“Room eno’ for all”: Promotion of Settlement in Iowa and Nebraska

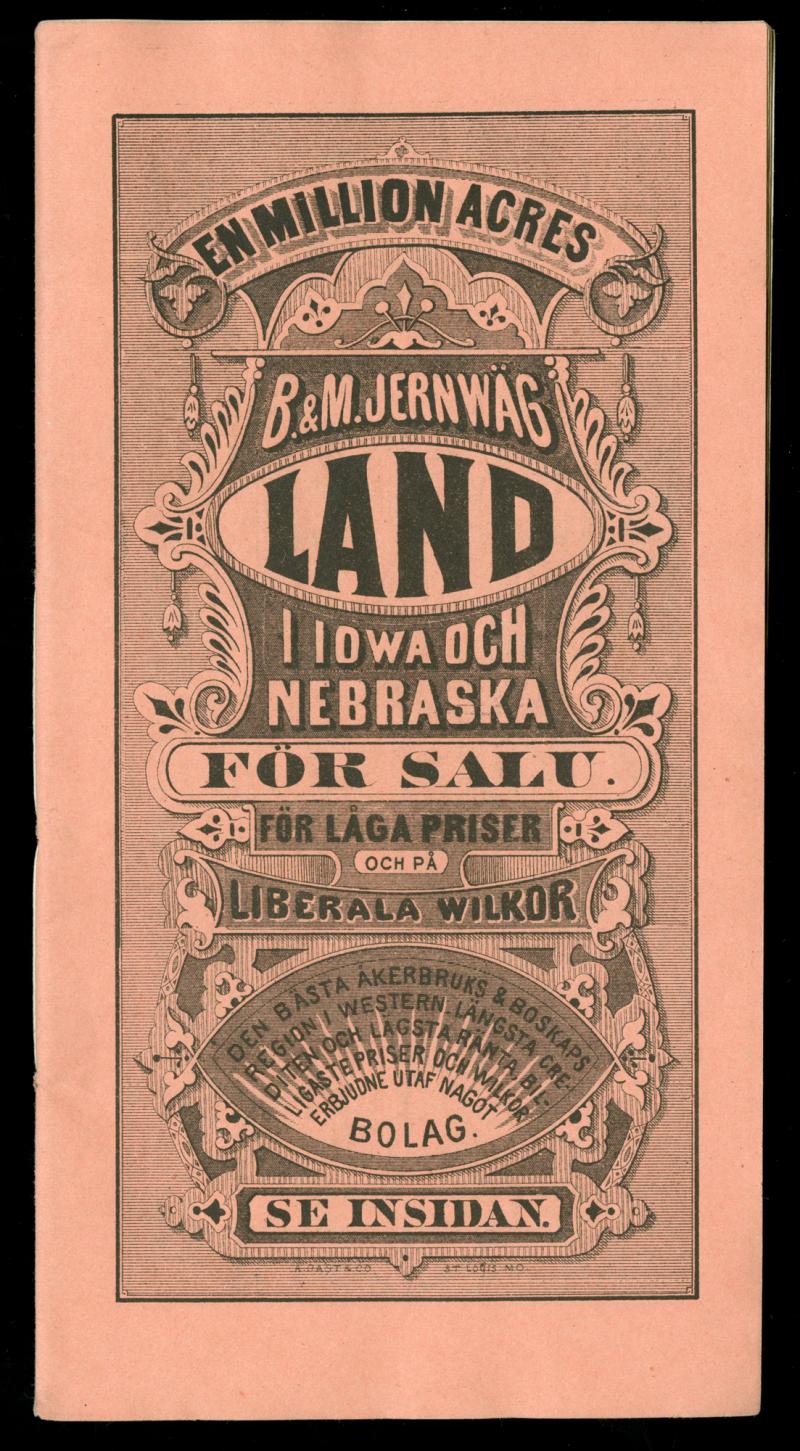

CB&Q brochure cover: “En million acres för salu” brochure (in Swedish), c. 1879.

