Laundry and female laundry workers

“Eventually they arrive at the rivulet, which is as noisy and clattery as they are. Each of them picks a spot and moments later they begin their routine. Their songs and laughter break the steady cadence of the rolling crystalline waters and the sleepy hum of insects hiding below leaves or resting on the riverbanks. The constant smacking of clothes against rocks is reminiscent of alternating hammers on a forge. Playful taunts can be heard flying from wash spot to wash spot like agile arrows. Murmurs intertwine with sweet ease and people’s lives become known and commented on while the clothes being washed sully the crystalline rivulet.”

—José Antonio Gutiérrez Ferreira. “Cronistas de El Gráfico—El Lavadero.” El Gráfico, 19 May 1923, 704. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

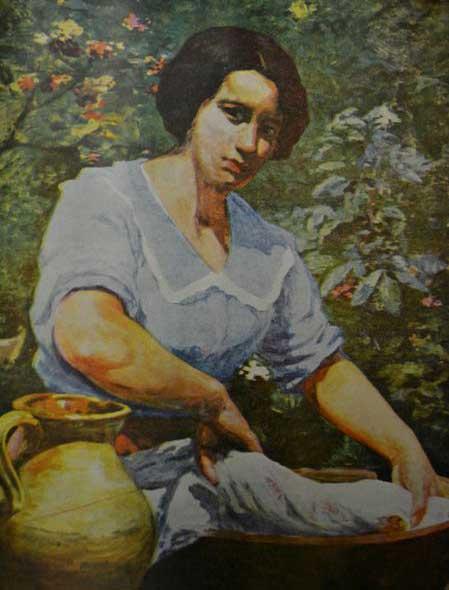

Luis Alberto Acuña, Lavanderas (Female laundry workers), 1910

Luis Alberto Acuña, Lavanderas (Female laundry workers), 1910

All rights reserved. Acuña, Luis Alberto.Lavanderas (1910). Courtesy of Museo de Bogotá. Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio Cultural.

Washerwomen washing clothes in small ponds built on the bank of a river. They are surrounded by clotheslines and baskets to carry the laundry.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, most families in Bogotá had their laundry washed by female laundry workers. These women often dedicated themselves to this kind of work as a means of supporting their families. Female laundry workers generally came from lower working-class backgrounds and were characterized as being part of a group of women entering the paid labor force. They were also perceived as forming part of a distinct collective that came to symbolize a relationship between water, washing, and womanhood. On occasion, this relationship between environment, work, and gender identity created a liberating environment for socializing, in which female laundry workers could talk, laugh, sing, and smoke cigarettes together. Through these social interactions they created a sense of solidarity and camaraderie, and to some extent alleviated the hardships and sacrifices they faced in their daily lives. These female laundry workers and their working conditions inspired artistic expressions including paintings, photography, music, and literature.

“On the shores of rivers and rivulets you can see them kneeling as they suffer under the unforgiving elements. For long hours they smack clothes against large river stones, enduring the cold and humidity that attack their hands and arms. Their entire lower bodies are soaked from the contact with the wet ground. A noted hygienist commented on the characteristic look of a female laundry worker’s hands: deformed, swollen, and reddish raw in appearance. Their skin is macerated by the cold river water and the alkaline lyes or soap. Their hands are always wrinkled from the water, and when they dry their skin is cracked, and flaky. Their fingers are usually retracted and deformed and they generally have calluses all along their hands and forearms.

The two women that stake out the first two spots on opposite edges of the river wash with clean water, every successive spot downstream gets increasingly dirty and polluted water as the soiled clothes release their filth into the flowing stream. By the time the water gets to the fifteenth or twentieth spots downstream the water is completely unacceptable and undoubtedly contaminated. This makes clothes susceptible to a variety of contagious pathogens.”—Tiberio Rojas and Pedro M. Ibáñez. “Contribución al Estudio de la Higiene Pública de Bogotá.” Registro Municipal de Higiene, 20 July 1919, 14. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

