Pollution and Industrialization of the Neva and Viennese Danube in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Rapidly growing cities of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries were full of environmental risks and problems. They were often overcrowded, industrialized, and equipped with quite primitive sanitary technologies. Urban dwellers used to dump their waste into their rivers. During the first decades of the nineteenth century, urban populations started to consider pollution a problem. In this section we describe similarities and differences in the history of water supply, pollution, and waste management in St. Petersburg and Vienna. Both cities faced similar problems, though St. Petersburg used the Neva as a source of drinking water while Vienna started to tap Alpine rivers as sources of drinking water in the 1870s.

Switch between the Neva and Danube perspectives by clicking on the circles below.

The original virtual exhibition includes the option to switch between the cities St. Petersburg and Vienna within the individual chapters.

Pollution and industrialization of the Neva in St. Petersburg

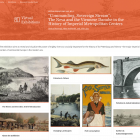

A policeman warns a drowning person that he shouldn’t drink the water—as if this were a greater danger than drowning. Caricature from the journal Satirikon, 1908. Illustration by Re Mi.

A policeman warns a drowning person that he shouldn’t drink the water—as if this were a greater danger than drowning. Caricature from the journal Satirikon, 1908. Illustration by Re Mi.

Courtesy of the State Museum of the History of St Petersburg

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

The water of the Neva is naturally of excellent quality and the people of St. Petersburg were accustomed to enjoying pure and fresh drinking water from the city’s beginnings. Moreover the river has very strong currents and it was therefore able to clean all sorts of waste for some time. But the growing city eventually became a problem too great even for such a large body of water. This was even more true for the smaller branches and canals.

The network of rivers and canals was considered to be a perfect natural sewage system by the dwellers of St. Petersburg. All the city’s waste, including the dwellers’ excrement, was collected in sinkholes and a significant part of it was ultimately discharged into the rivers and canals due to a quite primitive system of waste management. The city police struggled against this habit tirelessly but unsuccessfully. Several times in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the city administration cleaned the small rivers and canals, but still the water quality there was considered rather poor in comparison to the Neva. The water of the main river channel in the city, on the contrary, had a superb reputation throughout the entire eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century. Even the imperial residence, the Winter Palace, to say nothing about ordinary citizens, was supplied with water directly from the Neva without any purification during this period. A legend (which is definitely not true) says that Empress Alexandra Fedorovna (the wife of Nikolas II) used to exclusively drink the water of the Neva and allegedly even required this water to be delivered to her in barrels when she was traveling inside and even outside Russia. In general, the Petersburgers used a lot of water due to their habit of frequently visiting public baths, which was normal even for the poorest people.