CB&Q brochure cover: “En million acres för salu” brochure (in Swedish), c. 1879.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q +769.8 #66-1, Brochures.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

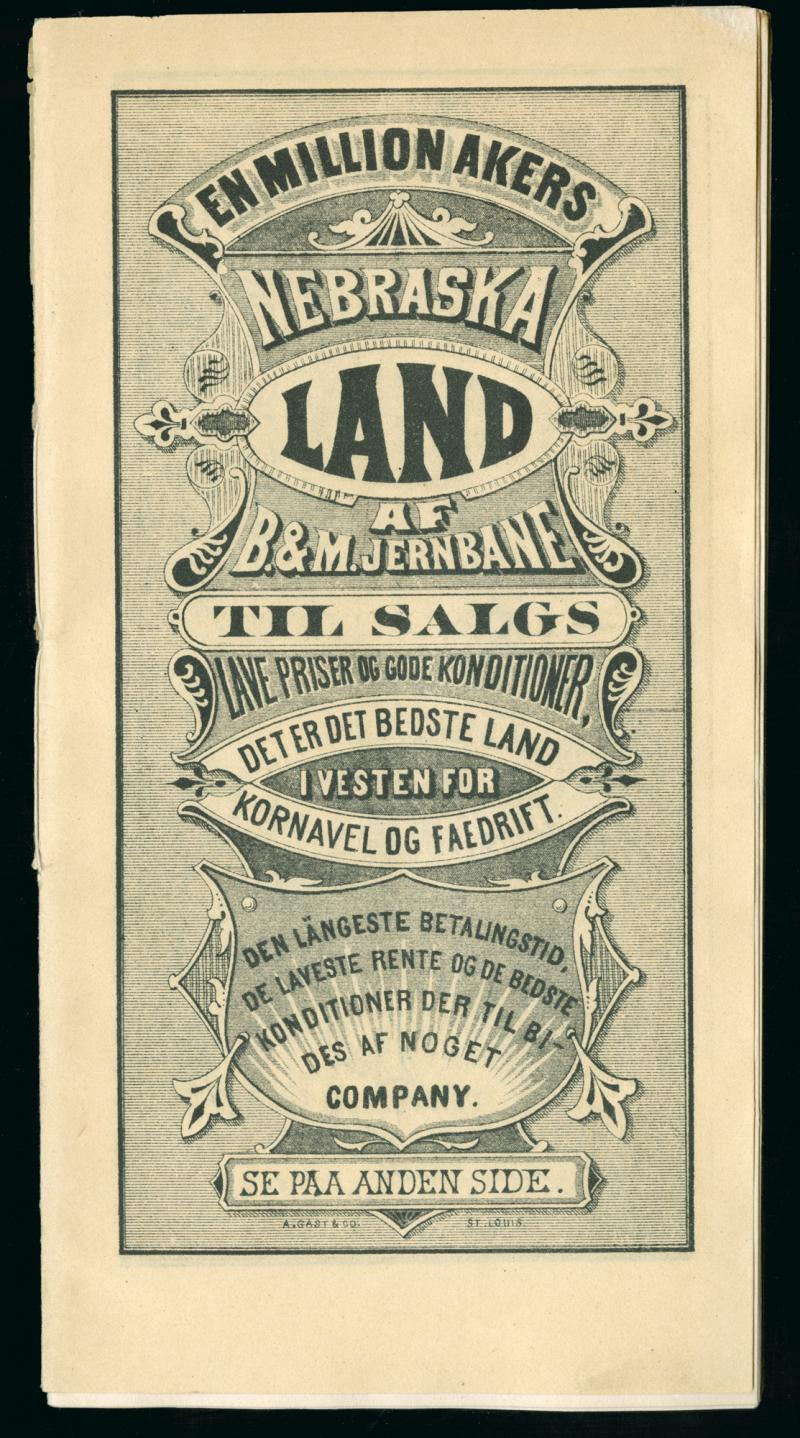

CB&Q brochure cover: “En million akers til salgs” brochure (in Danish), c. 1879.

