Literature

Militarized landscapes are a prominent theme in the increasing numbers of literary works that explore environmental justice themes. An important departure from the focus on “nature” and conservation that preoccupied many earlier environmental writers, environmental justice literature highlights the uneven distribution of risk factors spread by modern modes of production, transportation, waste disposal, and warfare. Recent novels, poems, memoirs, and performances highlight the environmental and social costs of militarization, and frequently draw comparisons between different groups and sites affected by US bases, expanding the groundwork for coalitions that cross spatial, temporal, and cultural boundaries.

Recent authors have adapted genres such as memoir, journalism, Gothic fiction, nature writing, and the noir thriller to expose how militarized landscapes such as Japanese-American internment camps, weapon test sites, and nuclear dumping grounds have laid waste to the US Southwest and the communities who live there (Beck 2009). Authors such as Leslie Marmon Silko, Terry Tempest Williams, Simon Ortiz, and James George dramatize the social consequences of nuclear testing in that region by describing experiences of war, cancer, and displacement. Williams’s memoir interweaves an account of her mother’s struggle with terminal cancer with a naturalist’s meditations on birdwatching in the environs of the Great Salt Lake. Only towards the end of the book does she provide the “unnatural” explanation for the numerous cases of cancer among her family and neighbors: they lived downwind from above-ground atomic tests conducted in the Nevada desert between 1951 and 1962.

In Ocean Roads (2006), George tracks an international cast of characters—a nuclear scientist, his cancer-afflicted son, a traumatized survivor of a napalm attack in Vietnam, an itinerant war photographer, and a scarred Japanese woman born on the day the US bombed Nagasaki—affected by the Trinity test and other instances of biological warfare. Japanese novelist Oda Makoto’s H: A Hiroshima Novel (1981) similarly connects the suffering of Hiroshima survivors with the fates of Hopi characters in the US Southwest such as Ron, who is affected by radiation poisoning after accidentally witnessing the Trinity test.

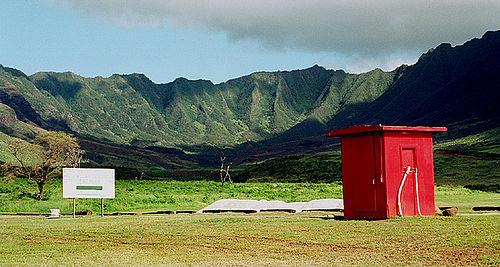

Although they are not as spectacular as nuclear explosions, non-nuclear training exercises also cause a range of problems throughout the US’s imperial territories. Connecting military testing in O’ahu with instances of nuclear contamination in the Marshall Islands, Chernobyl, and Three-Mile Island, Kiana Davenport’s House of Many Gods (2006) imagines a transnational environmentalist alliance between Hawaiian demilitarization activists and a documentary filmmaker from Russia suffering from radiation poisoning. The novel’s plot focuses on activist protests concerning Oahu’s Makua Valley, where thousands of farmers were evicted to make room for US war maneuvers and live fire training. In addition to damaging the land and air, causing noise pollution, and introducing accident risks, US military activities are linked to toxic waste disposal on sacred lands: “That’s where they openly burn spent ammunition. Spent rockets. Even Chinook choppers carrying nuclear-weapons parts that exploded up there on take-off. Pilots, their clothes, everything. All carefully incinerated, so there’s no proof…. And toxic poison is released in the smoke of those fires. We inhale it, ingest it. It’s in our fields, our food…” (Davenport 2006, 118). Although live ammunition exercises at Makua Valley were discontinued in 2004, the army continues to “use the military reservations in different ways” and will “decide whether to resume live-fire training once [environmental impact] studies are complete.”