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

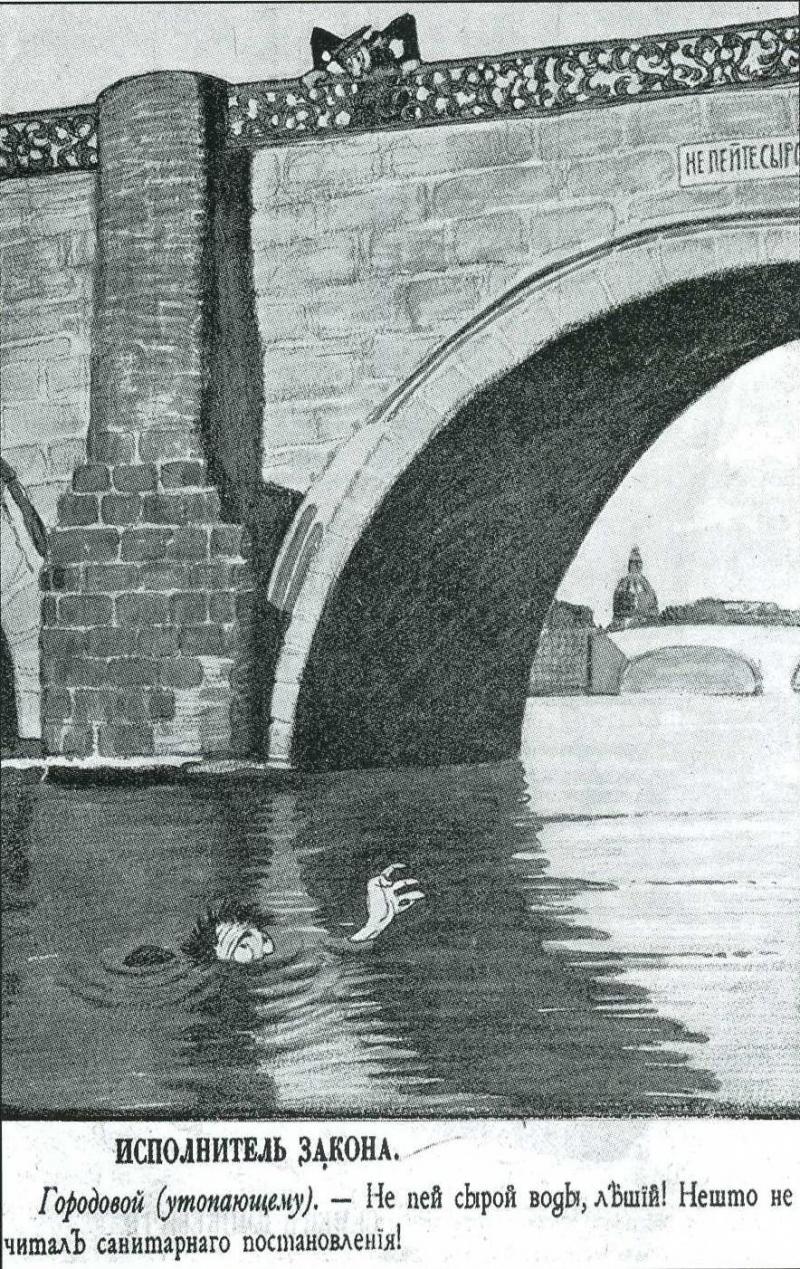

Postcard of the Obvodnyi Canal, early twentieth century

The barges delivered tons of raw materials every day and took finished goods as well as waste on board. The factory produced gas for street lamps using coal and water from the canal. Waste water from the factories contributed to the waste and dirt that accumulated on the banks.

Postcard of the Obvodnyi Canal, early twentieth century.

© The State Museum Reserve “Peterhof,” 2 Razvodnaya Str., Peterhof, Petrodvorets district, St. Petersburg 198516, KП 74035/37. Used by permission.

Postcard of the Obvodnyi Canal, early twentieth century

The sunken barges were significant sources of waste. The banks of the canal looked very much like a huge scrapyard.

Postcard of the Obvodnyi Canal, early twentieth century.

© The State Museum Reserve “Peterhof,” 2 Razvodnaya Str., Peterhof, Petrodvorets district, St. Petersburg 198516, KП 74035/37. Used by permission.

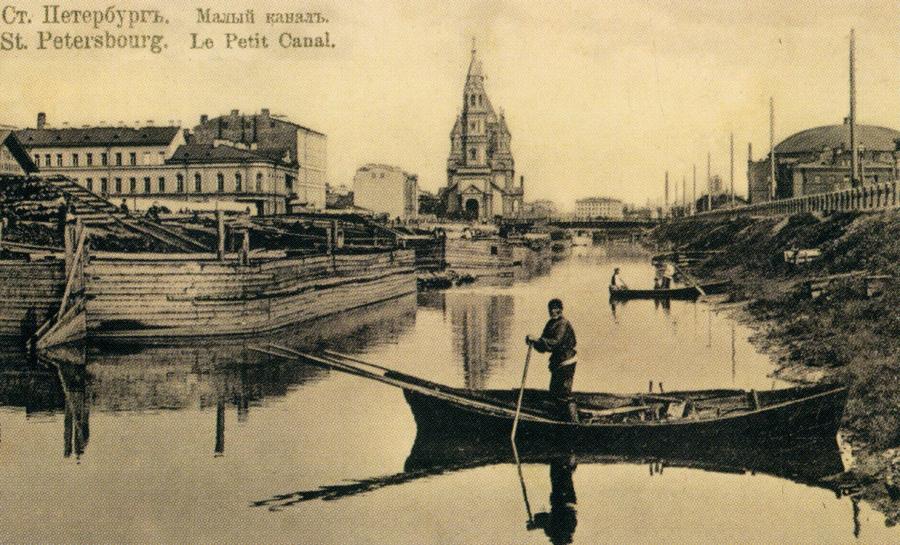

Industrial zone downstream of the Neva, early twentieth century

The shipyards on the banks of the Neva such as the Baltic wharf polluted both air and water. Big vessels drained the used fuel from the steam engines into the water and were among the biggest environmental problems of the city.