CB&Q brochure cover: “En million akers til salgs” brochure (in Danish), c. 1879.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q +769.8 #66c, Brochures.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

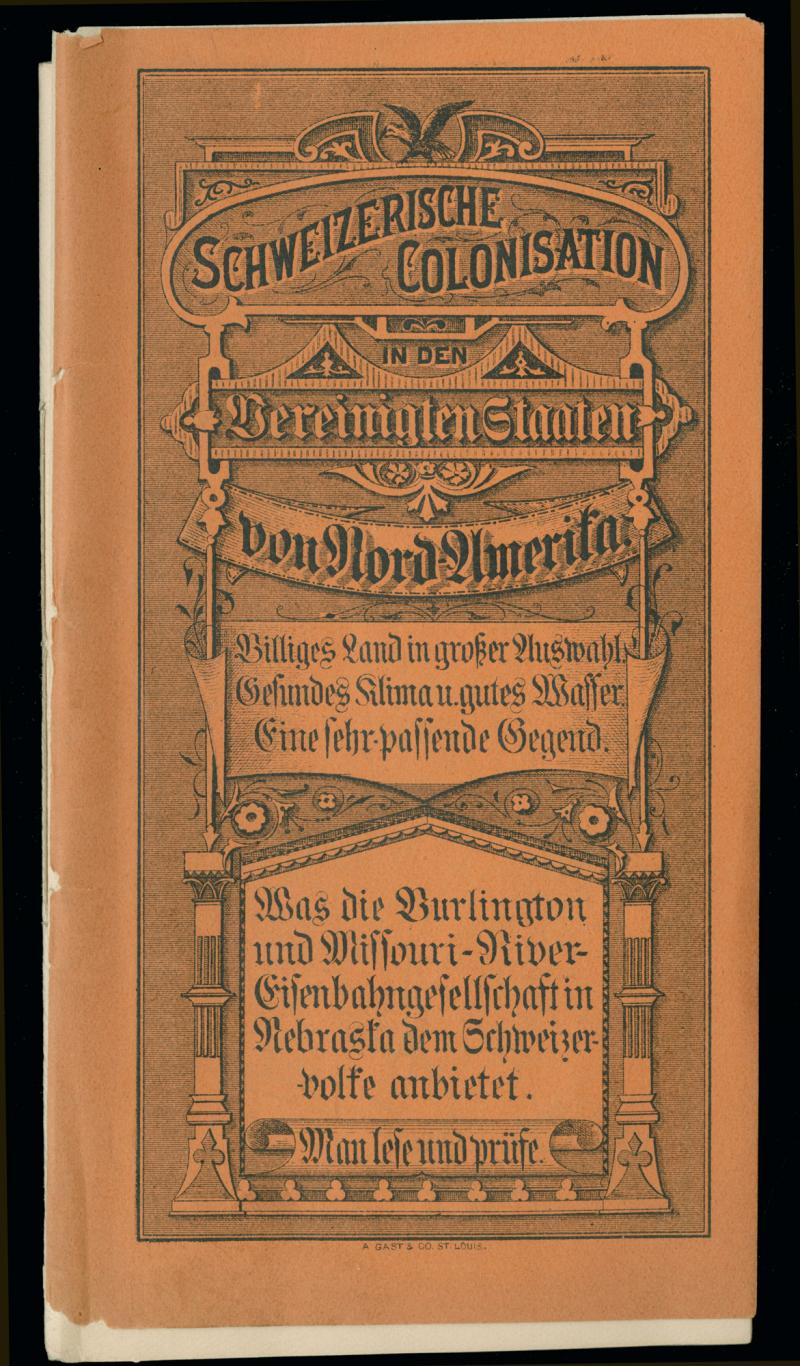

CB&Q brochure cover: “Schweizerische Colonisation” brochure (in German), c. 1879.

CB&Q brochure cover: “Schweizerische Colonisation” brochure (in German), c. 1879.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q Brochures.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

CB&Q brochure cover: “Jeden milion akrů na prodej” brochure (in Czech), c. 1879.

