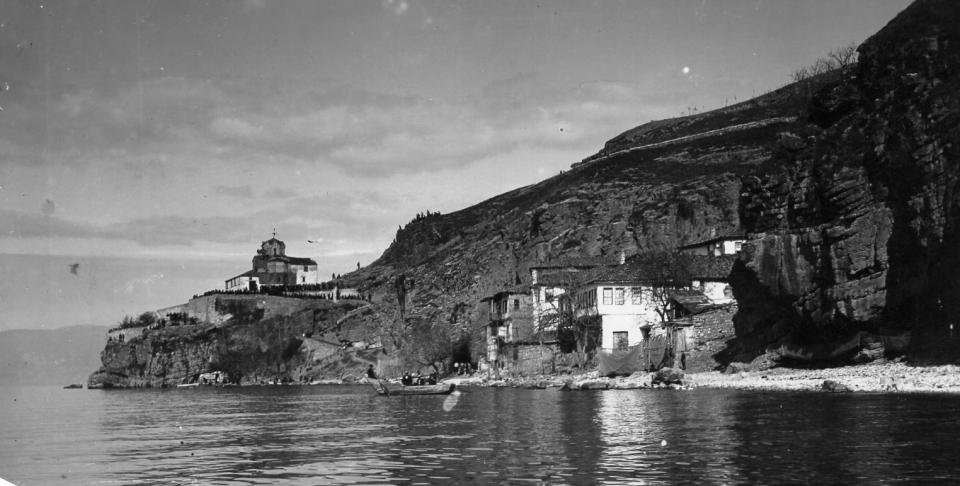

The old town of Ohrid before the building of the new tourist promenade.

The old town of Ohrid before the building of the new tourist promenade.

Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of the State Archives of the Republic of Macedonia (DARM), Skopje Department.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

Lake Ohrid, often dubbed the “Pearl of the Balkans,” is shared by present-day North Macedonia and Albania. Along with its lakeside town of the same name, Lake Ohrid has served as an important natural and cultural site and as a destination for tens of thousands of tourists annually. How can such a visually stunning yet extremely fragile environment be simultaneously developed to accommodate masses of tourists and protected to preserve its unique features? North Macedonia’s communist Yugoslav predecessors (1945–91) provided the first extensive framework for striking a balance between protection and exploitation in Ohrid in the 1970s and 1980s, and set the foundations for many current policies and approaches. Despite Yugoslavia’s emphasis on rapid development as a modernizing socialist country, by the 1970s the leadership set up a system of “rational planning,” promising to sustainably develop Ohrid as part of the overall socio-economic development of Yugoslavia. By the collapse of the Yugoslav Federation in 1991, the country had been able to transform Ohrid into a modern tourist destination while protecting much of its unique heritage.

Before renovation and tourism, St. Jovan Kaneo in the 1930s.

Before renovation and tourism, St. Jovan Kaneo in the 1930s.

Courtesya of the State Archives of the Republic of Macedonia (DARM).

Accessed via Wikimedia on 12 June 2019. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

As one of the oldest and deepest lakes in Europe, Ohrid is home to many endemic species of flora and fauna not found anywhere else in the world. The old town of Ohrid that straddles the northern shores of the lake is also home to a unique fusion of Roman, Byzantine, Ottoman, and Slavic heritage. But after Ohrid came under the People’s Republic (later Socialist Republic) of Macedonia as part of the Yugoslav Federation in 1945, the new communist leadership increasingly looked to tourism as a viable new economic path for underdeveloped regions like Ohrid. By the 1960s, the country was actively seeking to attract foreign—especially Western—visitors who promised to bring hard currency into the country.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Yugoslav-published guidebooks lured visitors by presenting Ohrid as being simultaneously frozen in time and rapidly modernizing, conforming to the standards of the adventure- and comfort-seeking tourist. This somewhat contradictory picture of Ohrid continued to be presented by the Yugoslav tourist industry well into the 1970s as tourism reached new heights, growing rapidly and steadily—the total number of visitors rose from just under 35,000 in 1960 to 136,000 in 1980, with over half a million overnight stays. Already by 1975, tourism was considered to be the main engine behind the Ohrid region’s increasing urbanization and infrastructural development.

