Scenic Route Guides: “Something worth seeing every hour of the journey”

While some passenger guides focused on the destination, others emphasized the journey. By 1906, the Burlington had begun producing guides for select routes that featured scenic and historic points of interest. The earliest of three examples found in the CB&Q collection is a series of guides for the Mississippi River Scenic Route from 1906 to 1937. These seem to have been the prototype for the two guides for western routes produced in 1945. All of the guides featured here are a place-by-place guide of the route, setting present places in their historic contexts. They situate the Burlington in the history of western expansion and at the pinnacle of the progress of transportation. The two western guides feature a progression from Indian Trails and Wagon Wheels to Stainless Steel Rails, from the romantic to the streamlined and modern.

The guides shaped the travelers’ experience, identified what was worth seeing along the route, described it, and interpreted its significance.

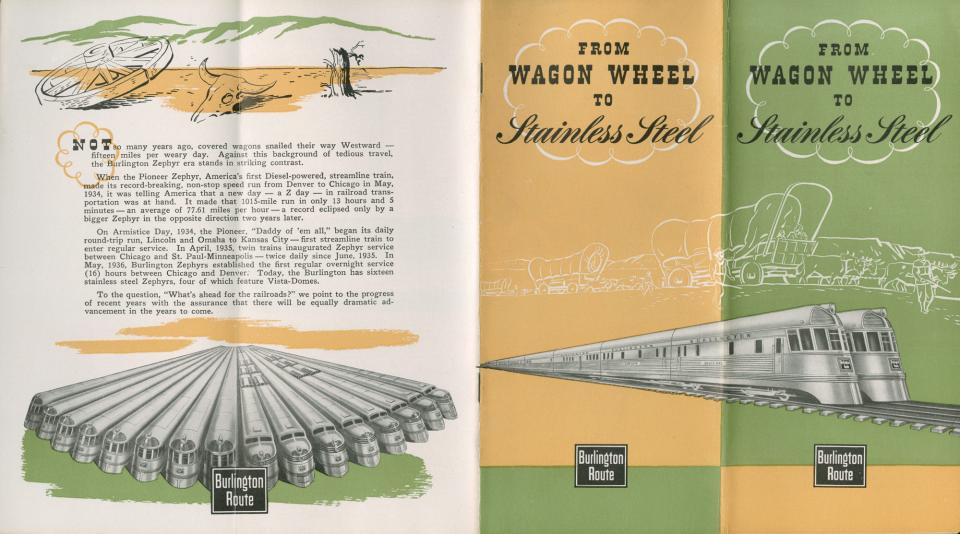

CB&Q brochure: From Wagon Wheel to Stainless Steel, 1945.

CB&Q brochure: From Wagon Wheel to Stainless Steel, 1945.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This brochure has a larger scope than the other two examples from the CB&Q collection. Indeed, it contains part of the Mississippi River Scenic Line up to La Crosse, and all of the Kansas City-Omaha-Lincoln line. The cover juxtaposes the past (wagon trains headed west) with the future (shiny new Zephyrs), while the back cover shows a fleet of Zephyrs below a broken wagon wheel and the bleached skull of an ox in the desert. The text begins: “Not so many years ago, covered wagons snailed their way Westward—fifteen miles per weary day.” This is contrasted with the Zephyrs which could make the run from Chicago to Denver in one day, averaging more than 77 miles per hour, with assurances of “equally dramatic advancement in the years to come.”

CB&Q brochure, Course of Empire: From Wagon Wheel to Stainless Steel, 1945.

CB&Q brochure, Course of Empire: From Wagon Wheel to Stainless Steel, 1945.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This is the Burlington’s “Course of Empire” map. While alluding to Manifest Destiny and the American Empire, it could also refer to the company’s railway empire stretching from Chicago westward to Yellowstone National Park, Glacier National Park, and the Pacific Northwest. The map is neatly framed by a shiny new Zephyr diesel engine and the City of Chicago in the east (right) and a wagon train, Buffalo Bill Cody, and the Rocky Mountain range in the west (left). In this busy map, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West of battles, massacres, and colorful personalities meets the more sedate agricultural frontier of Frederick Jackson Turner as waves of plain hardworking people conquered prairie and forest to create productive farms and small towns. The route of Lewis and Clark, Mark Twain’s birthplace, the Mormon Trail, the Pony Express, literary references—“Spoon River, made famous by Edgar Lee Masters in his ‘Spoon River Anthology,’” the geographical center of the United States, and the dividing line between Central and Mountain Time: all are interwoven with the history of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy Railroad.