CB&Q brochure cover: “Jeden milion akrů na prodej” brochure (in Czech), c. 1879.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q +769.8 #66-2.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

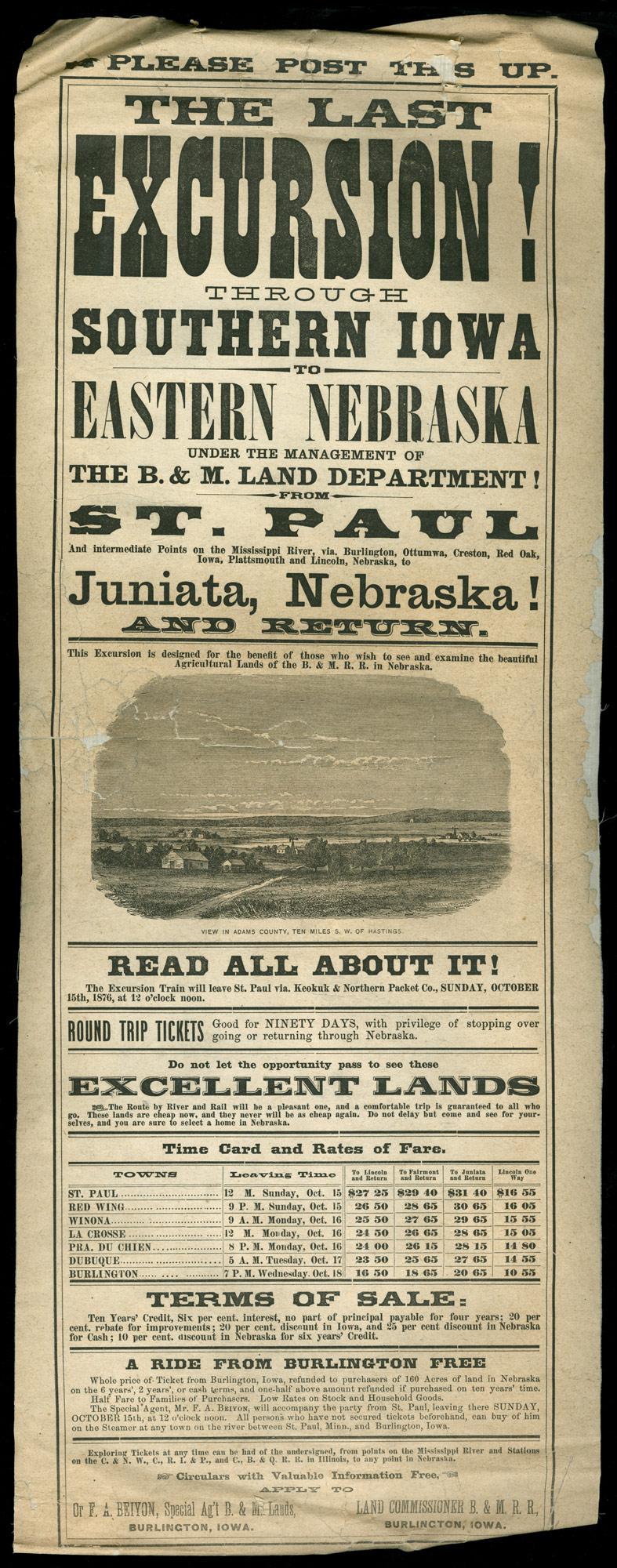

An 1876 CB&Q poster: “The Last Excursion! Through Southern Iowa.”

An 1876 CB&Q poster: “The Last Excursion! Through Southern Iowa.”

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Poster CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

As the Burlington prepared to sell its Iowa grant lands they laid the foundations for what Overton said “would ultimately become their most important work, the advertising and sale of its lands.” Although some of the Burlington’s Iowa lands sold in the 1860s, most of the company’s lands in Iowa and Nebraska were sold between 1870 and 1880. This was due to an aggressive sales campaign that began in 1870 as hundreds of thousands of advertising pamphlets printed in English, German, French, Welsh, Bohemian, Norwegian, Swedish, and Czech were distributed in the United States, Canada, and Europe. More than 250 land agents sought settlers from east of the Mississippi and north of the Ohio rivers. Land offices were opened in England, Scotland, Germany, and Sweden.

In an effort to get prospective buyers to visit the lands, the Burlington offered exploring tickets to Iowa and Nebraska. At first the tickets were full fare, but fare for the portion of the trip in the state where land was purchased could be credited against the purchase price. When land sales policies were liberalized in 1873, the company offered discounted fares for exploring tickets. Those buying land in Iowa could receive free fare from Chicago, and those buying land in Nebraska received half-price fare through Illinois and Iowa, and free fare west of the Missouri River. Discounts were also offered for family members and for freight.