Saúl Ordúz, Lavanderas, 1950

Saúl Ordúz, Lavanderas, 1950

Female laundry workers scrubbing clothes against the rocks of a calm river. Location was an important issue for female laundry workers. In certain spots, they could enjoy rocks better suited for scrubbing, and cleaner water, which meant easier working conditions and more rewarding results. The appropriation of the environment was also important in laundry work. Barbed wire fences used as clotheslines show this appropriation, but also evidence the role of sun and wind for traditional laundry.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Museo de Bogotá. Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio Cultural.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The climatic conditions caused by Bogotá’s altitude—and the fact that the city is located at the foot of an Andean Mountain chain—conditioned the daily life of the female laundry workers. They would begin their workdays in the typically chilly early-morning weather of Bogotá, carrying large loads of laundry that had to be soaped, scrubbed, and washed along the edges of local rivers and rivulets. The San Francisco and San Agustín rivers sprang up from the Eastern Mountains and flowed through the central area of the city itself, picking up waste from homes and businesses on its way downstream. This forced the female laundry workers to take their laundry to water sources that were cleaner, but further away, like the San Cristóbal River at the southern periphery of the city or to the Arzobispo River in the north. The water from all of these rivers was cold to the point of freezing and the women’s hands were often irritated, and even deformed, as a result of the combined effects of the repetitive stress of their labor and cold water temperatures. Often these hardships were endured in vain because the dirt and filth from the laundry being washed further upstream—these women had arrived earlier and as such had the advantage of picking better spots—would flow with the current and soil the laundry being washed downstream. This evidently created a competitive atmosphere among the female laundry workers to obtain the more privileged spots upstream, alluding to the perpendicular relationship between the rivers and the city, whereby people would move to higher regions in order to have access to cleaner water.

The treks upstream to the sources of the rivers were long, the loads of laundry were heavy, and joint pain and chronic skin problems became commonplace for the female laundry workers. Mothers had to leave their children at home while they worked, and so would suffer the condemnation of public opinion from a society that passed judgment without understanding the nature of the problem. Worse still, the daily sacrifices endured by the female laundry workers were all but ignored when engineers and physicians, promoting hygiene in the early decades of the twentieth century, accused them of endangering the health of urban citizens by using the rivers to wash the clothes of those suffering from contagious waterborne illnesses such as typhoid fever.

Meanwhile, the female laundry workers worried about the damage caused to their laundry by pollution and the negative effects this had on the quality of their work. They often complained about mining companies located higher in the Eastern Mountains that polluted the rivers with their industrial waste. Letters were repeatedly sent to the mayor by groups of female laundry workers, requesting a solution to pollution of the San Cristóbal River caused by lime mines located on a stretch of land called El Delirio, owned by the Copete brothers. The municipal government forbade the brothers from polluting the river, but the mines continued to be intermittently active until the municipal government was able to negotiate purchase of the land in 1911. This again demonstrates the privileged situation enjoyed by those who dominated access to water higher upstream, and sheds light on the cohesion and power that female laundry workers demonstrated collectively when it came to defending their right to work.

“Mr. Governor,

the undersigned female laundry workers of the city, on behalf of our colleagues, hereby address this letter to you. We respectfully wish to make manifest that for some time we have used the San Cristóbal River to wash the clothes entrusted to us. Through this work we earn our daily living. For more than a month we have not been able to wash because the river water becomes muddied as it flows downstream. We discovered that this is caused by mining being undertaken by gentlemen named Copete on the riverbanks. This is to our detriment because it robs us of our daily bread, as we cannot opportunely wash the clothes we have been charged with. We are aware that you are the authority entrusted with the care of the rivers. We therefore express our formal legal complaint and request for your aid and protection.

(Signed) Betsabé Cicedo Z., Mercedes Díaz, Simona Barbosa, Leonilde Rodríguez”—Quoted by Antonio Sánchez Gómez. Manos al Agua: Una Historia de Aguas, Lavado de Ropas y Lavanderas en Bogotá, 137-8. Bogotá: Universidad Nacional de Colombia, 2010. Taken from “Proyectos de acuerdo”, 1910. Collection Concejo de Bogotá, Archivo de Bogotá, Volumes 604–3570, 253–4. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

The concern for clean water—shared by both the female laundry workers and sanitary reformers—led to the adoption of technological advances for laundry that would transform the relationship between population and water throughout the twentieth century.