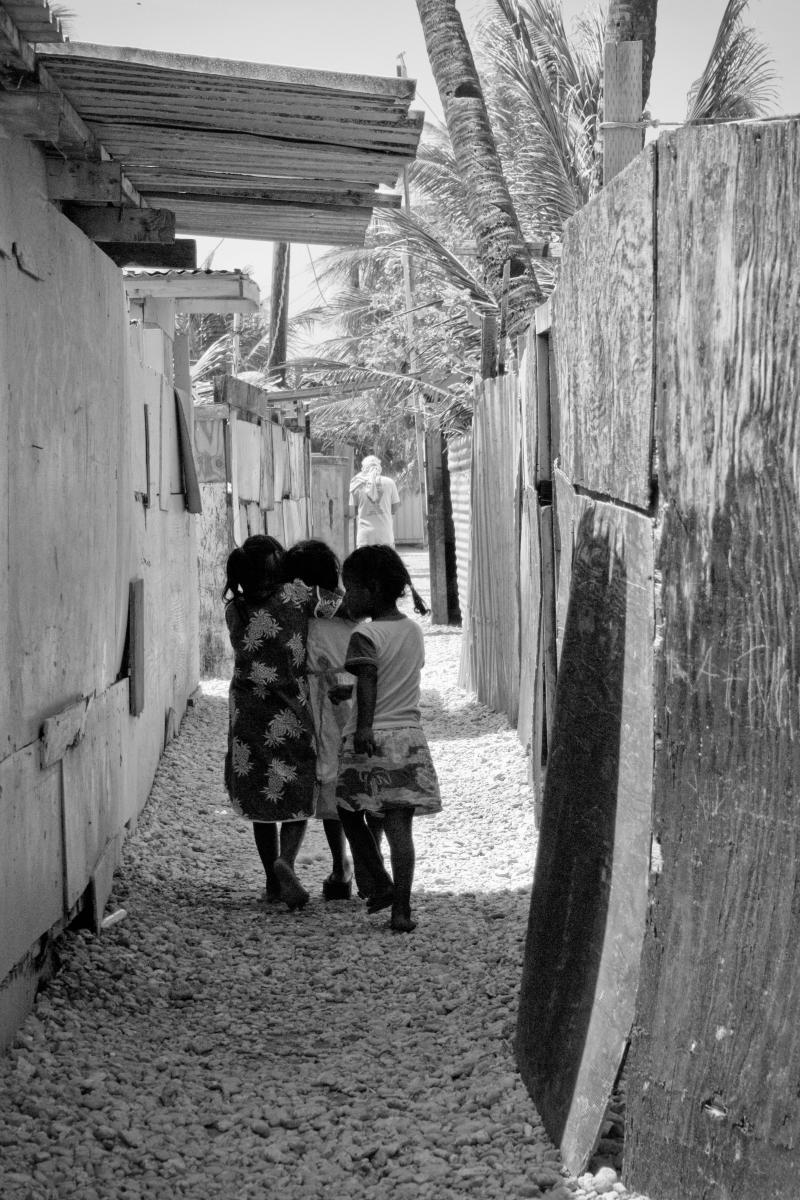

Makua Valley military testing area, Oahu, Hawai’i.

Makua Valley military testing area, Oahu, Hawai’i.

Photo by Meutia Chaerani - Indradi Soemardjan.

View source.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

In Melal: A Novel of the Pacific (2002), longtime Kwajalein resident Robert Barclay dramatizes the geographical inequities of the relationship between two islands in the Marshall Islands group: Kwajalein and Ebeye. Whereas Kwajalein—a command base for US nuclear trials and the Nike-Zeus anti-ballistic missile testing program—provides comfortable housing, affordable food, and healthy infrastructure for a population primarily consisting of US military personnel, Ebeye is densely populated by refugees relocated from several nearby islands (including Kwajalein) to make space for nuclear and anti-ballistic missile tests. In addition to describing the pollution, filth, poor sewage, unsafe fisheries, overcrowding, suicides, and radiation-induced cancer and miscarriages suffered by Ebeye’s inhabitants, Melal details the poisoned, devastated spaces encountered by two Marshallese children who resolve to camp out on their ancestral island of Tar-Woj in spite of US missile tests. The novel’s title—a Marshallese word meaning “playground of demons”—could refer to either the children’s ancestral island or the island to which their family has been resettled.