The CB&Q established two emigrant homes, one in Burlington and the other in Lincoln, where prospective buyers and their families—and even colony groups—could stay free of charge while looking for land.

Feeling part of a community was an important factor in whether or not settlers stayed on their land. Recognizing this, the Burlington encouraged immigrants to form colonies that could travel together to the land grant regions. Many of these groups came under the leadership of a pastor. The company even offered land to congregations to help establish churches. These efforts not only helped build durable communities, they also fostered good will for the Burlington brand. Furthermore, the company did not tolerate religious discrimination. As Colonel John W. Ames put it, “there is room eno’ for all—the B. & M. do not propose to favor one sect more than the rest.”

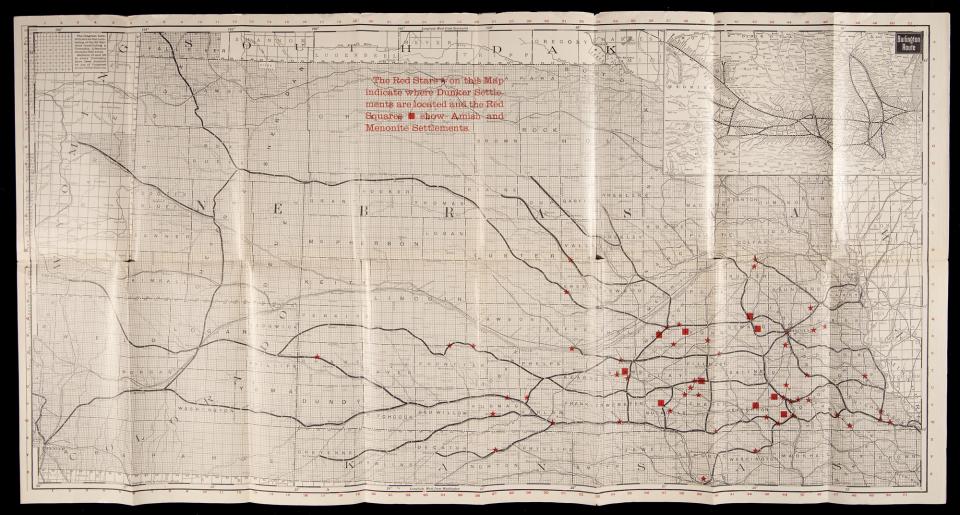

CB&Q map showing Dunker, Amish, and Mennonite settlements in Nebraska, c. 1900.

CB&Q map showing Dunker, Amish, and Mennonite settlements in Nebraska, c. 1900.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Brochures.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This remarkable map shows Dunker, Amish, and Mennonite settlements in Nebraska. The other side contains typical promotional information aimed at attracting Dunkers to settle on Burlington lands. The Dunkers trace their history to 1708 in Schwarzenau, Germany, where they called themselves Neue Täufer (New Baptists) in order to differentiate their group from older Anabaptist groups, such as the Mennonites and the Amish. They were also called Brethren. They emigrated to America in the early eighteenth century, settling mainly in Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Maryland, Virginia, and North and South Carolina. They were called “Dunker” by outside groups, not always kindly, in reference to their practice of adult immersion baptism.