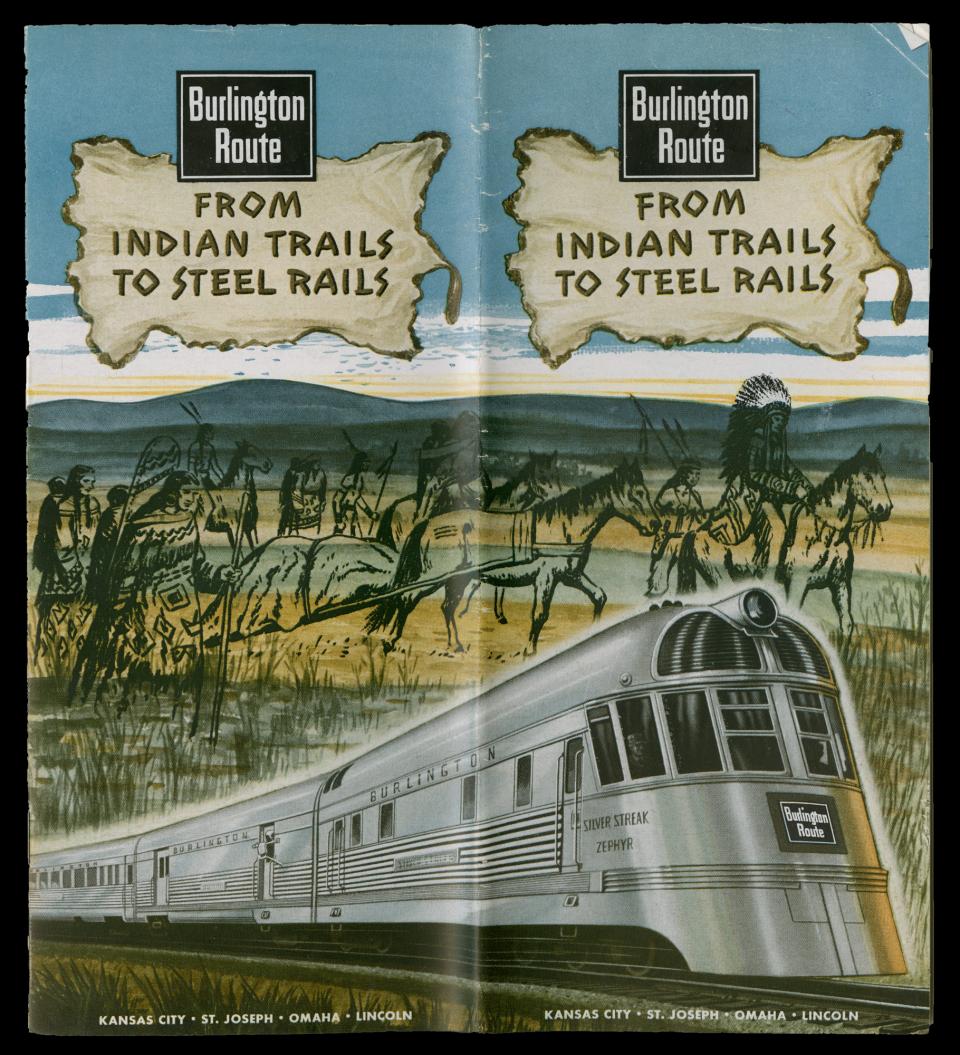

CB&Q Brochure: From Indian Trails to Steel Rails, 1945.

CB&Q Brochure: From Indian Trails to Steel Rails, 1945.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

“From Indian Trails to Steel Rails” map, 1945.

“From Indian Trails to Steel Rails” map, 1945.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

This guide for the Kansas City-St. Joseph-Omaha-Lincoln route seems to have a similar template to the Mississippi River Scenic Line guide. The front cover shows a new Silver Streak Zephyr speeding along the plains, with the ghostly figures of Plains Indians superimposed over the background.