Industrial zone downstream of the Neva, early twentieth century. Unknown photographer, n.d.

Courtesy of the State Museum of the History of St Petersburg. Public domain.

The rivers also became an important part of industrial infrastructure. Industrialization in the modern sense of the word started in St. Petersburg in the late eighteenth century. Since the early period of the city’s history, the downstream stretch of the Neva had been used for storage, piers, and wharfs, including the Admiralty shipyard. It is therefore very understandable that this area became one of the city’s earliest industrial zones. Later, plants and factories also occupied the Neva’s banks upstream from the city center, as well as the northern coast of the Big Nevka and the banks of the Obvodnyi Canal. The Neva’s water was used in all stages of the technological process and the waste produced, together with the dirty water, was ultimately dropped into the rivers and canals.

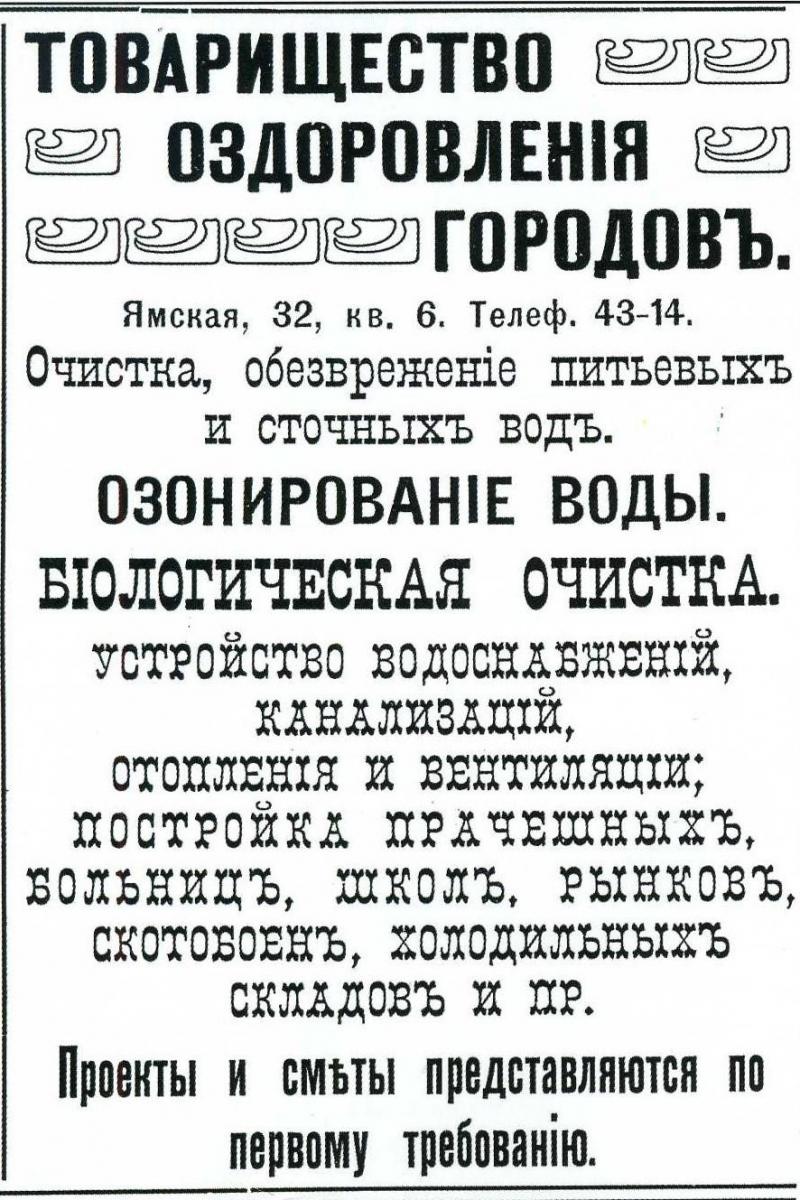

Billboard of the Company for the Health of the Cities, early twentieth century. The company “For the Healthy Cities” was involved in the construction and management of water cleaning and sewage systems. It is worth noting the proposal to erect buildings that required special water treatment technologies: laundries, hospitals, schools, markets, butcheries, ice storage, etc. Unknown illustrator.