Manuel H. Rodríguez Corredor, Lavaderos Comunales, 1960

Manuel H. Rodríguez Corredor, Lavaderos Comunales, 1960

Women wash clothes in public laundry washbasins made from cement. Each washbasin has a rough surface to scrub clothes and a tank filled with water from a faucet. The public laundry washbasin was an interesting technoscientific device facilitating the transition from the collective tradition of washing clothes in rivers towards the private ritual of the home washing machine.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Margarita Rodríguez Rodríguez.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

In an attempt to improve the working conditions of the female laundry workers and ensure a healthier water supply for the city, the municipal government installed public laundry washbasins made out of stone and cement. Wealthier families living in large houses in residential neighborhoods could afford to have laundry washbasins installed in their homes—taking advantage of being connected to the municipal aqueduct—and usually had ample space in courtyards for a laundry room. The public laundry washbasins made it possible for the female laundry workers to avoid direct contact with river water, which was channeled through a network of tanks, pipes, and faucets into the public laundries. Doing laundry at home became a social trend that paralleled the physical separation between the river and the female laundry workers. The socializing once enjoyed by female laundry workers on the riverbanks now took place in the collective spaces created by the public laundries and their rows of washbasins; meanwhile, washing laundry at home had the opposite effect, as it became a much more private and solitary affair.

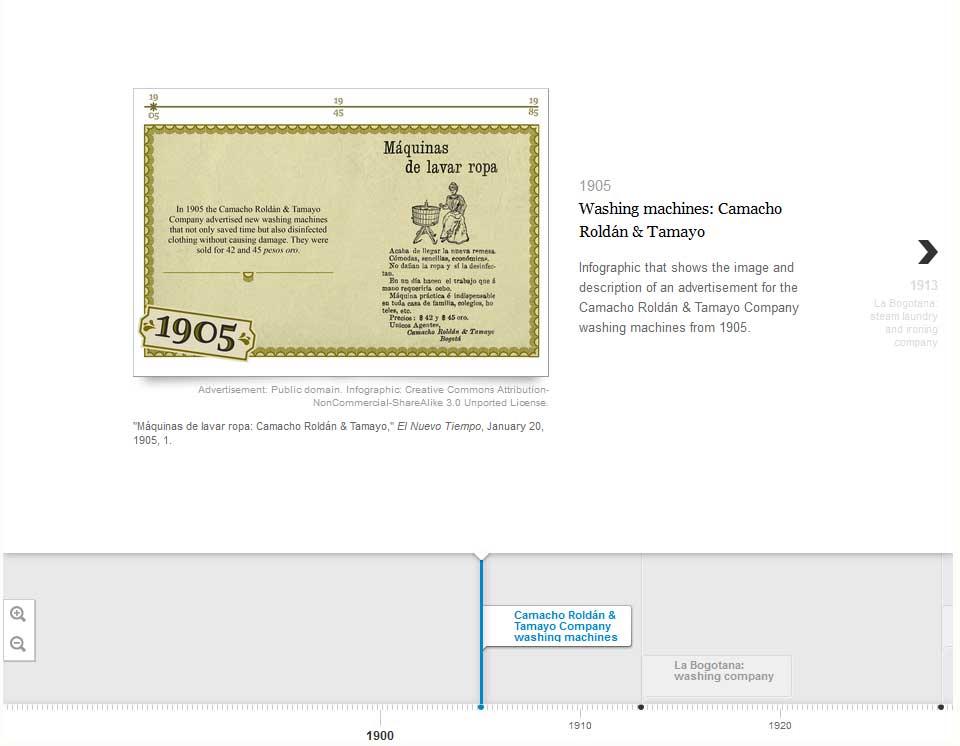

Washing machines, understood here as technological devices that accentuated the separation between female laundry workers and the rivers, used dials, hoses, tubs, pumps, and agitators to scrub, wash, rinse, and spin-dry clothes. In effect this meant technology substituted the more traditional method of hand washing: river stones to smack the garments, a natural flow of water to wash out the soap, and improvised lines to hang garments to dry in the wind and sun. These new machines, which were introduced in Bogotá during the first decade of the twentieth century, used water that was piped in through the municipal aqueduct and then discarded through a precarious drainage and sewage system. Washing machines were manually operated at first, but soon gasoline, kerosene, and electrically-powered models became available. Power came from the El Charquito Hydroelectric Power Plant, inaugurated in 1900 by the Electric Energy Company of Bogotá (Compañía de Energía Eléctrica de Bogotá) to take advantage of the hydroelectric power available from the Bogotá River nearby the Tequendama Waterfall (Salto de Tequendama).

