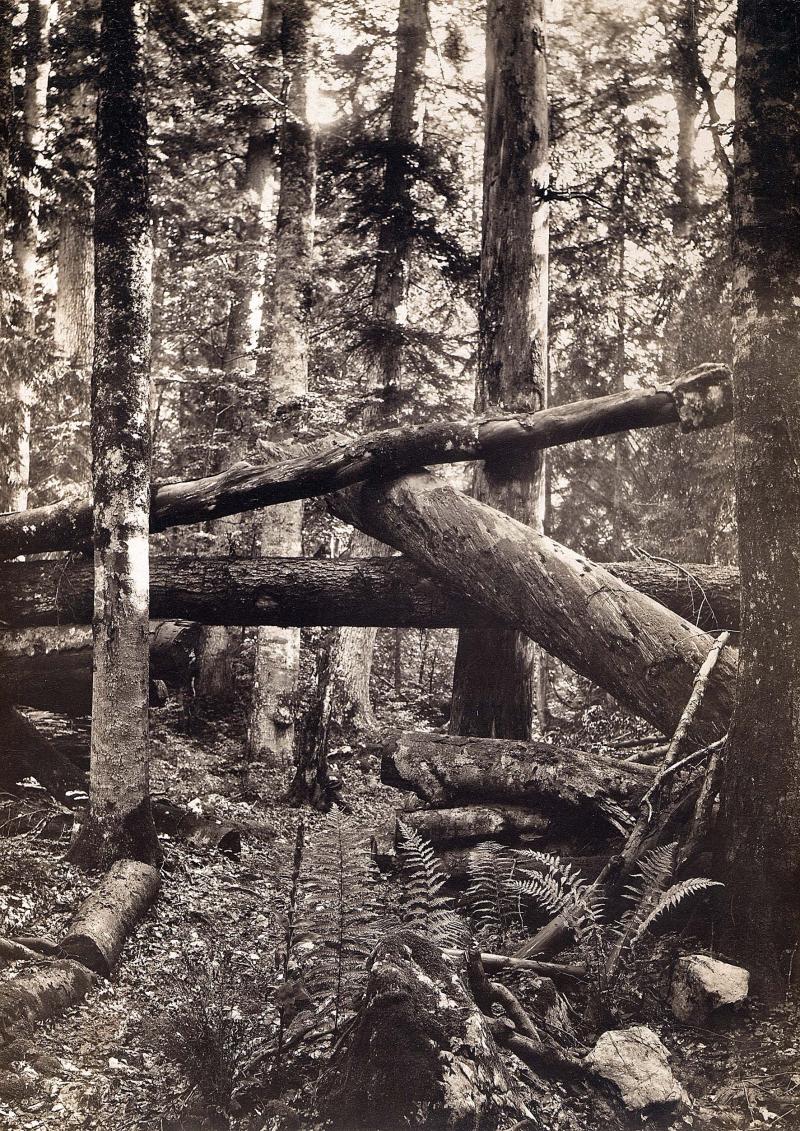

Historical photograph of typical scenery in the Urwald Rothwald taken by Albert Rothschild or his son Alphonse around 1890 (exact date unknown).

Historical photograph of typical scenery in the Urwald Rothwald taken by Albert Rothschild or his son Alphonse around 1890 (exact date unknown).

The photograph was taken by Albert Rothschild or his son Alphonse around 1890 (exact date unknown).

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

When Albert Rothschild came to visit his summer and hunting residence in Holzhüttenboden, the first thing was to saddle his horse and ride to his favorite place named “Goldplatzl” (Golden Place) within his beloved hunting ground in the now called “Urwald Rothwald.” Here and there, even today, the remains of the riding paths that were created for him can still be seen within this primeval forest located in the Northern Limestone Alps, a mere two-hour drive from Austria’s only megacity and capital, Vienna. He had bought the land from an industrial forest company in 1875 and had decided—as the wealthy landlord he was—that the remaining 420 hectares of wilderness had to be left alone and saved from forest use. He was not only a keen hunter but also a nature lover and a pioneer of photography. Without him, the precious piece of wilderness would have been lost. But why did this forest persist untouched through time, while almost all other forests in similar elevation had been exploited for the iron industry in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries?

First of all, it is located in a truly remote place between the modern-day provinces Lower Austria and Styria, a border that goes back centuries. During most of the regencies of the houses of Babenberg and Habsburg (from 975 to 1918), these provinces were two independent duchies. The area surrounding the primeval forest was the only part of the Duchy of Austria that drained towards Styria. Together with the flat terrain in the lower parts of the primeval forest, this was a major obstacle for the transportation of wood using gravity and water.

In the immediate vicinity of the Urwald Rothwald, we find another interesting historical piece in the puzzle of why it remained undisturbed for so long: three different creeks, all of them named “Lassing.” This situation caused legal battles over the correct border between Austria and Styria and between the neighboring monasteries Gaming and Admont, that continued for 337 years. Starting in 1332, the land around the primeval forest belonged to the monastery in Gaming, together with 30,000 hectares of property endowed by the Habsburg Duke Albrecht II. The conflict with Admont concerned hunting and grazing rights, as forestry did not play a role at that time. In 1689 the dispute was settled by an agreement to alternate the right of use annually between the monasteries; i.e., the rent for grazing was shared.