Billboard of the Company for the Health of the Cities, early twentieth century. The company “For the Healthy Cities” was involved in the construction and management of water cleaning and sewage systems. It is worth noting the proposal to erect buildings that required special water treatment technologies: laundries, hospitals, schools, markets, butcheries, ice storage, etc. Unknown illustrator.

Courtesy of the State Museum of the History of St Petersburg.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Public Domain Mark 1.0 License.

As a result, as early as the 1830s even the Neva—to say nothing about the smaller rivers and canals—was rather dirty, much worse than its reputation. In 1831 cholera came to St. Petersburg for the first time and some residents accused Polish rebels of poisoning the water of the Neva as the river itself could absolutely not be dangerous in their eyes. But in reality the water became more and more dangerous, and cholera became one of the capital’s major problems until the twentieth century.

The purification of the water in the city became one of the most discussed issues in the journals and newspapers. Public concern about the pollution of the city in general and of the water in particular was very visible. Sanitary technologies were demanded and became the basis for a specific branch of business. A public water supply system was introduced in the 1860s, but it was only in the 1870s that the first water filtration system appeared. It was quite primitive and the companies providing additional water purification found a large market in St. Petersburg in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

The problem of waste water was even harder. The first plans for a more-or-less modern sewage system were drawn up by the engineer Griboyedov in 1912, but it was not completed because of the First World War and the Revolution. A sewage system was not constructed until the Soviet era, although the problem of waste water in St. Petersburg continues to this day.

Pollution and industrialization of the Danube in Vienna

As in many large cities, industrialization in Vienna was also closely linked to population growth and urbanization. These events changed the role of the Viennese Danube as an urban transport route and as a sewage carrier, causing pollution in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

One of the major driving forces behind the Danube’s channelization was the need to support new means of river transport. The fixation of the main river canal was the focus of river channelization in Lower and Upper Austria. In Vienna, accommodating the needs of navigation was combined with building a flood protection system as early as the 1870s.

In 1830 the first steamship set off downstream to Budapest. This journey marks the beginning of a new river transport technology on the Austrian and Viennese Danube. In contrast to the common wooden ships, the larger steamships needed deeper channels and could not navigate well around narrow bends; they were also more prone to damage in the unregulated Danube system with its many shallows. In particular, the Donaukanal (Danube Canal) was inadequate for steamship navigation, which was thus transferred to the main arm of the Danube. Freight was unloaded in a harbor far away from the urban center and had to be brought there with carts and later by local railways.

For centuries, transport on the Danube supplied Vienna, as the capital of a large empire, with fuel and wood for construction. After the 1850s, coal gained importance in Vienna as a new energy source. Although food and other goods remained important ship freight throughout the nineteenth century, the shift to coal changed the river’s role. No natural waterway connected Vienna with the main coal mines in the northern parts of the empire (Moravia, Silesia). Several projects to build artificial canals were developed, although building new railway lines ultimately seemed to offer better opportunities.

Interestingly, the first railway line built in Vienna in 1837, the Northern Railway, was also closely connected to the Danube. The main station was situated on an island in the Danube and the railway bridge that crossed the northern arm of the Danube was regularly destroyed by floods. In such cases, rail connections were interrupted until maintenance work was completed.

The original virtual exhibition includes an interactive gallery of images. View the images on the following pages.

Shiffsverkehr auf der Donau

After the completion of the Great Danube Regulation in 1875, the main navigation route moved to the newly built main arm of the Danube. The Rotunda, a landmark built for Vienna’s 1873 World Exposition, can be seen at in the background.

Wilhelm Bernatzik, Schiffsverkehr auf der Donau [Ship traffic on the Danube], before 1886. Watercolor.

© Österreichische Nationalbibliothek/Wien, pk 1131,98. Used by permission.