Although sometimes instruction manuals were difficult to decipher for refined housewives and tidy maids, who were increasingly responsible for laundry, washing machines became an essential appliance for a well-equipped home in the mid-twentieth century. Advertisements in the local newspapers made sure to popularize and promote the need for washing machines, which were imported by American companies like General Electric, Westinghouse Electric, and Hurley Machine, and some European companies such as Philips. Advertisements for washing machines and for a variety of soap brands—including Lux, Blancol, and Oro—promised to eliminate dirt, protect delicate garments, and to be efficient. This brought into question the traditional practices and images of the humble female laundry workers who wore their distinctive straw hats to protect themselves from the weather as they crossed the city with their loads of laundry to wash in the rivers. Parallel to technological innovation, an increasingly private and elitist attitude towards laundry led to the general conception of a modern society that was separate from its natural environment, and the perception of water as a resource whose origin and ultimate destination was almost completely unknown.

“A good number of improvised clothes lines, draped with clothes of all sizes and colors, were the happy preamble to our first visit to the legendary laundry in the Diana Turbay neighborhood. A concrete slab measuring two meters in length and supported by three columns of cinder blocks and bricks rests on a rustic cement floor. On top rests a mid-size tank where the water that falls through a thin tube is stored. The tube itself emerges horizontally from the small mountain chain, which is both landscape and wall to this place.”

—María Isabel Arias Cadena. “Las Lavanderas del Diana Turbay.” In Talleres de Crónica. Memorias del Agua en Bogotá: Antología, edited by Mariluz Vallejo Mejía, 184. Bogotá: Banco de la República, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Alcaldía Mayor de Bogotá, Archivo de Bogotá, 2011. Accessed 25 March 2013. (Quotation translated by the authors of the exhibition.)

Daniel Rodríguez, Calle 33 con Cra. 3, 1940

Daniel Rodríguez, Calle 33 con Cra. 3, 1940

Clothesline in La Perseverancia neighborhood, a working-class neighborhood located on the Eastern Mountains of Bogotá. This neighborhood, created to provide housing for the workers of the locally famous Bavaria Brewery, ended up being one of the most politically active urban areas during the twentieth century.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Museo de Bogotá. Instituto Distrital de Patrimonio Cultural.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

These parallel processes undoubtedly transformed the social dynamics of laundry in Bogotá, but did not result in the complete disappearance of female laundry workers, and instead diversified the composition of the group. Along with those who washed clothes in the rivers to earn a living, there were now housewives doing laundry at home, concerned about the cleanliness and care of their clothes, and there were maids who clumsily learned how to use the growing number of new washing machines. Aside from women, there were companies specializing in laundry delivery services that took advantage of the difficulty some people had with the machines to offer a door-to-door service: they would pick up a person’s dirty laundry and return it the next day clean and in good condition. Ironically, this was simply a more institutionalized and updated form of the same service that was provided by the old female laundry workers. The persistence of female laundry workers as an urban collective meant the retention of the public laundry washbasins; indeed, these washbasins they still exist and function in Bogotá today despite the ample coverage provided by modern public water infrastructure and the mass use of washing machines in homes. Such is the case with the public laundry washbasins located in the Diana Turbay neighborhood in the southeastern part of the city, where women often take advantage of the public cement washbasins and the free and clean water channeled from the Chiguaza Rivulet to wash their clothes. This saves them money that they would otherwise have to spend on water bills, or in other cases compensates for their lack of means of washing clothes at home.

Female laundry workers in Colombian art

In Colombia, the artistic works inspired by the image of the female laundry worker influenced the creation of characters in nineteenth-century literary costumbrismo, such as the novels Manuela and Aguinaldos en Chapinero, published in 1889 and 1873, respectively, both authored by Eugenio Díaz Castro.