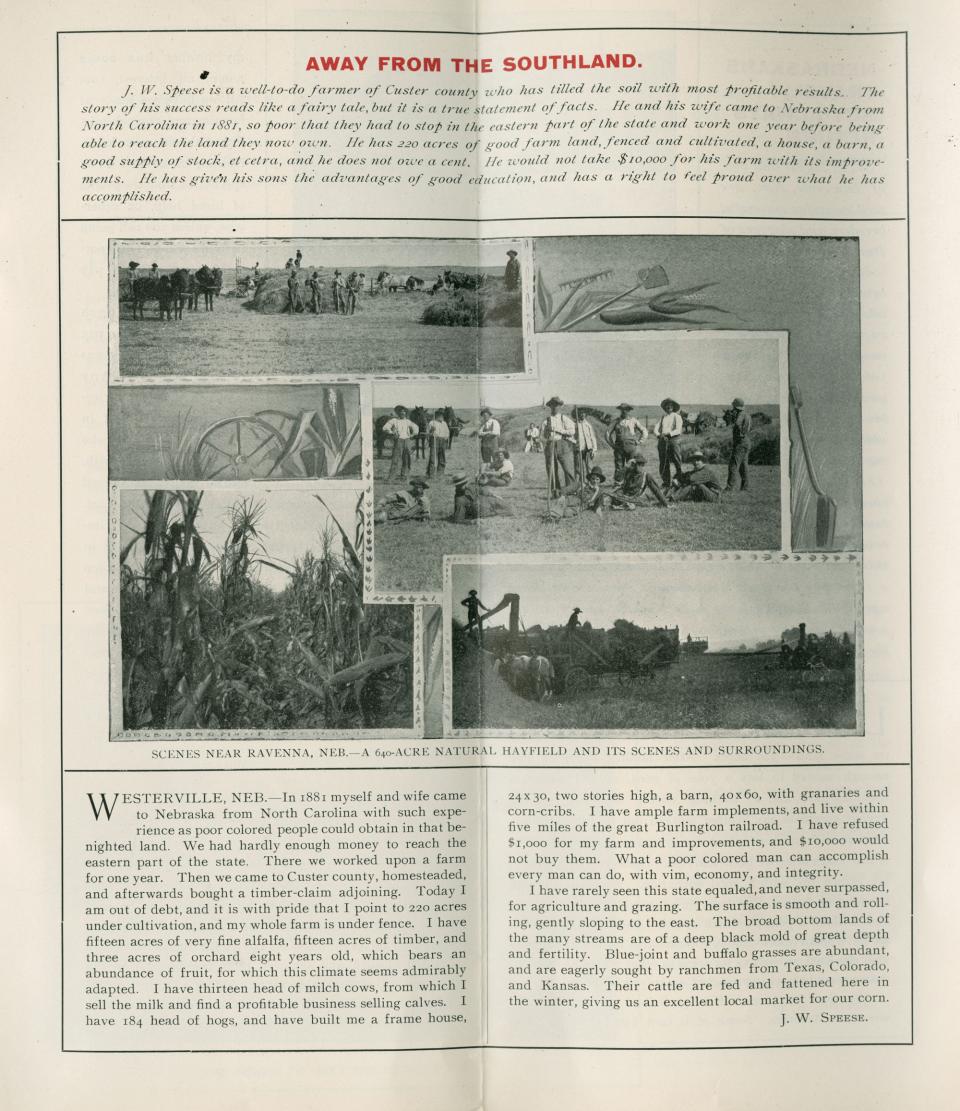

CB&Q brochure “Away from the Southland,” 1899.

CB&Q brochure “Away from the Southland,” 1899.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Brochure.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The Burlington’s openness policy also extended to African American settlers. This is one of several letters from successful settlers to Nebraska printed in a brochure titled “The Truth About Nebraska.” The author/subject of this one is an African American couple who migrated to Nebraska in 1881 “from North Carolina with such experience as poor colored people could obtain in that benighted land.” As the framing header states, the story “reads like a fairy tale, but is a true statement of facts.” Presumably, this success story was aimed at attracting other African Americans who, like J. W. Speese, sought to escape the limitations imposed in other sections of the country to a land where “even” a black man could become a successful farmer and provide “his sons the advantage of good education.”