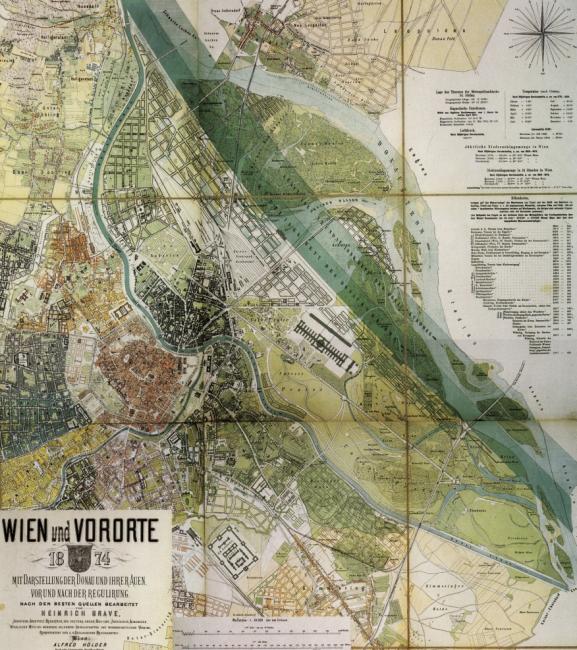

Vienna and suburbs

The Danube floodplains became an important land resource in the fast growing town. In this map from 1874, the new Danube River and the envisaged expansion of the city in the former Danube floodplains is seen.

Vienna and suburbs. Map by Heinrich Grave, 1874.

© Wiener Stadt- und Landesarchiv, Pläne und Karten: Sammelbestand, P1: 756G. Used by permission.

While the river’s role in transporting the food and goods required for everyday life declined throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, its function as a sewage disposal site increased. In 1800, Vienna had about 200,000 inhabitants; by the mid-nineteenth century the number had more than doubled. In the 1870s the milestone of one million was passed and, at the beginning of the twentieth century, more than two million people lived within what are now the town limits. The growing population increased the organic input to the Danube and its tributaries. Potential nitrogen input from private households into the Donaukanal rose by a factor of seven between 1830 and 1910. This was accompanied by an as yet unreconstructed amount of industrial organic and inorganic waste.

By 1830 more than 80 percent of the Viennese households within the contemporary tax boundary were connected to sewers. The small brooks seemed to be an optimal solution for removing excrement and waste. They were therefore integrated into the urban sewage infrastructure right from the beginning. The inefficiency of this sewage system resulted in serious water pollution, especially in the small tributaries with their low water discharge. This triggered several epidemics. The first cholera outbreak in Vienna occurred in 1830–31. The bad sanitary situation prompted the development of a central waterborne sewage system. It was completed at the turn of the nineteenth to the twentieth century by opening one central outlet to the Donaukanal. An important prerequisite was that the city could be supplied with sufficient water from Alpine sources south of Vienna. The “Erste Wiener Hochquellwasserleitung,” Vienna’s first Alpine water supply system, was opened in 1873.

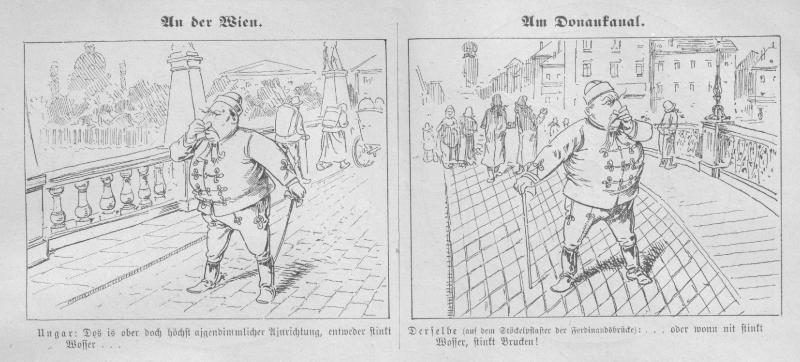

The stench from the polluted rivers was the subject of various satirical cartoons. Caricature in Wiener Luft, Supplement to Figaro 37, 15 September 1888. Unknown illustrator.

The stench from the polluted rivers was the subject of various satirical cartoons. Caricature in Wiener Luft, Supplement to Figaro 37, 15 September 1888. Unknown illustrator.

© Österreichische Nationalbibliothek/Wien, ANNO-Austrian News Papers Online.

This work is used by permission of the copyright holder.

Although the discharge of the Donaukanal was much higher than that of the small tributaries, water quality was often assumed to be insufficient, in particular for keeping fish fresh in wooden barrels to be sold at the central fish market. Written sources from the 1890s document the debates between fish traders arguing for sufficient water quality in the Donaukanal and urban dwellers complaining about the bad taste of fish. The situation improved after the new central fish market was built in 1904.

