A significant weakness of commonplace records of the first four centuries of Brazil’s history is that they do not capture the wide range of interactions between humans and nonhuman animals, nor recognize them as an essential element in the formation of Brazilian society. Despite this limited formal recognition, selected narratives regarding the period that spans from the dawn of the sixteenth through the end of the nineteenth century provide valuable insights and raise new questions regarding such interactions.

Brazil’s territory around the end of the nineteenth century.

Brazil’s territory around the end of the nineteenth century.

Map by João Coelho, 1891.

© 2000 Cartography Associates. David Rumsey Map Collection, list no. 5467.001. Click here to view Cartography Associates source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic License.

An analysis of fragments from approximately 130 writings, such as diaries, letters, and other primary and secondary sources, reveals that nonhuman animals were intensively involved in events and were described and used in a myriad of often contradictory ways. Animals appear as things, as food, occasionally as beings capable of expressing feelings and human-like behavior, as sources of spiritual power for native groups, as medicine available for all those living in the tropical environment, as cargo and transportation, and as elements in play, sport, and domestic leisure. They also served as symbols and metaphors for Brazilian society itself, alluding to a wild New World to be conquered, and were seen as assets of the Portuguese Crown as well as threats to both human survival and settlers’ property. For priests, the actions of certain animals or even their mere presence could be taken as an expression of the devil’s force or the power of God. Paying attention to these meanings and functions can shed light on the still obscure role of nonhuman animals during this chapter of Brazilian history.

Photograph of Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802–1858)

Photograph of Johann Moritz Rugendas (1802–1858)

Calotype photograph by Franz Hanfstaengl, n.d. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Since history is essentially built from the arguments of those who bear language, historical fact is constituted as a narrative that is communicated and thus kept alive in collective memory. Yet iconography provides insight that can deepen our understanding of those who were given no voice and thus remain on the periphery of the historical record. The artist’s eye, which is usually attracted to the strange and the unexpected, has the potential to reveal channels of recognition for those things that words cannot explain or that seem unusual in daily life.

Following the opening of Brazilian ports to international trade in 1808, many European artists traveled to Brazil, taking up the challenging mission of drawing and conveying the New World to Europe. Johann Moritz Rugendas, a German artist who graduated from the Munich Academy, arrived for his first stay in Brazil in 1821. He remained in the country for two years, visiting a number of different regions. In his drawings, later converted into lithographs, Portuguese South America was depicted from a refined and detailed standpoint.

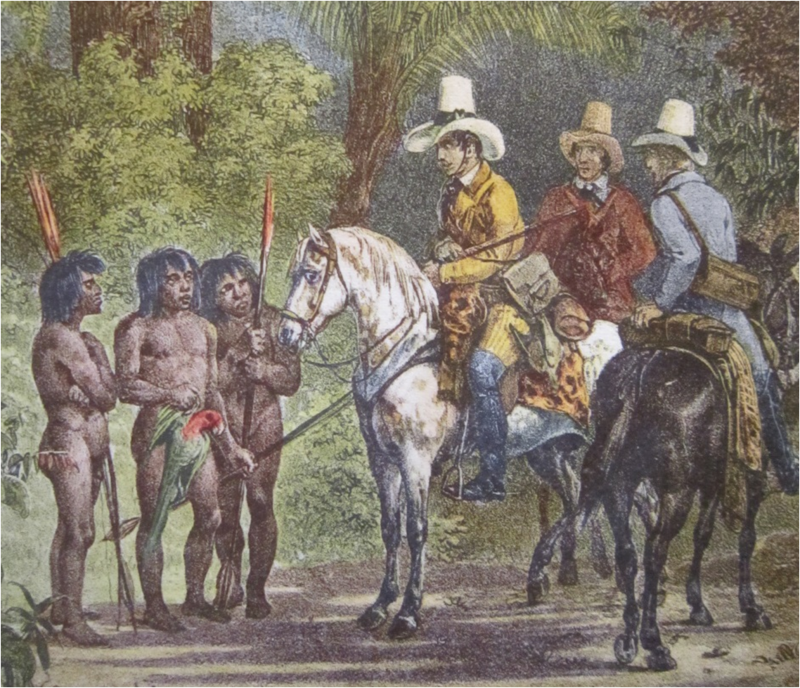

There is a peculiar proximity between a dead parrot, the first symbol that represented the new territory, and horses, which were highly associated with the values and the power of the Portuguese Crown. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Rencontre d’Indiens avec des voyageurs europeens. c. 1821–1825.

