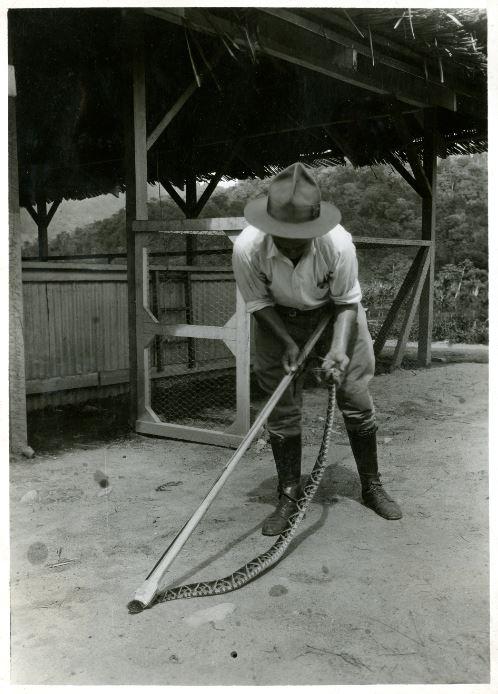

Snake and snake-handler at the Lancetilla research station, 1920s.

Snake and snake-handler at the Lancetilla research station, 1920s.

Unknown photographer, 1920s.

Courtesy of the United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Tela, Honduras. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The 1899 arrival of the Boston-based United Fruit Company in Latin America stands out as a flashpoint in the history of multinational corporate meddling in the economies, politics, and environments across the Caribbean Basin. Primarily in the banana production business, United Fruit lives on today as “Chiquita” with some twenty thousand employees spread across 70 countries. The United Fruit Company (henceforth UFCo) is the quintessential case study in quickly-evolving forms of neocolonial capitalist ventures whose monopolistic ambitions often entwined with the developing hegemonic geopolitical agenda of the United States over the course of the twentieth century. Historians have written extensively on the sordid political-economic machinations of UFCo, yet scholars have only more recently started to entangle these histories with research that centers the human and natural landscapes upon which this enterprise unfurled.

In January 1926, UFCo finished the construction of the main facilities of the Lancetilla Agricultural Experiment Station in Honduras. A five-kilometer tramway connected the station to the Caribbean port town of Tela, which served as a key hub of UFCo administration and infrastructure. The purpose of the station was to conduct research relevant to the large-scale cultivation of tropical fruit, and included research on pests, plant diseases, cover crops, and new fruit varietals. Among the projects that took place at Lancetilla, the Serpentarium stands out. Established in 1926 as an official branch of the Antivenin Institute of America, this snake facility was a collaboration between UFCo and the Pennsylvania-based Mulford Biological Laboratories, and scientific experts such as Brazil’s renowned herpetologist Dr. Afrânio do Amaral.

Baby snakes likely propagated for antivenin research.

Baby snakes likely propagated for antivenin research.

Unknown photographer, 1920s.

Courtesy of the United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Tela, Honduras. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Thus, a quarter century after UFCo acquired its first banana plantations—or bananeras —in Honduras, its research agenda ranged into the fields of ophiology (snakes) and toxinology (venom). This story of UFCo’s research on Central American serpents allows us the opportunity to explore an animal-centered history of this corporation’s presence in Honduras. It also opens the door to future research informed by a critical inter-American perspective on the history of mobile beings and products through the Caribbean Basin in the twentieth century.

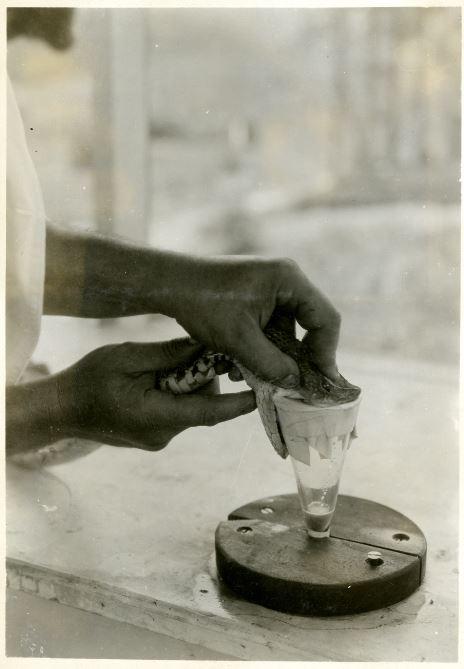

The snakes in question were primarily the Central American Rattlesnake (Crotalus durissus) and the Bothrops asper—a pit viper known by locals as the barba amarilla (yellow beard) who boasted a deadly bite. The latter, in particular, was a known presence on the bananeras, and workers who fell victim to their bites sought treatment from both plantation medical facilities and local healers. Scientists at the Experiment Station milked the venom from these snakes, and shipped it northward to the Mulford Laboratories, where it was in turn converted into experimental antivenins, and subsequently tested for efficacy by injection into horses.