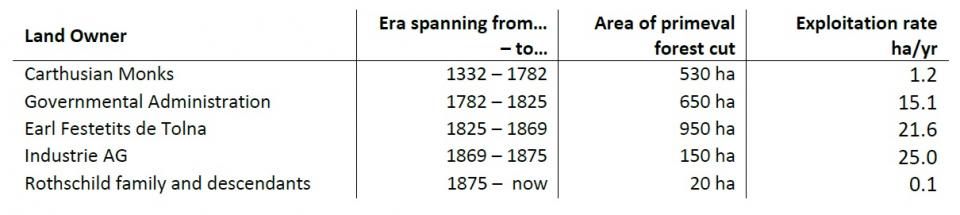

History of land ownership, area of primeval forest cut, and exploitation rate per year during each era. Information from old forest records and maps. Note the different lengths of periods. “ha” stands for hectares.

History of land ownership, area of primeval forest cut, and exploitation rate per year during each era. Information from old forest records and maps. Note the different lengths of periods. “ha” stands for hectares.

Table by Bernhard E. Splechtna and Karl Splechtna.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

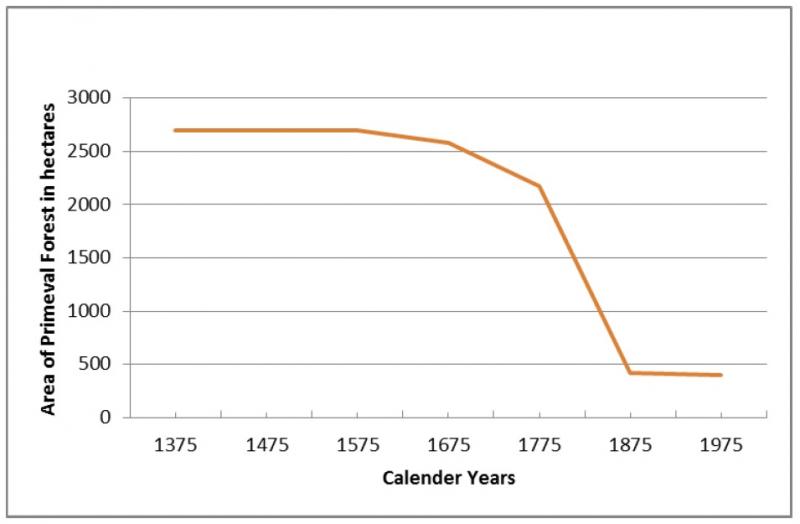

Reconstructed exploitation of the Forest District Rothwald (3,130 hectares in total), showing the loss of 1,650 hectares of primeval forest over ninety years, from 1782 to 1875.

Reconstructed exploitation of the Forest District Rothwald (3,130 hectares in total), showing the loss of 1,650 hectares of primeval forest over ninety years, from 1782 to 1875.

Graphic produced by Bernhard E. Splechtna and Karl Splechtna.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

In 1782, the monastery in Gaming was expropriated by the first enlightened ruler of the Habsburg lands, Josef II. In the following ninety years, 1,650 hectares of primeval forest were removed, until Albert Rothschild put forest use to a halt. Unfavorable circumstances for timber extraction (terrain, political boundaries, and economic disputes over land between monasteries) helped to postpone exploitation long enough, so that this man with passion and foresight could save the most prominent primeval forest of the Alps until modern nature conservation legislation took over. Today, the Urwald Rothwald represents the origin and centerpiece of the Wilderness Area Dürrenstein (IUCN category I) encompassing an area of 3,500 hectares.

Typical scenery beneath the closed canopy. The red ribbon on an old beech (Fagus sylvatica) stems from research activities.

Typical scenery beneath the closed canopy. The red ribbon on an old beech (Fagus sylvatica) stems from research activities.

Photo by Karl Splechtna.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

Medium-sized gap in the primeval forest.

Medium-sized gap in the primeval forest.

Photo by Bernhard Splechtna.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

How to cite

Splechtna, Bernhard E., and Karl Splechtna. “Rothschild’s Wilderness.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2016), no. 4. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/7420.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2016 Bernhard E. Splechtna, and Karl Splechtna.

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Gratzer, G., B. Vesilinovic, and H. P. Lang. “Urwälder in Mitteleuropa—die Reste der Wildnis.“ In Silva fera 1 (2012): 16-29.

- Kral, F., and H. Mayer. “Pollenanalytische Überprüfung des Urwaldcharakters in den Naturwaldreservaten Rothwald und Neuwald (Niederösterreichische Kalkalpen).” Forstwissenschaftliches Centralblatt 87 (1968): 150–175.

- Splechtna, Bernhard E., G. Gratzer, and B. A. Black. “Disturbance History of a European Old-Growth Mixed-Species Forest—A Spatial Dendro-Ecological Analysis.” Journal of Vegetation Science 16 (2005): 511-22.

- Splechtna, Karl. “Wildnisgebiet Dürrenstein—Albert Rothschild Bergwaldreservat: Skizzen einer Nutzungsgeschichte.” In LIFE-Projekt Wildnisgebiet Dürrenstein—Managementplan, edited by Hartmut Gossow, 75-81. St. Pölten: Amt der Niederösterreichischen Landesregierung, Abteilung Naturschutz, 2001.

- Zukrigl, K., G. Eckhart, and J. Nather. Standortkundliche Untersuchungen in Urwaldresten der Niederösterreichischen Kalkalpen. Mitteilungen der Forstlichen Bundes-Versuchsanstalt Mariabrunn no. 62. Vienna: Österreichischer Agrarverlag, 1963.