Repository–Mirror

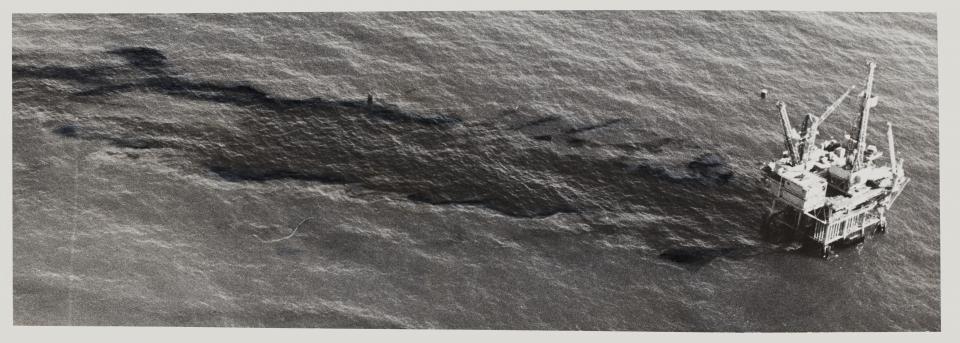

In 1969 a blow-out of an oil rig off Santa Barbara, California, outraged the public with its visible effects on shorelines up and down the coast and on seabirds and marine mammals. Coming just two years after the oil tanker SS Torrey Canyon wrecked off the western coast of England, the spill helped promote environmental concern in the US and Europe. Despite continuing worry about coastal oil spills and fear over radioactive waste disposal at sea, most marine scientists for decades after the spill adhered to the traditional dictum that the solution to pollution is dilution, continuing to view the open ocean as an appropriate repository for waste. Unknown photographer, n.d.

In 1969 a blow-out of an oil rig off Santa Barbara, California, outraged the public with its visible effects on shorelines up and down the coast and on seabirds and marine mammals. Coming just two years after the oil tanker SS Torrey Canyon wrecked off the western coast of England, the spill helped promote environmental concern in the US and Europe. Despite continuing worry about coastal oil spills and fear over radioactive waste disposal at sea, most marine scientists for decades after the spill adhered to the traditional dictum that the solution to pollution is dilution, continuing to view the open ocean as an appropriate repository for waste. Unknown photographer, n.d.

© Get Oil Out! (GOO!)

Used by permission

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Seascape showing female Ama divers from the Japanese coastal city of Ise harvesting abalone, a culturally and economically important fishery developed between the eighth and twelfth centuries. Before that, both men and women practiced breath-hold diving for subsistence gathering, and in the late nineteenth century the cultured pearl industry continued to employ Ama divers for an emerging tourist market. Woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada 歌川 国貞, c. 1830.

Seascape showing female Ama divers from the Japanese coastal city of Ise harvesting abalone, a culturally and economically important fishery developed between the eighth and twelfth centuries. Before that, both men and women practiced breath-hold diving for subsistence gathering, and in the late nineteenth century the cultured pearl industry continued to employ Ama divers for an emerging tourist market. Woodblock print by Utagawa Kunisada 歌川 国貞, c. 1830.

Courtesy of Cleveland Art Museum. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

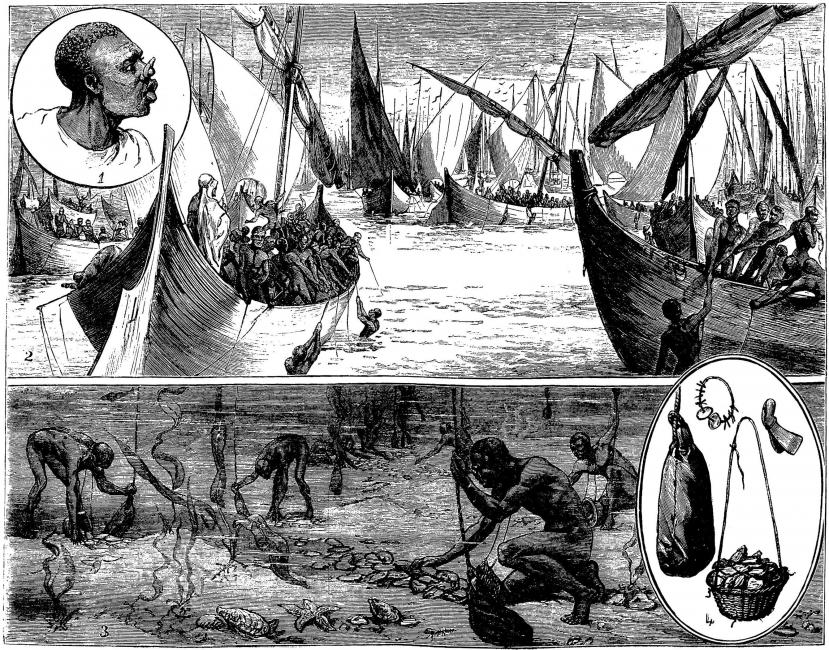

Evidence in shell middens and elsewhere tells archaeologists that early Homo sapiens and their hominid ancestors used aquatic resources whenever they were available. Commercial fisheries for herring, tuna, cod, and whales date back centuries or more. Many fisheries exerted profound effects on fish populations even before industrialization and mechanization. Fisheries sparked exploration of near and distant waters and contributed to the development of regional, then global economies. Yet subsistence fishing continued, and remains important today, in many places around the globe. People have not only viewed the ocean as a storehouse of raw materials and commodities but equally as a sink for waste. Despite this, many people through the twentieth century continued to see the ocean as a source of virtually limitless resources as well as a dumpsite of endless capacity. For some, this perception remains unchanged in the present, as reflected in oil and natural gas drilling, bioprospecting for pharmaceuticals, plans for seafloor mining, and the continued introduction of plastic and carbon into the oceans. Regardless of its use as storehouse or dump, the ocean as repository is experienced by users as volumetric space rather than a flat surface.