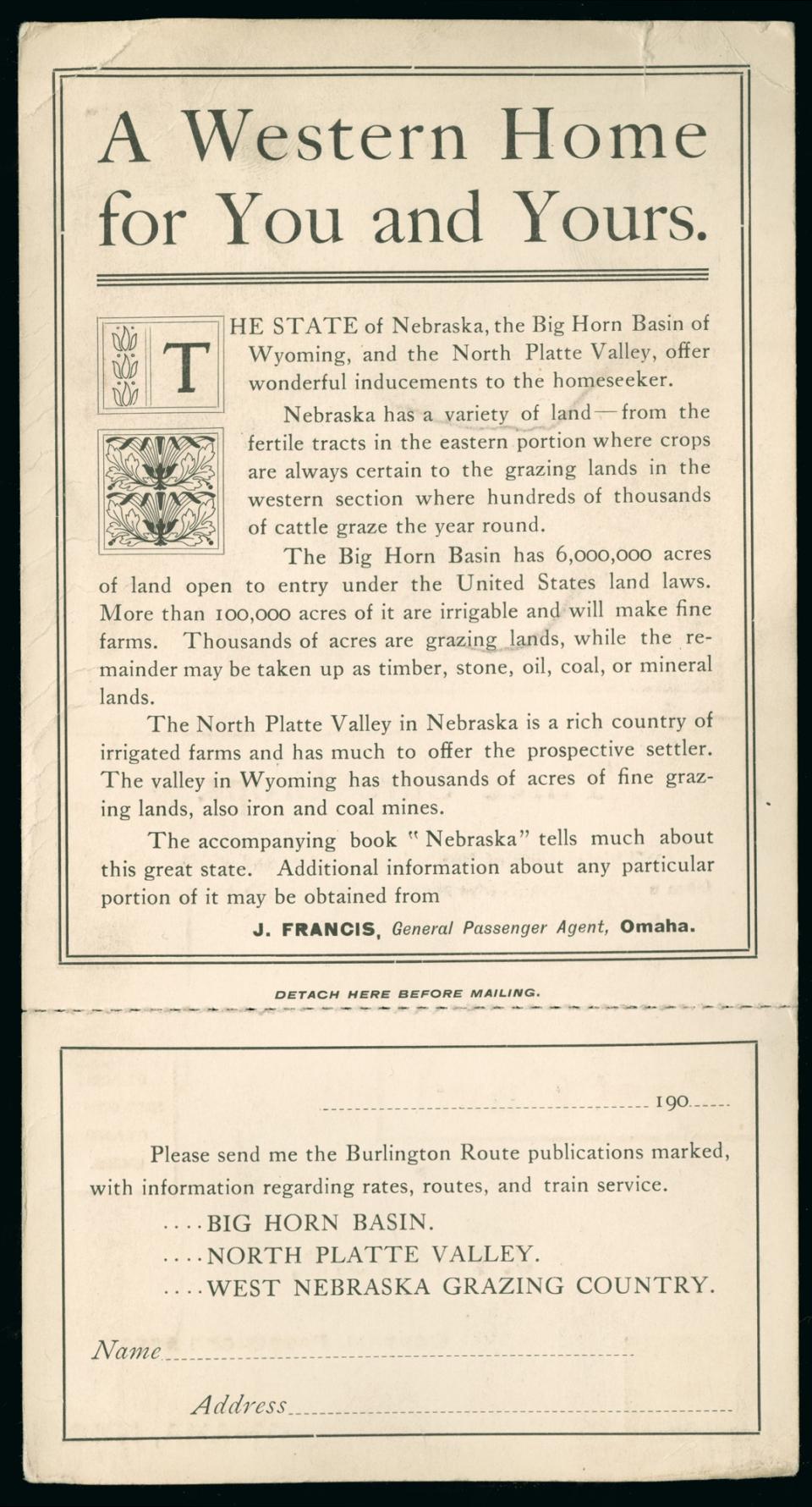

Advertisement with postcard: “A Western Home for You and Yours,” 1900.

Advertisement with postcard: “A Western Home for You and Yours,” 1900.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Advertisement with postcard: “Three Sure Crops,” 1900.

Advertisement with postcard: “Three Sure Crops,” 1900.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q 769.8.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This postcard illustrates the Burlington’s advertising savvy and their emphasis on attracting families in their effort to establish stable communities and a steady, growing freight and passenger business.