There is a peculiar proximity between a dead parrot, the first symbol that represented the new territory, and horses, which were highly associated with the values and the power of the Portuguese Crown. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Rencontre d’Indiens avec des voyageurs europeens. c. 1821–1825.

Colorized lithograph by Johann Moritz Rugendas. From Rugendas, Johann Moritz. Malerische Reise in Brasilien. Facsimile of the first edition. Stuttgart: Daco-Verlag Bläse, 1986.

Courtesy of Senado Federal do Brasil. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Rugendas was also able to perceive the place of animals in a dense network of interactions, identifying some of the most representative bonds that had already come into being in the early sixteenth century. In his book Voyage pittoresque dans le Brésil, published in 1835, some of his pictures suggested a synthesis of these hybrid associations in the everyday scenario of the ongoing meetings formed and performed by native people, European explorers, enslaved Africans, and animals such as parrots, jaguars, horses, and cattle, to mention just a few.

An intricate scene of domination and brutality involving settlers, horses, mules, and slaves. Usually, human and nonhuman workers were used for the same work of transporting cargo or people. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Porto do Estrela. c. 1821–1825.

An intricate scene of domination and brutality involving settlers, horses, mules, and slaves. Usually, human and nonhuman workers were used for the same work of transporting cargo or people. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Porto do Estrela. c. 1821–1825.

Colorized lithograph by Johann Moritz Rugendas. From Rugendas, Johann Moritz. Malerische Reise in Brasilien. Facsimile of the first edition. Stuttgart: Daco-Verlag Bläse, 1986.

Courtesy of Senado Federal do Brasil. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Both native fauna and domesticated species from Europe were represented in impressive detail, suggesting that they could be recognized as more than goods, and perhaps as actors. In his writings, Rugendas revealed his concern for the conditions of animals in diverse circumstances, demonstrating an accurate perception of the adaptation of European domestic species to the tropical environment, as well as the subtle nuances of the behavior of innumerable wild species. As he also noted, the main characters of Brazilian society were its quadrupeds and this recognition was genuinely demonstrated in his collection of drawings. Cattle moving across extensive territory, riders sitting astride their horses, “troops of mules” crossing rivers, military cavalry occupying the streets of colonial cities, slaves and oxen working together in sugar mills undoubtedly associated with the very meaning of colonization.

