The sea at the Hanko Peninsula

The sea at the Hanko Peninsula

Photograph by Heikki Siltala. Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

On 30 October 1970, the local newspaper Västra Nyland revealed that the Finnish state-owned oil company Neste had tried, using a front, to buy hundreds of hectares of land on the Hanko Peninsula in southern Finland. The area was located next to Tvärminne Zoological Station, established in 1902 as a field station of the University of Helsinki. In November 1970, Neste admitted that the company was interested in the Hanko Peninsula, but maintained that no decision had yet been made as to the location of the company’s (and Finland’s) planned third oil refinery. In reality, Neste had already decided to build a refinery on the peninsula’s east coast. Furthermore, Neste and its well-connected and powerful director Uolevi Raade, used to getting their way even after highly publicized oil spills in 1969, were confident that the plans would be given the green light politically, regardless of any environmental concerns.

The blue waters of Lappohja Beach on the east coast of the Hanko Peninsula, a few kilometers north of the proposed site of Neste’s oil refinery

The blue waters of Lappohja Beach on the east coast of the Hanko Peninsula, a few kilometers north of the proposed site of Neste’s oil refinery

Photograph by Alexander Ulyanov. Click here to view Flickr source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License.

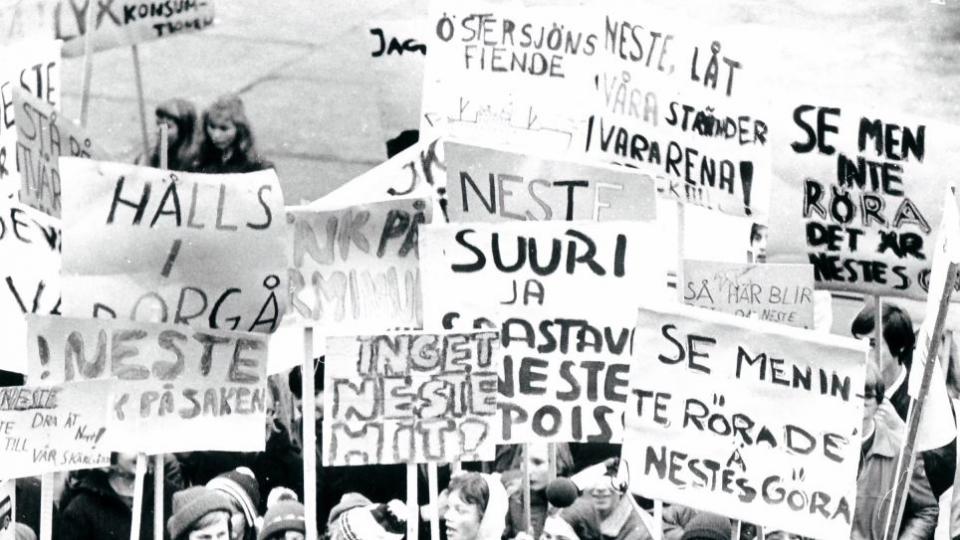

Even though Neste tried to conceal its intentions, they were obvious enough to members of the local community and the researchers at Tvärminne Zoological Station. Emboldened by a newly awakened environmental consciousness, raised in part by the 1970 European Conservation Year, they began organizing against Neste’s plans at the end of 1970. Protest rallies with schoolchildren were staged in the nearby towns of Ekenäs and Hanko on 16 November. In Ekenäs almost 400 children chanted “Look but don’t touch, that’s what Neste must do” and admonished the company to “Stay in Borgå”—the location of one of their other refineries. The same year, similar environmental conflicts had erupted in other Nordic countries—most notably in Eikesdal in Norway, where activists engaged in civil disobedience to protest against the building of a dam—and the activist reactions that followed inspired the local actors organizing against Neste’s plans.

The schoolchildren’s protest in the town of Ekenäs, now part of the town of Raseborg, 16 November 1970. Some of the signs of the protesters read: “No Neste here!”; “The enemy of the Baltic Sea”; “The great and polluting Neste away”; “Neste, think about it”; “Neste, let our beaches stay clean.”

The schoolchildren’s protest in the town of Ekenäs, now part of the town of Raseborg, 16 November 1970. Some of the signs of the protesters read: “No Neste here!”; “The enemy of the Baltic Sea”; “The great and polluting Neste away”; “Neste, think about it”; “Neste, let our beaches stay clean.”