Despite this relative economic success, the explosion of tourism on Ohrid’s shores coincided with a realization of the need for sustainable development within the socialist modernization project, especially after the Stockholm Declaration (1972) initiated the United Nations Environment Programme. The Yugoslav leadership took the declaration very seriously, and it directly inspired a new federal environmental protection law in 1974, which considered it to be the responsibility of all working people, citizens, organizations, and communities in Yugoslavia to protect and “advance” the country’s natural resources. These attitudes directly affected the development of Ohrid as a tourist destination, as its protection was meant to benefit the local population and all of Yugoslavia.

Since economic development was part of a unified goal, tourism had to share Ohrid with agriculture and industry, the latter of which was especially prone to colliding with tourism. While one 1974 development plan for Ohrid considered tourism to be the most “suitable” for the region because of its natural “values,” it also called for further development of the chemical, textile, and metallurgical industries. With possible conflicts between industrial development, tourism, and preservation in mind, in 1972 the leadership initiated a spatial plan for Ohrid and nearby lake Prespa. The plan was meant to provide a physical framework that would simultaneously prevent conflicts, ensure economic growth, and preserve the region’s natural and cultural treasures.

The 1972 spatial plan for Ohrid was an international affair that included representatives of different Yugoslav urban institutes and experts selected by the OECD. While the experts emphasized tourism’s central importance in Ohrid’s development, they also acknowledged its destructive potential and included some specific measures for environmental protection—especially for wastewater management, protecting rare endemic species, and maintaining built heritage.

Environmental protection in Ohrid was then given a huge boost in 1980 when the Yugoslav part of the lake and town was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site, making it one of the first combined natural and cultural sites to be given protected status. Tourism experts in Yugoslavia viewed the inclusion of Ohrid on the list as a chance for tourism and environmental protection to coexist, with the Faculty of Tourism in the Socialist Republic of Macedonia viewing it as confirmation of both Ohrid’s global environmental importance and its potential to develop into a world-class tourist destination. Though many of the environmental pressures from tourism continued to challenge the health and aesthetic quality of Ohrid, the system in place was able to maintain a degree of equilibrium between accommodating tourists and promising sustainable development through “rational planning,” even if the former often took precedence over the latter.

In the spring of 2019—almost three decades after the collapse of Yugoslavia—UNESCO threatened to place Ohrid on its list of Endangered Sites, mainly due to overdevelopment and illegal construction. Since independence, North Macedonia has struggled to manage its protection efforts. Ohrid’s protection in the 1970s and 1980s was done with great international and inter-republic attention and collaboration, and if it is to continue to enjoy special protection as tourism continues to rise, further international engagement is vital.

How to cite

Djordjevski, Josef M. “Managing Tourism and Environmental Protection in Lake Ohrid in the 1970s and 1980s.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Summer 2019), no. 25. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8799.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Josef M. Djordjevski

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Jancar, Barbara. “Environmental Protection: ‘The Tragedy of the Republics.’” In Yugoslavia in the 1980s, edited by Sabrina Ramet, 224–46. Boulder & London: Westview Press, 1985.

- Kostrowicki, Jerzy and Wieslawa Tyszkiewicz, eds. Transformation of Rural Areas: Proceedings of the 1st Polish-Yugoslav Geographical Seminar, Ohrid, 24–29 May, 1975. Warsaw: Polish Academy of Sciences, Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization, 1978.

- Popovski, Jovan. Ohrid. Beograd & Skopje: Nova Makedonija, 1967.

- Sobranie na Opštinata Ohrid. Osnovi na Stopanskiot, Opštestveniot Razvoj i Budžetska Potrošuvačka na Opštinata Ohrid za 1974 Godina. Ohrid: Kosta Abraševiќ, 1974.

- Regionalen Prostoren Plan na Ohridsko-Prespanskiot Region. Ohrid: Direkcija za Prostorno Planiranje, 1972.

- Univerzitet vo Bitola i Fakultet za Turizam i Ugostitelstvo, Ohrid. Zbornik na Trudovi. Ohrid: Kosta Abraševiќ, 1981.