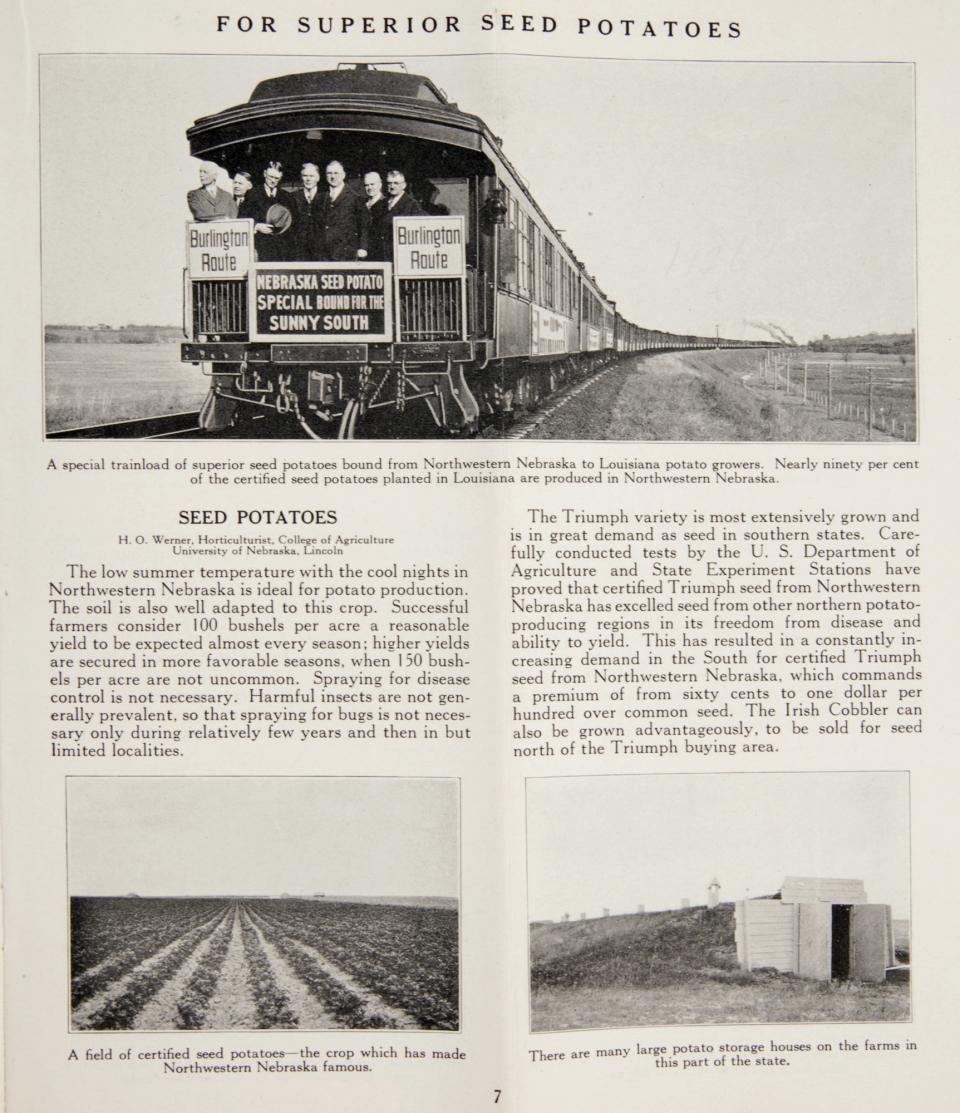

Booster literature was a genre produced by state governments, land companies, newspaper editors, and railroads that was intended to promote particular places or regions to encourage economic development through investment, settlement, and creation of industries. Burlington lands booster literature—as all booster literature—sometimes made exaggerated claims, but the company made serious efforts to make their optimistic predictions come true. In addition to cooperating with state university and federal experiment stations, the company promoted and printed research from agriculturalists and provided seed to farmers. In addition to potatoes, the Burlington helped promote alfalfa, corn, cotton, grains, grapes, hops, sorghum, sugar beets, and tomatoes. They collected crop samples to display at agricultural fairs around the country and in Europe. The Omaha Daily Herald reported that Nebraska crops, “together with an elk head and horn” were popular exhibits in Derby and at the opening of Sefton Park, in Liverpool by Prince Arthur in 1872.

Advertisement for seed potato train in “Northwestern Nebraska,” 1926.

Advertisement for seed potato train in “Northwestern Nebraska,” 1926.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q Brochure, Misc. Bx. #4.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

- Schwantes, Carlos A. Going Places: Transportation Redefines the Twentieth-Century West. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003.