In 1969 the process began that led to the creation of Kouchibouguac National Park along Canada’s Atlantic coast in the province of New Brunswick. In line with the practice at the time in many parts of the world, 1,200 residents were removed from their lands so that nature could be shown to visitors without a permanent human presence. Visitors were encouraged to believe that no human hands had been involved with presenting the park’s spectacular beaches and its dunes just off the coast, as well as its bogs, marshes, and forests.

View of Kouchibouguac’s coastal vegetation

View of Kouchibouguac’s coastal vegetation

2013 Ronald Rudin

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Beach at Kouchibouguac

Beach at Kouchibouguac

2013 Ronald Rudin

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

Over forty years after the creation of Kouchibouguac, it is known as much for how the former residents were treated as for its “natural” attractions. These residents were poor but had developed a distinctive way of life based upon the resources of the region. However, government officials only saw them as people requiring “rehabilitation,” to use the expression of the day, and so the creation of the park was seen as an opportunity to move these individuals elsewhere and transform them into more productive citizens.

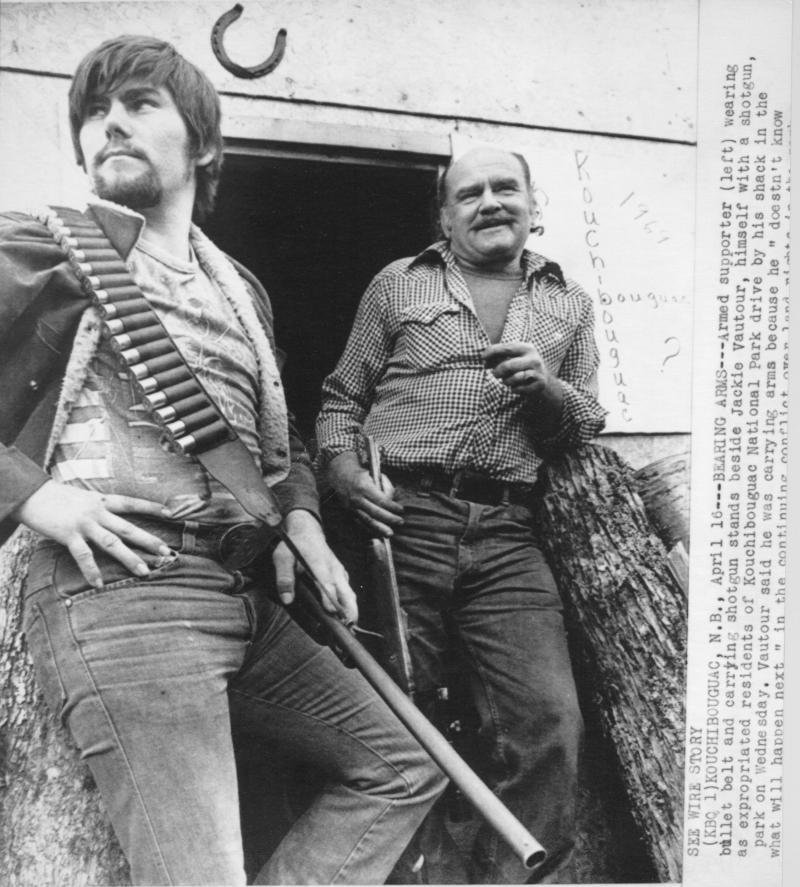

Having decided that the residents could be easily manipulated, officials did not expect any resistance. But over the course of the 1970s, the park was shut down on several occasions by residents who were unwilling to accept the meager compensation that they had been offered both for their lands and for the loss of their right to fish in park waters.

Jackie Vautour (on the right) squatting on his land (28 March 1980)

Jackie Vautour (on the right) squatting on his land (28 March 1980)

All rights reserved © Centre d’études acadiennes Anselme-Chisasson, E-8377

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This resistance was encouraged by the fact that the vast majority of the residents were Acadians, the French speakers of the Atlantic region of Canada who had been removed from their lands—deported—in the eighteenth century by British forces on the eve of the Seven Years’ War. Few Acadians ever returned from the deportation, but some escaped their captors and ended up living in regions such as the one where Kouchibouguac National Park is now located. Accordingly, when they were forced from their properties for the creation of a park, many saw it as a “second deportation.”

This struck a chord with Acadian artists, who have told the story of the seven communities that were destroyed through a variety of media: from film to poetry, and from theater to sculpture. And the leader of the resistance, Jackie Vautour, who refused to leave his land until he was forced out by the destruction of his home, ultimately returned to squat on his land where he remains today, a folk hero for Acadians who resented being deported once again.

The Fontaine family returns to its expropriated land (17 April 1980)

The Fontaine family returns to its expropriated land (17 April 1980)

All rights reserved © Centre d’études acadiennes Anselme-Chisasson, E-8379

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The Canadian government had been involved in removing people to create national parks on many occasions going back to the early twentieth century. In several other cases there were protests, but nothing like the organized resistance at Kouchibouguac, which led to the abandonment of the practice of forced removal by the mid-1970s.

How to cite

Rudin, Ronald. “Removing the People: The Creation of Canada’s Kouchibouguac National Park.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (2013), no. 17. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. https://doi.org/10.5282/rcc/5646.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

2013 Ronald Rudin

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on the images to view their individual rights status.

- Campbell, Claire, ed. A Century of Parks Canada, 1911–2011. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2011.

- Jacoby, Karl. Crimes Against Nature: Squatters, Poachers, Thieves and the Hidden History of American Conservation. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001.

- Rudin, Ronald. “Making Kouchibouguac: Acadians, the Creation of a National Park, and the Politics of Documentary Film during the 1970s.” Acadiensis 39, no. 2 (Summer/Autumn 2010): 3–22.

- Rudin, Ronald. "Kouchibouguac: Representations of a Park in Acadian Popular Culture." A Century of Parks Canada, 1911–2011, edited by Claire Campbell, 205–33. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, 2011.

- Rudin, Ronald. "The First French-Canadian National Parks: Kouchibouguac and Forillon in History and Memory." Journal of the Canadian Historical Association 22, no.1 (2011): 161–200.

- Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1998.