ONLY TO BE USED IN “BOTANIZING THE BORDERLANDS” BY LANCE THURNER:

ONLY TO BE USED IN “BOTANIZING THE BORDERLANDS” BY LANCE THURNER:

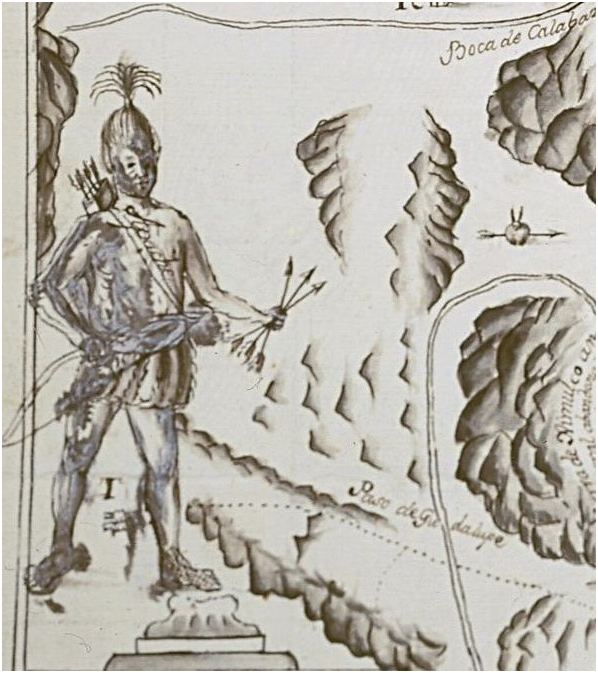

© Ministro de Culture y Deporte. Archivo General de Indias, AGI, MP-Mexico, 410TER (detail).

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

“I am so miserable here that if God doesn’t fix this by giving me another posting I think I’ll mutiny,”—bemoaned Ignacio de León y Pérez, resident pharmacist and botanist at Santa Rosa garrison, located near the present-day Texas border, where in the late eighteenth century the Spanish empire yielded to indigenous dominion. It wasn’t supposed to be this hard to be a young man of science bringing enlightenment to the edge of civilization. In fact, as a young “Indian” man of science his superiors back in Mexico City thought he would have certain advantages. But in the 1790s, in the borderlands where Lipan, Mescalero, and Gila Apache battled to maintain their autonomy, cosmopolitan ideas of indigeneity and science met their limits (de León y Pérez 28 March 1793 & 30 April 1793).