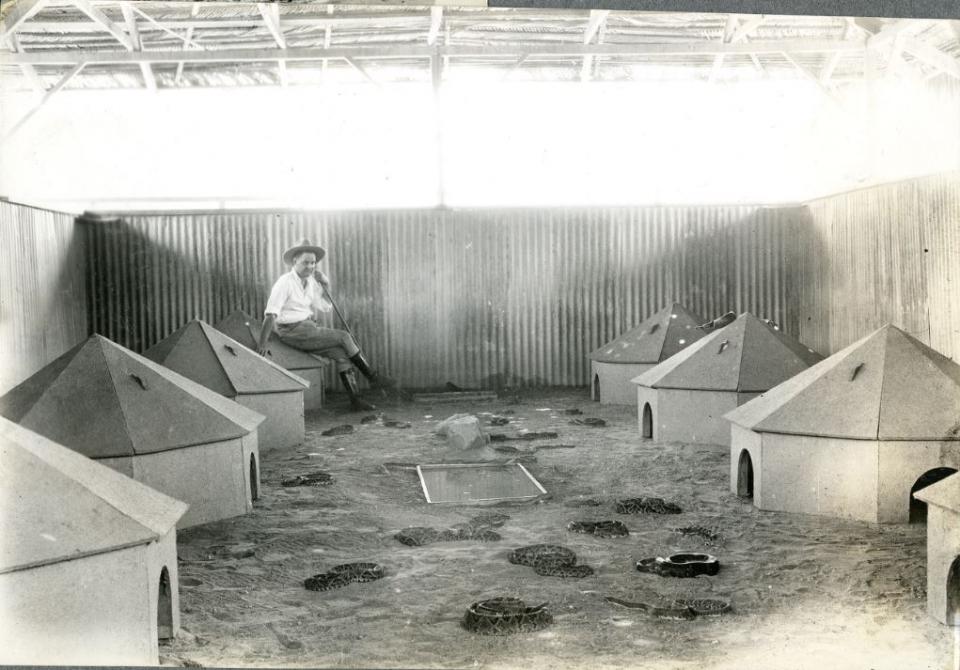

Interior of the United Fruit Company Serpentarium.

Interior of the United Fruit Company Serpentarium.

Unknown photographer, 1920s.

Courtesy of the United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Tela, Honduras. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Though generally mentioned only briefly in passing in historical accounts of UFCo, the presence of the Serpentarium’s residents in archival photographs of UFCo’s Honduran properties is prominent. Among thousands of UFCo photos in Harvard University’s Baker Library archives, seemingly endless photos of bananas and industrial equipment are broken up by a large stack of photos of the Serpentarium. Perhaps most arresting about the sudden appearance of hundreds of very live snakes is just that—their animacy. They are, as photographic subjects, acknowledged as living creatures in this extensive corporate archive in a way that other species often are not—including the humans at work at UFCo. Emblematic of this tendency to gloss over the presence of human workers in the fruit business is, for example, a 1950 photo of three jaunty bakers standing in a UFCo dining facility, grinning toothily at the camera, decked out in chef hats and aprons. A UFCo administrator took this image, labeling it simply and tellingly: “Bakery equipment.”

A snake being milked for venom at the research station.

A snake being milked for venom at the research station.

Unknown photographer, 1920s.