Colombian music has also recognized the romantic potential of female laundry workers, who not only reflect ingrained popular customs but embody contradictory feelings of suffering, joy, submission, and liberation. This sentiment is expressed in songs like La Lavandera, written in the Afro-Colombian bullerengue style from the Caribbean coast and sung by the popular folklore singer Petrona Martínez. Likewise the song Las Lavanderas, written in the traditional Andean pasillo style—played as duet by a guitar and a Colombian tiple guitar—and interpreted by renowned duos such as Garzón y Collazos and Silva y Villaba. The fact that such dissimilar music styles from two very different areas in Colombia have given rise to songs dedicated to the same topic is testament to the inspirational power of female laundry workers.

Visual artworks inspired by female laundry workers include photography by renowned Bogotá photographer Manuel H. Rodríguez; paintings by diverse Colombian painters like Domingo Moreno Otero, Miguel Díaz Vargas, Eugenio Zerda, Segundo Agelvis, Luis Alberto Acuña, Andrés de Santa María, Humberto Chávez and Saady González; and performance art such as the controversial piece by artist and architect Simón Hosie, who in 2009 took over Bolívar Square in Bogotá by installing the house of a fictitious female laundry worker.

Domingo Moreno Otero, La lavandera, 1910

Domingo Moreno Otero, La lavandera, 1910

Oil painting by the Colombian artist Domingo Moreno Otero (1982-1948), known for his depictions of landscapes and customs in the early twentieth century. This painting shows a female laundry worker holding a basket with laundry on the bank of a river. The beautiful rural landscape, and the woman’s gaze lost in the horizon, remind bucolic feelings that once were associated to the river, now having become a female working place.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Marina González de Cala.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Eugenio Zerda, “Lavanderas”, El Gráfico, June 23, 1923, cover

Eugenio Zerda, “Lavanderas”, El Gráfico, June 23, 1923, cover

Drawing by the Colombian artist Eugenio Zerda (1879-1945), showing a group of female laundry workers with hats and headscarves rubbing clothes against the rocks of a river. This drawing was published in a cover of the magazine El Gráfico, which along with the magazine Cromos are important sources for the graphical history of Bogotá.

All rights reserved. Courtesy of Jorge Enrique Angarita Zerda.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Soaps and washing machines: The conquistadors of laundry

The twentieth century revolutionized the way clothes were washed owing to the steady influx of new machines and cleaning products. As discourse on public health grew stronger in Bogotá, new brands that advertised solutions for cleanliness at home flourished. Advertisements for innovative soaps and manual, gasoline, or electric washing machines multiplied in high-circulating national newspapers such as El Tiempo, all promising efficiency, garment protection, and speed. They were clearly aimed at female members of the public who were progressively gaining access to the labor force and who consequently had less time for the typical chores of a housewife.

Nevertheless, such technological innovation did not result in the complete disappearance of female laundry workers. Instead they dissipated into the urban scene while the composition of their group diversified. This had adverse effects for the cohesion of the female laundry workers as a collective, weakening their influence on public life. In fact, the expansion of aqueduct and sewage network infrastructure—which took off with the creation of the Municipal Aqueduct Company of Bogotá (Empresa Municipal del Acueducto de Bogotá) in 1914—had the effect of displacing riverbank and public washbasin laundry to the private sphere where housewives and maids took over the daily task of washing clothes. Laundry slowly became a middle and upper class chore—despite having previously been considered a job for lower working class women—but it was still considered a distinctly feminine chore.

As the twentieth century progressed, female laundry workers had to face new challenges from the increasing technological complexity of laundry. Attempts to overcome these difficulties included public announcements containing instructions for complex imported washing machines. Home delivery laundry services were offered in response to the frustrations of washing at home, and advertisements for efficient machines and miracle soaps became common. New improvements in water infrastructure, along with competent machines and cleaning products, led to a separation between society and nature, even though the environment was involved to some extent during each stage of development that led up to modern methods of washing.

Laundry news:

A timeline of washing machine, laundry company, and soap advertisements

(click here to view timeline in a new window)

The original virtual exhibition features an interactive timeline showcasing washing machine, laundry company, and soap advertisements.

Click on this timeline to view several historical washing machine, laundry, and soap advertisements.

Click on this timeline to view several historical washing machine, laundry, and soap advertisements.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

All timeline infographics have been created by Tangrama (Mónica Páez Pérez and María José Castillo Ortega)

in 2013 under a CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 license.