Foxes.”

Photograph from Kynegetika Nea (Hunting News). The caption reads: “Christos Tsielidis, Glykorizo Artas. Exterminator of Foxes.”

© Dimitris Basourakos

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The most highlighted characteristic of the Hero-Hunter was his dedication to the community and the alleviation of economic hardship through wildlife extermination. Foxes, feral house cats, wild boars, squirrels, ravens, badgers, and rabbits were all seen as dangerous to the productivity of rural communities that therefore had to strive to keep non-productive or harmful fauna at bay. Admiration for those who took a stand against such “vermin” was common, with photographs of exterminators posing near their dead prey often appearing in the pages of magazines, accompanied by triumphant captions.

These esteemed individuals were portrayed as selfless utilitarians struggling for the greater good of the community, farmers, and peasants, as seen in a report of an organized cull in 1969, where the hunt was celebrated with a feast:

Chasing the corvids of Patras

… More than fifty hunters marched across the Lappa-Metochi area [northwest Peloponnese] around five o’clock in the afternoon and decimated agriculture-threatening birds during roosting.

Elated by the shootout, which had been very efficient due to the easiness of the targets, they later proceeded to [the nearby village of] Niforeika and celebrated with grilled meat and good wine.

According to our information, these valuable campaigns will continue, so not only will the number of magpies decrease, but our Nimrods will also keep fit until August.

Good Hero-Hunters also follow an unwritten Code of Honor, beyond what was dictated by law, recognizing that a true hunter should feel compassion for their prey and know when to let it escape, acknowledging any disadvantage it may have. Though the application of this code could be vague in practical situations—just as its Western European counterpart of “Fair Chase” is—many contributors to the magazine were quite adamant about it:

Photograph from Kynegetika Nea (Hunting News). The caption reads: “In the regional forestry of Edessa, 30 foxes were killed and 7 fox cubs were taken alive. In the photograph, we see the exterminator of vermin Georgios Kosmiadis, resident of the village Daphne.”

Photograph from Kynegetika Nea (Hunting News). The caption reads: “In the regional forestry of Edessa, 30 foxes were killed and 7 fox cubs were taken alive. In the photograph, we see the exterminator of vermin Georgios Kosmiadis, resident of the village Daphne.”

© Dimitris Basourakos

Used by permissionThe copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Law gave hunters a firearm and rules. Nature gave the prey an inherent defense. The war is between them. Every war, though, has its written and unwritten rules and if someone is to take victory, he must fight with honesty, abiding by these inviolable rules, in order to be called victorious.

Victory achieved through dishonest thoughts and dishonest acts shows nothing more than DISHONOR and UNMANLINESS!

While other aspects of the Hero-Hunter ideal did not change much over time, this Code of Honor would come to lose importance. The ideal re-emerged from time to time when wildlife threatened the interests of farmers or shepherds, with the one difference that technological advancements were gradually embraced, especially in the form of more reliable cars and more efficient firearms. While several editors of Kyngetika Nea—along with Kynegesia kai Kynofilia (Hunting and Cynophilia), a hunting press newcomer after 1975—initially resented the encroachment of technology on their sport, insisting on traditional values, the access to new unspoiled hunting grounds with the popularization of 4x4 cars and the increased precision of shotguns led to increased hunting successes.

In an era characterized by what has been described as the sixth mass extinction, hunting technology increasingly tilts the balance in favor of hunters. In this context, we may question to what extent the hunting community can continue to uphold the ideal of the Hero-Hunter and ignore the fact that he is just another agent of the Anthropocene clad in a traditional gown, barely held together by misguided romanticism.

How to cite

Vlachos, George L. “The Emergence of the Hero-Hunter in the Greek Anthropocene.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2024), no. 12. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi:10.5282/rcc/9854.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2024 George Vlachos

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.