Courtesy of the United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Tela, Honduras. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

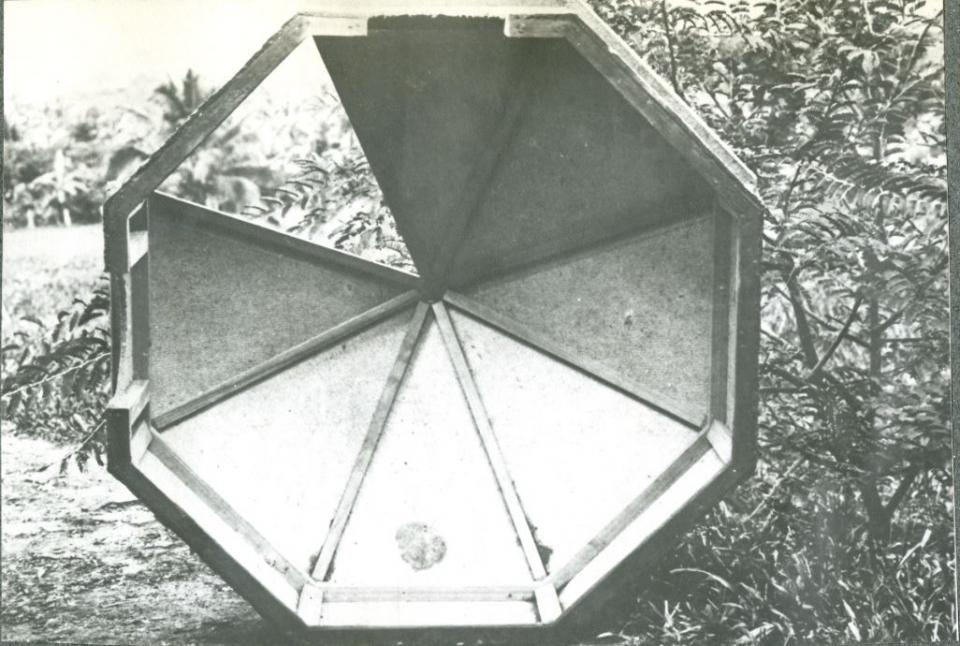

In contrast, archival photos of Lancetilla chronicle the lives of snakes in more intimate detail than any other living subjects (other than bananas, of course). Documentation included images of individual, octagonal-shaped houses built for snakes confined to the wooden and metal-screen walls of the Serpentarium. Arranged in parallel rows in eerie similarity to the human worker barracks, photos of the snake dwellings are more detailed than those of their human counterparts. Careful documentation of both the exterior and interior of the snake houses stands in marked contrast to the exterior-only view documented in the corresponding photographs of worker housing on UFCo bananeras. While historian Kevin Coleman’s compelling analysis encourages us to consider UFCo serpentariums as a visual canvas that served to reiterate discourses of modernization, considering an animal-centered history of these research facilities invites us to see snakes as connective linchpins for an array of lived historical experiences. They allow us to explore a narrative that encompassed roving scientific experts, UFCo laborers who risked their safety to collect snakes from the bananeras, and the inter-American itineraries of species like the barba amarilla, who frequently found themselves shipped off to laboratories and zoos across the hemisphere.

Interior of a snake dwelling at the Lancetilla Serpentarium.

Interior of a snake dwelling at the Lancetilla Serpentarium.

Unknown photographer, 1920s.

Courtesy of the United Fruit Company Photograph Collection, Tela, Honduras. Baker Library, Harvard Business School.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This represents the seed of a larger inquiry into the lives of people and animals bound together by hemispheric circulations of capital, labor, knowledge, and bio-products during the rise of UFCo. This brief foray points us toward possibilities for more critically analyzing various ways in which people experienced and interacted with the animals around them. It also sheds light on the possibility of an animal-centered history of the Lancetilla rattlers and pit vipers—two of so many species who lived amidst the shifting political-economic-ecological landscapes that accompanied the booms and busts of agribusiness.

How to cite

Balloffet, Lily Pearl. “Venomous Company: Snakes and Agribusiness in Honduras.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Spring 2020), no. 19. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/9042.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2020 Lily Pearl Balloffet

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Coleman, Kevin. A Camera in the Garden of Eden: The Self-Forging of a Banana Republic. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2016.

- Few, Martha, and Zeb Tortorici, eds. Centering Animals in Latin American History. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2013.

- Martin, James W. Banana Cowboys: The United Fruit Company and the Culture of Corporate Colonialism. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2018.

- Raby, Megan. American Tropics: The Caribbean Roots of Biodiversity Science. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

- Soluri, John. Banana Cultures: Agriculture, Consumption, and Environmental Change in Honduras and the United States. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press, 2005.