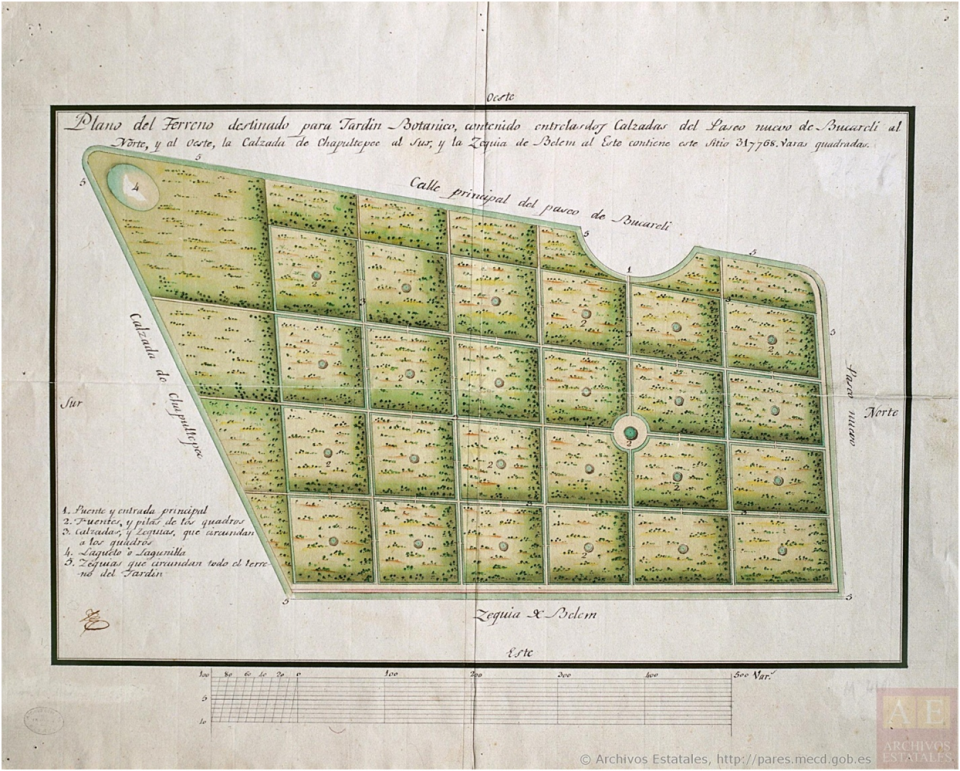

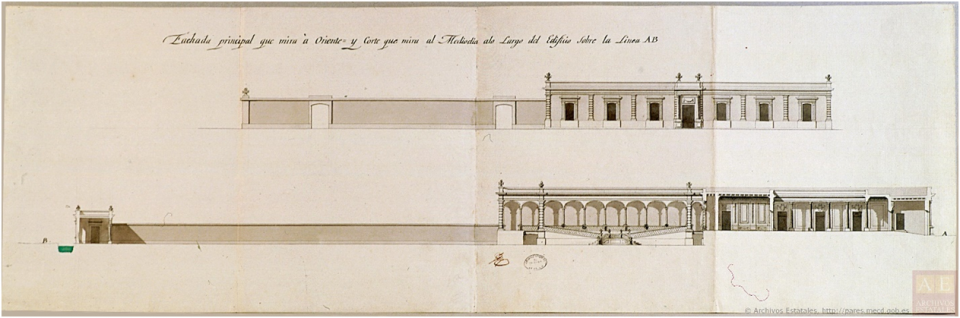

León y Pérez was a guinea pig and model for enlightenment reform. To prove to skeptics the improvability of native minds, Martín de Sessé and Vicente Cervantes, directors of the Royal Botanical Expedition to New Spain and its offshoot, the Botanical Garden in Mexico City, admitted him two years prior into their training program. There, León y Pérez excelled: “He has succeeded in ratifying the high hopes of the Director and Professor of this School, regarding the progress that [indigenous] Mexicans could reach in regards to botany [suggesting] they may aid in the perfection of the garden or be given occasion to travel to extend the light and distribute their knowledge” (Valdés 1794: 704). After León y Pérez demonstrated his mastery of Linnaean binomial nomenclature to the public, Sessé commissioned him as an official botanist while he served in the frontier army in the wars against the Ndé, known to the Spaniards and ever since as the Apache (Valdés 1794: 705).

License exclusive to Lance Thurner’s Arcadia article “Botanizing the Borderlands.”

License exclusive to Lance Thurner’s Arcadia article “Botanizing the Borderlands.”