Even in the absence of training drills and weapons testing, US bases cause a range of problems for neighboring communities. In Memories of My Ghost Brother (1997), Heinz Insu Fenkl details his experiences growing up on and near a US army base in South Korea. In addition to documenting black market operations, suicides, sex work, racism, domestic violence, and other tense relations between Koreans and GIs, Fenkl (1997, 249) describes an impoverished and noxious environment: “narrow alleys running with sewage and piss and wafting with a stench so awful that it gagged you.” In the environs of the ASCOM base, Korean and mixed-race children play on slippery elevated train tracks, near the sewer canal, among dust, feces, and live ammunition: “I remembered hunting for artillery brass one afternoon near a place the GIs called Mickey Mouse Village, finding wads of C4 plastic explosive, manual fuses, unexploded shells. Earlier that week some boy had dug out a shell and dropped it on a stone, and he had blown himself to pieces, scattering fragments of himself so far they could not gather him together again to hide under a straw mat” (Fenkl 1997, 248).

While these memoirs and novels dramatize how military activities affect family life and character development, poetry can provide more abstract reflections on the connections between militarization, culture, and language. Juliana Spahr’s thisconnectionofeveryonewithlungs (2005, 10) considers interconnectedness between bodies, things, and molecules (“everyone mixing / inside of everyone with nitrogen and oxygen and water vapor and…titanium and nickel and minute silicon particles from pulverized / glass and concrete”) in the global contexts of the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. Located in Hawai’i—on an island where “thirty Navy and Coast Guard warships,” “eighteen nuclear submarines,” “five destroyers,” and “two frigates” are docked, Spahr’s speaker contemplates how everyday experiences of landscape, language, and love are intermixed with military force: “the beach on which we reclined is occupied by the US military so every word we said was shaped by other words, every moment of beauty occupied” (2005, 67). The poet’s idyllic thoughts of island birds become entangled with the American ships and airplanes deployed from Hawai’i, which would materially contribute to the “shock and awe” campaign waged against combatants and civilians alike on the other side of the planet.

Craig Santos Perez’s multivolume poem from unincorporated territory (2008, 2010) meditates on the geographical and social consequences of Guam’s colonial status as both an “unincorporated territory” subject to US rule and a key site for the projection of US military power across the Pacific. Incorporating numerous maps that illustrate Guam’s strategic location and the locations of its bases, Perez’s volumes consider the legacies of Spanish, Japanese, and US colonialism alongside the ongoing environmental harm wrought by US militarization. Perez uses the invasive brown tree snake—first brought to Guam by US military cargo ships—as a symbol of invasion and environmental harm: “About 100 times a year, a brown tree snake will scale a power line or transformer, electrocuting itself and causing a power outage that may span the entire island. At present, Guam has lost all its breeding populations of seabirds, 10 of 13 endemic species of forest birds, 2 of 3 native mammals, and 6 of 10 native species of lizards. Also, there have been over a 100 [sic] of infant deaths reported in the last 50 years” (2008, 93). While describing efforts to repair Chamorro language and cultural practices in the wake of colonial devastation, from unincorporated territory [saina] provides an excerpt on the environmental impacts of US bases from Perez’s own testimony before the UN Special Political and Decolonization Committee. To emphasize Guam’s lack of official status in the UN and its erasure in national discourse, Perez reproduces his testimony under erasure:

this hyper militarization…will severely devastate…our environmental, social, physical and cultural health. since world war two, military dumping and nuclear testing has contaminated the pacific with pcb’s and radiation. in addition, pcb’s and other military toxic waste have choked the breath out of the largest barrier reef system of guam, poisoning fish and fishing grounds. as recently as july of this year, the uss houston, a u.s. navy nuclear submarine home ported on guam, leaked trace amounts of radioactivity into our waters(2010, 45, 60).

Bibliography:

Barclay, Robert. Melal: A Novel of the Pacific. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002.

Beck, John. Dirty Wars: Landscape, Power, and Waste in Western American Literature. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

Davenport, Kiana. House of Many Gods. New York: Ballantine Books, 2006.

Fenkl, Heinz Insu. Memories of My Ghost Brother. New York: Dutton, 1997.

George, James. Ocean Roads. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 2006.

Oda Makoto. H: A Hiroshima Novel. Translated by D. Hugh Whittaker. Tokyo: Kodansha International, 1995.

Perez, Craig Santos. from unincorporated territory [hacha]. Kane’ohe, HI: Tinfish, 2008.

———. from unincorporated territory [saina]. Richmond, CA: Omnidawn Publishing, 2010.

Spahr, Juliana. thisconnectionofeveryonewithlungs. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

Williams, Terry Tempest. Refuge. New York: Pantheon, 1991.

- Previous chapter

- Next chapter