© Västra Nylands arkiv/The archive of Västra Nyland. Unknown photographer.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The so-called Neste War, Finland’s first comprehensive public environmental conflict, began in earnest at the beginning of 1971 when Neste finally announced that the company had decided that it would build its third refinery on the Hanko Peninsula. When Neste made its objectives public, large parts of the local and scientific communities mobilized against the plans in a way never before seen in Finland. On 26 January 1971, the Action Group for the Archipelago of Nyland, an environmental activist group made up mainly of male members of the bourgeois elite from the predominantly Swedish-speaking town of Ekenäs (just north of the proposed site), was formed. The action group joined forces with the researchers at Tvärminne Zoological Station as well as the newspapers Västra Nyland and Nya Pressen, and initiated a campaign against Neste’s refinery project. The centerpiece of the campaign was the collection of signatures for a protest petition, which was accompanied by a wave of letters to the editor, as well as opinion pieces written by concerned scientists. The action group and the University of Helsinki also presented the environmental and scientific case against Neste’s plans at public meetings that they arranged. In just a few months, the petition had collected 73,621 signatures, and on 1 April it was delivered to the Finnish prime minister Ahti Karjalainen.

The editors of the newspapers Västra Nyland and Nya Pressen (the two men on the left) handing over 13,528 petition signatures to two representatives of the Action Group for the Archipelago of Nyland (the two men on the right).

The editors of the newspapers Västra Nyland and Nya Pressen (the two men on the left) handing over 13,528 petition signatures to two representatives of the Action Group for the Archipelago of Nyland (the two men on the right).

© Västra Nylands arkiv/The archive of Västra Nyland. Unknown photographer.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

The combination of expert and public polemic, as well as the scale of the protest, took Neste by surprise. The company was unable to prevent the project from receiving media attention and the subsequent politicization of the case saw the government respond by setting up a committee to oversee it. As a state-run company, however, Neste had strong support from the Finnish labor movement. Social Democrats and Communists saw government-led industrialization as a progressive way to create jobs, and many in the labor movement, especially among the older generations, regarded environmentalism as both radical and utopian. At the same time, environmentalism was growing within the Finnish Left, primarily within the Social Democratic party.

On 7 July 1971, the committee recommended in favor of Neste, but by that time most of Finland’s authorities on environmental issues had taken a stand against the company’s project. More importantly, the non-left parties began opposing Neste’s plans, leaving only the Social Democrats and Communists in support of the company, although by this time only half-heartedly. As a new Social Democrat minority government formed in February 1972, the oil company believed that it would finally be able to procure the political decision it craved. However, on 21 July 1972, only six days after the new prime minister Rafael Paasio visited Tvärminne Zoological Station to acquaint himself with the proposed site of the refinery, the government declared that no refinery was to be built on the Hanko Peninsula. The Finnish oil giant had been defeated. The budding Finnish environmental movement had won its first major victory through a coalition of perhaps unlikely allies: concerned upstanding citizens and previously politically aloof marine researchers had come together as environmental activists and contributed to the keeping the black oil of Neste out of the blue waters of their respective social and scientific habitats.

Neste’s refinery in Porvoo, 2011. The Neste War could have ended with a with a similar refinery on the west coast of the Hanko Peninsula

Neste’s refinery in Porvoo, 2011. The Neste War could have ended with a with a similar refinery on the west coast of the Hanko Peninsula

Photograph by Jukka Wallenheimo. Click here to view Wikimedia source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License.

How to cite

Wickström, Mats, Hanna Lindberg, and Matias Kaihovirta. “The Neste War 1970–1972: The First Victory of the Budding Finnish Environmental Movement.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2018), no. 8. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8223.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2018 Mats Wickström, Hanna Lindberg, and Matias Kaihovirta

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Armiero, Marco and Lise Sedrez, eds. A History of Environmentalism: Local Struggles, Global Histories. London: Bloomsbury, 2014.

- Jamison, Andrew, Ron Eyerman, and Jacqueline Cramer. The Making of the New Environmental Consciousness: A Comparative Study of the Environmental Movements in Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 1990.

- Kuisma, Markku. Kylmä sota, kuuma öljy: Neste, Suomi ja kaksi Eurooppaa 1948–1979. Helsinki: WSOY, 1997.

- Laakkonen, Simo, and Antti Lehmuskoski. “Musta meri: öljyonnettomuuksien ympäristöhistoriaa Suomessa vuoteen 1969.” Historiallinen Aikakauskirja 103, no. 4 (2005): 381–96.

- Räsänen, Tuomas. “Converging Environmental Knowledge: Re-evaluating the Birth of Modern Environmentalism in Finland.” Environment and History 18, no. 2 (2012): 159–81.

- Räsänen, Tuomas. “Itämeren ympäristökriisi ja uuden merisuhteen synty Suomessa 1960-luvulta 1970-luvun puoliväliin.” PhD diss., Turun yliopisto, 2015.