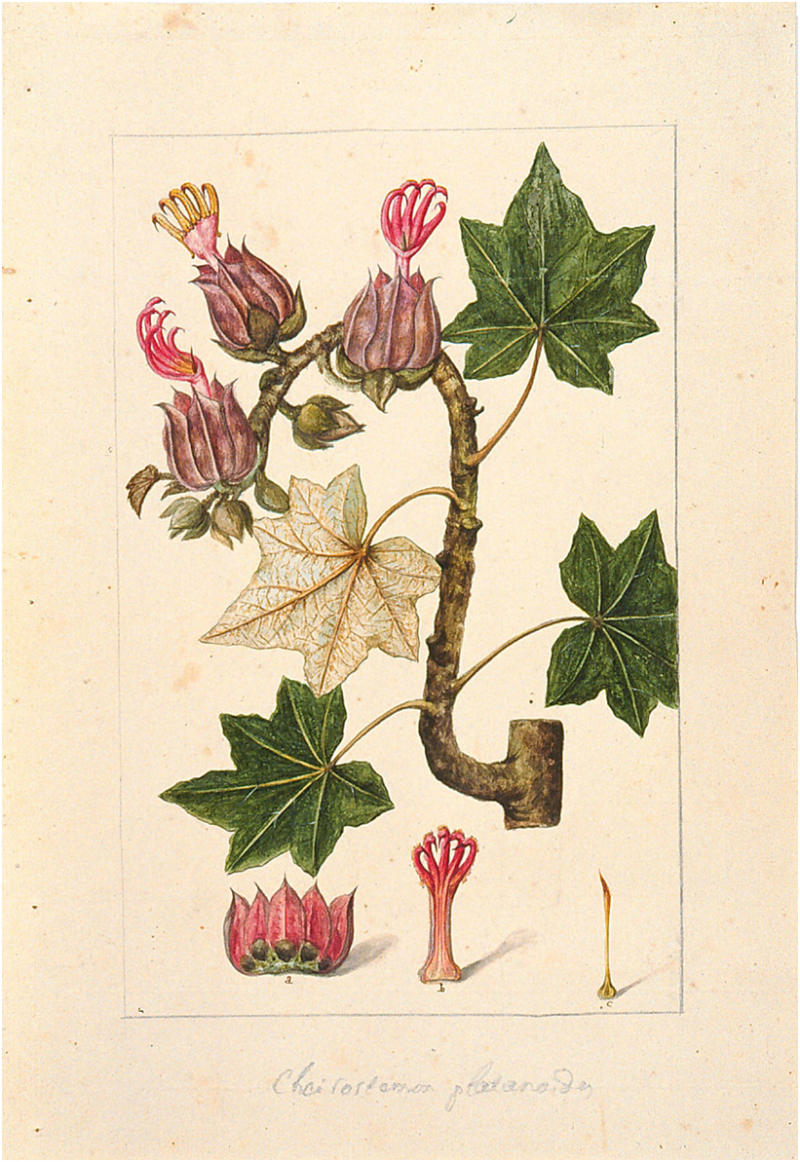

© Torner Collection of Sessé and Mociño Biological Illustrations, 6331.0894. Courtesy of the Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation, Carnegie Mellon University, Pittsburgh, Pa.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Sessé and Cervantes, like many, were particularly keen to collect the supposedly innate knowledge Indians had of nature. King Charles III specifically mandated the expedition to New Spain to recover any remaining traces of Aztec medical botany, knowledge that could be translated into a royal monopoly (see Bleichmar 2012). Along with their intellectual peers in Mexico City, they bemoaned that “we now lack so many remedies” because the conquistadors and inquisitors had banished such wisdom. But they held out hope that “there are memories of this Medicine and Botanica among the Indians of the villages quite distant from the Cities, where our doctors never will hear of it” (de León y Gama 1782: 3).

The Botanical Expedition’s mission, and by extension León y Pérez’s, was both to school provincial colonial doctors in “true medicine” coming from the universities of Europe and to recover uncontaminated, authentic Indian medicine from the edges of empire.

León y Pérez was an ideal fieldworker, or so they hoped, one with a bit of that innate Indian capacity to know plants. But enlightenment-style indigeneity received no warm welcome on the frontier. At Santa Rosa, he entered a quagmire of broken peace treaties, murder and genocide, kidnapping and marauding. His superior, commander Ramón de Castro, favored genocide over peacemaking and felt no compulsion to honor truces made with “barbarians.” But it was less the Indian-hating than the syncretic modus vivendi of frontier survival that crushed his scientific mission. Immediately upon arrival, everything went wrong:

The pharmacy is a waste since the inhabitants here [at Santa Rosa] have no respect for true medicine and medical practice. The surgeon and I have had to tolerate much derision, scorn, and infamy from the pueblo because of the efforts of one insolent and cocky curandero to persuade [the people] of our total lack of expertise. The curandero’s disdainful opinion is supported by the natural crudeness of all the residents, resulting in great confusion and harm. The surgeon and I even have to fight for the respect of the Señor Comandante (the fortunate bastard). I am persuaded that around here the people are of the high opinion that the medications of the pharmacy are very harmful because they are unknown. (León y Pérez 3 February 1793)

Between Spaniards and the many native peoples fighting for control of the region, violence was omnipresent. However, for all involved, survival required careful adaptation and blending of material practices—from horsemanship to healing herbs. Missionaries and frontier militias alike selectively adopted native modes of survival and warfare in such hostile environments. Although Spanish colonialism writ large relied on clear distinctions between Christian and other, the borderlands would not brook such comforts to the conquerors’ souls. The darlings of León y Pérez’s curriculum at the Botanical Garden—true science and pure Indian wisdom—never traveled far from the capital.