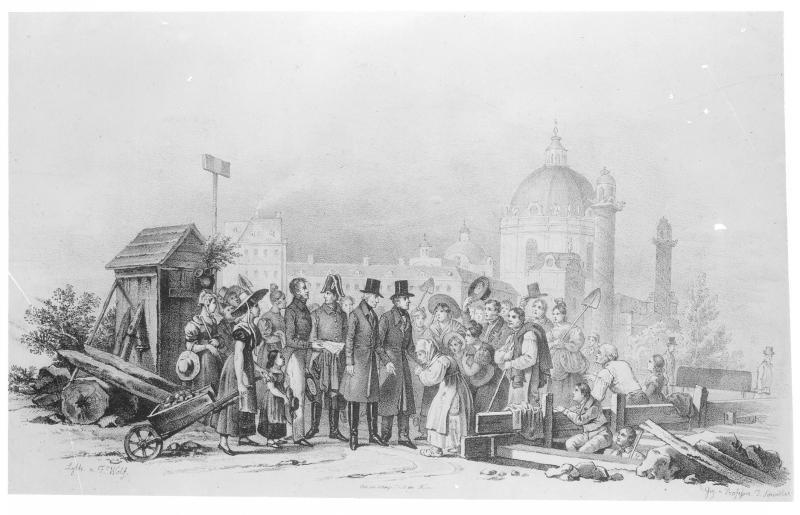

Francis II, Holy-Roman Emperor

The Wienfluss was the largest tributary of the Viennese Danube and suffered from severe pollution. Sewage canals were built after the first cholera epidemic in 1830 and 1831. In the middle in the foreground, Emperor Franz II is shown visiting the construction site.

Franz Wolf and Johann Josef Schindler, Franz II., römisch-deutscher Kaiser [Francis II, Holy-Roman Emperor], 1831.

© Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Wien, NB 504.355–C. Used by permission.

Concreting of a vaulted ring below the Elizabeth Bridge

The Wienfluss was vaulted at the end of the nineteenth century. In the 1890s it was the main tributary of the Donaukanal.

Photograph by R. Lechner, 11 October 1898.

CC0. Courtesy of Wien Museum.

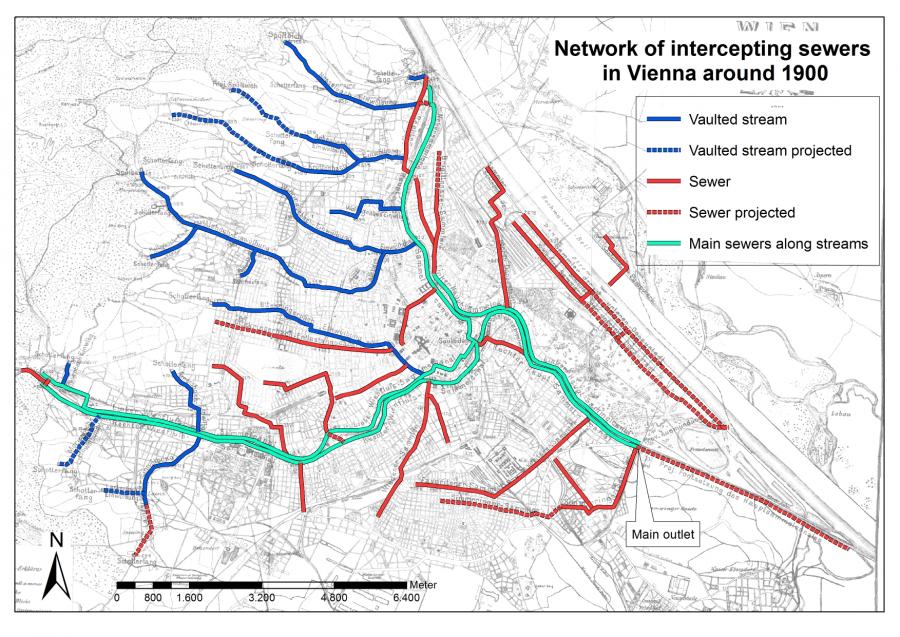

Die Entwässerung von Wien

Around 1900, Vienna had an elaborate sewage system into which most of the small tributaries were integrated.

Map by Gertrud Haidvogl based on “Die Entwässerung von Wien” by P. Kortz. In Weyl, T., ed. Die Assanierung von Wien, edited by T. Weyl. Leipzig: Engelmann, 1902. Plate 3.

This work is licensed under a CC-BY-NC-SA 4.0 International License.

Switch between the Neva and Danube perspectives by clicking on the circles above.