This strikingly unusual example of the Hudson River style of American landscape art, Edward Moran’s Valley in the Sea (1862), depicts an imagined panoramic view of the Atlantic seafloor. Probably commissioned in honor of the first successful transatlantic cable laying of 1858, this painting reflects the mid-century cultural discovery of the deep ocean that was also manifested by the popularity of marine natural history, beach holidays, yachting, maritime novels, and other ways that ordinary people engaged experientially and imaginatively with the sea.

This strikingly unusual example of the Hudson River style of American landscape art, Edward Moran’s Valley in the Sea (1862), depicts an imagined panoramic view of the Atlantic seafloor. Probably commissioned in honor of the first successful transatlantic cable laying of 1858, this painting reflects the mid-century cultural discovery of the deep ocean that was also manifested by the popularity of marine natural history, beach holidays, yachting, maritime novels, and other ways that ordinary people engaged experientially and imaginatively with the sea.

Edward Moran, The Valley in the Sea, 1862. Oil on canvas.

Courtesy of the Indianapolis Museum of Art. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The Hawaiian double-hulled voyaging canoe Hōkūleʻa, launched in 1975, is shown here arriving in Tahiti the following year after a transit using Polynesian navigation techniques. Subsequent voyages around the Pacific have contributed to cultural revival in Hawaii and in islands throughout Polynesia. Traditional voyaging reflects islanders’ identification of home as “seas of islands” in which the ocean forms part of their cultural and social space. In 2017, Hōkūleʻa completed a three-year circumnavigation blending traditional and modern technologies to promote Mālama Honua, which translates to “caring for our island Earth.” Photograph by Phil Uhl, 1976.

The Hawaiian double-hulled voyaging canoe Hōkūleʻa, launched in 1975, is shown here arriving in Tahiti the following year after a transit using Polynesian navigation techniques. Subsequent voyages around the Pacific have contributed to cultural revival in Hawaii and in islands throughout Polynesia. Traditional voyaging reflects islanders’ identification of home as “seas of islands” in which the ocean forms part of their cultural and social space. In 2017, Hōkūleʻa completed a three-year circumnavigation blending traditional and modern technologies to promote Mālama Honua, which translates to “caring for our island Earth.” Photograph by Phil Uhl, 1976.

Accessed via Wikimedia on 7 April 2021. Click here to view source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Whether we view the ocean optimistically as full of resources or fearfully as full of pollution, its opacity guarantees that we see reflected back from its surface in part what we bring to it: our fears, desires, ambitions, and preconceptions. Perceptions of the ocean depend on human assumptions, beliefs, and ideas as much as they derive from experiences with salt water and things that live in it. Different cultures with unique relationships to the sea generate distinctive notions of it. European immigrants to the New World viewed the ocean as a frightening wilderness. In contrast, the anthropologist Epeli Hau’ofa explains that people in Oceania view the same element as “seas of islands.” For them, the ocean forms part of their social and cultural space. Post–World War II embrace of the ocean as a “frontier” akin to the nineteenth-century United States West contributed to the tenaciously held view of the ocean as endlessly resilient in the face of human use. More recent media images of plastics in the sea or whales stranded, perhaps due to noise or other pollution, are reshaping perceptions of the human relationship with the ocean. The ocean as mirror helps explain how apparently contrasting uses, such as bridge or moat, can exist simultaneously. The repository–mirror pairing functions as a microcosm reflecting the cultural complexity of multiple, coexisting views of the world’s oceans.

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

Originally published in The Graphic: An Illustrated Weekly Newspaper, 1 October 1881: 356. Public domain.

Frontispiece to Edward Forbes, The Natural History of the European Seas (London: John van Voorst, 1859). Public domain.

Photograph by John Williamson, n.d. Public domain.

Originally published in J. E. Williamson, Twenty Years Under the Sea (Boston and New York: Hale, Cushman & Flint, 1936).

Photograph by Cl. Boulanger, 1913. Public domain.

Courtesy of the Freshwater and Marine Image Bank and the Washington Unversity Libraries. Click here to view source.

The 1945 short film Down to the Sea Again chronicles the use of fishing vessels during the Second World War for minesweeping, cargo carrying, and attacking submarines and airplanes, followed by their refit to fish again in peacetime. Postwar food shortages and hunger in Europe, and also in Japan, made the resumption of fishing a high priority, while record catches fueled optimism that modern science and technology would enable ever-growing use of the ocean’s resources. Many nations on both sides of the Cold War divide, viewing the oceans not only as a source of food and economic wealth but also as a politically strategic arena, subsidized the construction of fishing vessels such that the global fleet increased by 75 percent from the war’s end to the present. This fleet has overfished three-quarters of the world’s wild fish stocks and must cover increasingly large portions of the ocean to maintain global catches at a consistent level.

The short film Science in Fishing, released in 1958, features the Cornwall pilchard fishing vessel, The Chichester Lass, to demonstrate how fishers could use echo sounding technology, developed for anti-submarine warfare, to locate schools of fish hidden underwater. A large midwater trawl with a nylon net was deployed, capturing far more fish compared with the driftnets formerly used. This particular vessel was not fitted with an engine to haul the full net aboard, but power blocks came into increasing use in postwar fisheries for schooling species such as tuna, salmon, sardines, anchovies, and menhaden, paired with seine nets that could be set to surround a school found by sonar, making it easier to catch virtually every individual.

The original virtual exhibition features the short film Down to the Sea Again (1945). 3 min. 32. View the film online here.

The original virtual exhibition features the short film Science in Fishing (1958). 2 min. 42. View the film online here.