ONLY TO BE USED IN “BOTANIZING THE BORDERLAND” BY LANCE THURNER.

ONLY TO BE USED IN “BOTANIZING THE BORDERLAND” BY LANCE THURNER.

© Ministro de Culture y Deporte. Archivo General de Indias, AGI, MP-Mexico, 416.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Therefore, things did not get any better. The “cocky curandero” kept his monopoly on the esteem of the soldiers and León y Pérez’s own pedantry blinded him to the syncretic medical knowledge that surrounded him. Meanwhile, the prickly “fortunate bastard” commander forced León y Pérez to build his own facilities from adobe bricks and refused the latter’s requests for an armed escort to collect specimens among the hills. León y Pérez had to resort to following behind the troops, attempting to botanize in the wake of their pillage and destruction.

ONLY TO BE USED IN “BOTANIZING THE BORDERLANDS” BY LANCE THURNER

ONLY TO BE USED IN “BOTANIZING THE BORDERLANDS” BY LANCE THURNER

© Ministro de Culture y Deporte. Archivo General de Indias, AGI, MP-Mexico, 418.

Used by permission.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Ignacio de León y Pérez did not rise up in revolt, yet his mission for science was a failure. Shut out from local healing networks and trapped within the fort, he learned nothing about indigenous medical practices. The weeds he scavenged he described with technical precision, but without any of the practical knowledge that the Botanical Expedition and the Botanical Garden were created to attain. His notes molded, his career floundered, and he disappeared from the historical record.

How to cite

Thurner, Lance. “Botanizing in the Borderlands.” Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia (Autumn 2019), no. 33. Rachel Carson Center for Environment and Society. doi.org/10.5282/rcc/8749.

ISSN 2199-3408

Environment & Society Portal, Arcadia

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

2019 Lance Thurner

This refers only to the text and does not include any image rights.

Please click on an image to view its individual rights status.

- Bleichmar, Daniela. Visible Empire: Botanical Expeditions and Visual Culture in the Hispanic Enlightenment. Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2012.

- Canales Santos, Alvaro. Valle y presidio de Santa Rosa, 1590–1821. Múzquiz, Coahuila: Centro de Información de Historia Regional, 2002.

- de León y Pérez, Ignacio. “Carta de Ignacio de León a Martín Sessé comunicando su intencion de solicitar el traslado del Valle de Santa Rosa a la Villa de la Mondova y al la del Saltillo, por razones de salud y seguridad al no pisoner de escolta para sus salidas al campo” (February 3, 1793), V, Box 1, Folder 4, Doc. 2, Real Jardín Botánico.

- de León y Pérez, Ignacio. “Carta de Ignacio de León, correspondient del Jardín Botánico de México, a Martín Sessé solicitando una recomendación para trasladarse del valle de Santa Rosa al no poder herbolizar por falta de escolta.” (March 28, 1793), V, Box 1, Folder 4, Doc. 10, Real Jardín Botánico.

- de León y Pérez, Ignacio. “Carta de Ignacio de León, correspondient del Jardín Botánico de México, a Martín Sessé, donde le cominica que ya tiene escolta para sus trabajos de campo y el resultado de los mismos” (April 30, 1793), V, Box 1, Folder 4, Doc.15, Real Jardín Botánico.

- de León y Gama, Antonio. Instrucción sobre el remedio de las lagartijas nuevamente descubierto para la curación del cancro, y otras enfermedades. Mexico: Felipe de Zúñiga y Ontiveros, 1782: 3.

- Valdés, Manuel Antonio. Gazetas de Mexico: compendio de noticias de Nueva España desde principios del año de 1784. Mexico City: por D. Felipe de Zuñiga y Ontiveros, Calle del Espíritu Santo, 1794: 704–5.