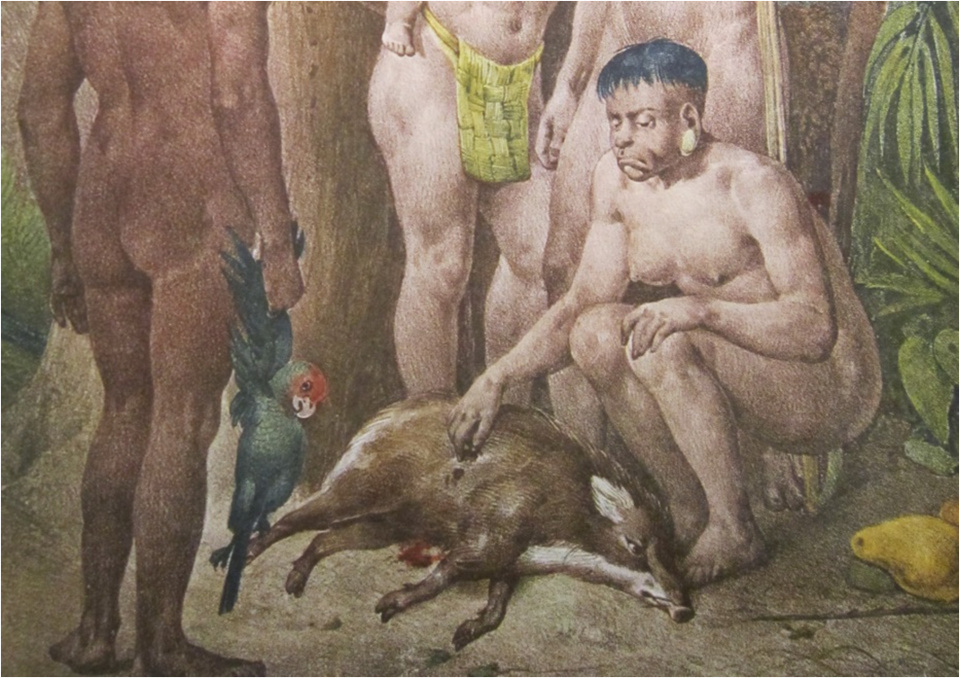

All kinds of wild species—except poisonous ones—were considered to be food by the native peoples and this habit was steadily adopted by the settlers as well. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Famille indienne, c. 1821–1825.

All kinds of wild species—except poisonous ones—were considered to be food by the native peoples and this habit was steadily adopted by the settlers as well. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Famille indienne, c. 1821–1825.

Colorized lithograph by Johann Moritz Rugendas. From Rugendas, Johann Moritz. Malerische Reise in Brasilien. Facsimile of the first edition. Stuttgart: Daco-Verlag Bläse, 1986.

Courtesy of Senado Federal do Brasil. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Cattle and African slaves working together to power sugar mills, the economic core of the colonial system. Other European domestic animals, such as goats, lived within these farms. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Moulin à sucre, c. 1821–1825.

Cattle and African slaves working together to power sugar mills, the economic core of the colonial system. Other European domestic animals, such as goats, lived within these farms. Detail from Johann Moritz Rugendas, Moulin à sucre, c. 1821–1825.

Colorized lithograph by Johann Moritz Rugendas. From Rugendas, Johann Moritz. Malerische Reise in Brasilien. Facsimile of the first edition. Stuttgart: Daco-Verlag Bläse, 1986.

Courtesy of Senado Federal do Brasil. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Hunting activities improved initial cooperation between the first European explorers and the native people, the latter described by Rugendas as highly skilled hunters. He depicted them cooking a monkey and killing a jaguar, both types of animals bearing strong symbolic reference to native cosmology. In Meeting of the Indians and European Explorers, a remarkable contrast in hunting approaches is suggested. The indigenous people, naked and armed with arrows, were able to move quickly and silently toward their prey, while Europeans with their horses and noisy shotguns were almost sure to scare the wild game away. It is worth noting that the opening of the ports gave a further boost to hunting, meant to supply the several European scientific missions that were spread out across Brazilian territory.

In light of the paucity of existing records on this subject within Brazilian environmental history, research on the probable convergence of iconographic records and discursive narratives may provide valuable material to the field of human-animal studies. The variegated testimony of human-animal partnership in Rugendas’s artwork may be best appreciated through an integrated perspective that examines the relevant social, economic, and environmental factors that are able to afford us a greater understanding of these relationships.

How to cite

Camphora, Ana Lucia. “J. M. Rugendas’ Contribution to an Iconography of the Animal Condition in Nineteenth-Century Brazilian Society.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2018), no. 24. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8360.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 Ana Lucia Camphora

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Anderson, Virginia DeJohn. Creatures of Empire: How Domestic Animals Transformed Early America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004.

- Camphora, Ana Lucia. Animais e sociedade no Brasil dos séculos XVI a XIX [Animals and Society in Brazil from the Sixteenth to the Nineteenth Century]. Rio de Janeiro: Ana Lucia Camphora, 2017.

- Few, Martha, and Zeb Tortorici, eds. Centering Animals in Latin American History. Durham. NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

- Kury, Lorelai, ed. Representações da fauna no Brasil—séculos XVI–XX. Rio de Janeiro: Andrea Jakobsson Estúdios, 2015.

- Mariante, Arthur da Silva, and Neusa Cavalcante. Animais domésticos da história do Brasil. Brasília: EMBRAPA, 2000.

- Rugendas, Johan Moritz. Malerische Reise in Brasilien. Stuttgart: Daco-Verlag Bläse, 1986. (Available for download here.)

- Spix, Johann Baptist von, and Karl Frederick Philipp von Martius. Travels in Brazil in the Years 1817–1820. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, Brown, and Green, 1824. (Available for download here.)