The similarity of this map to the MRSL map is striking. For most of the route from Kansas City, the road hugs the eastern bank of the Missouri River until it crosses westward to Omaha and Lincoln. The map shows the Oregon Trail, the Pony Express route, and the Mormon Trail, but no Indian trail.

Mississippi River Scenic Line brochures, 1906–1937

Probably the earliest and most popular of the Burlington scenic lines was the Mississippi River Scenic Line (MRSL). The company completed its line from Savanna, Illinois, to St. Paul, Minnesota, in 1886, connecting the Twin Cities with Chicago, and passenger lines began running that same year. Although the Burlington route from Chicago to the Twin Cites was twenty-five miles longer than the competing Milwaukee and the North-Western lines, the Mississippi River route had a smoother grade and more spectacular scenery. The company soon called it the Mississippi River Scenic Line and produced a series of brochures designed to enhance the passenger experience. The Burlington’s 1906 guide to the route begins:

By those who know its charm, the Burlington Route between Chicago, St. Paul and Minneapolis has been titled for nearly twenty years ‘The Mississippi Scenic Line.’ The significance is readily understood when one comprehends that for 286 of the 431 miles between Chicago and St. Paul the rails are within sight of the majestic Father of Waters, with a broad, island-dotted expanse on the one hand and bluffs—real, heroic heights—on the other. For many miles the tracks are so close to the river’s edge that a child might easily toss a pebble from the car window to the water.

The lavishly illustrated guide describes the history and geography of the route. Traveling by rail was physically passive, but, as John Stilgoe has noted, watching the scenery go by from a passenger train could be a cinemagraphic experience. The guides were designed to shape the traveler’s experience of the landscapes they passed through. “Not only is there this magnificence of scenery, but every mile is replete with historic and legendary interest.” and on the next page: “Altogether, one may be sure of seeing something worth seeing every hour of the journey, and if he should be so fortunate as to meet an old inhabitant, great will be his interest in the Indian legends and the tales of pioneers.” Wisconsin was an important destination for European immigrants during the nineteenth century, and well into the twentieth century ethnic enclaves were common in rural as well as urban areas. The 1906 guide stated:

A further charm is found in the quaint villages along the river, many of them founded years and years before the advent of the railroad. The pioneers of some were Italians, of others Germans, and of other, Yankees, with the result that one sees here an old-world touch and there New England spruceness. The occupations of many of the villagers are unique, a large number being engaged in the pearl fisheries, an important industry.

The longest section, “About the River and its Environs” provides descriptions of each of the quaint villages along the route, the legend of Maiden rock, a center page photo collage showing scenes like Wolf Den Rock, Palisades, Great Spirit Bluff, and Minnehaha’s grave (neglecting to explain why a fictional character would need a grave), and information pertaining to points of interest, lodging, theaters, dining, in St. Paul and Minneapolis.

The MRSL guides were revised several times. The CB&Q collection contains a collection of historical and other background material used to make the guide, as well as extensive correspondence regarding what should go into the guide. Chambers of commerce saw it as an opportunity to boost their towns.

Burlington officials followed with keen interest the efforts to create an Upper Mississippi Wildlife and Fish Refuge. In 1927, B. W. Wilson, General Agent for the CB&Q passenger department, was invited to attend a meeting in La Crosse, Wisconsin, with their local agent, a couple of representatives of the La Crosse Chamber of Commerce, and the editor of the La Crosse Tribune to discuss the Refuge. On February 26, Wilson wrote to H. F. McLaury, advertising agent for the CB&Q, that “anything you can do to feature this Refuge in connection with the Chicago-Twin Cities services, should be of mutual benefit to our many friends at La Crosse and ourselves.” An advertising counselor from St. Paul sent McLaury an article from the Pioneer Press that predicted the Refuge would be of great interest to tourists. The counselor stated that the Refuge would “become more nearly your exclusive property as a showplace than any other road, apparently there will be no paved highways paralleling your tracks to cut in on the sight-seeing possibilities.”

Letter from IWL Conservation Director Seth E. Gordon to CB&Q Advertising Agent H. F. McLaury, 25 June 1930.

Letter from IWL Conservation Director Seth E. Gordon to CB&Q Advertising Agent H. F. McLaury, 25 June 1930.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3, Mississippi River, Correspondence.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

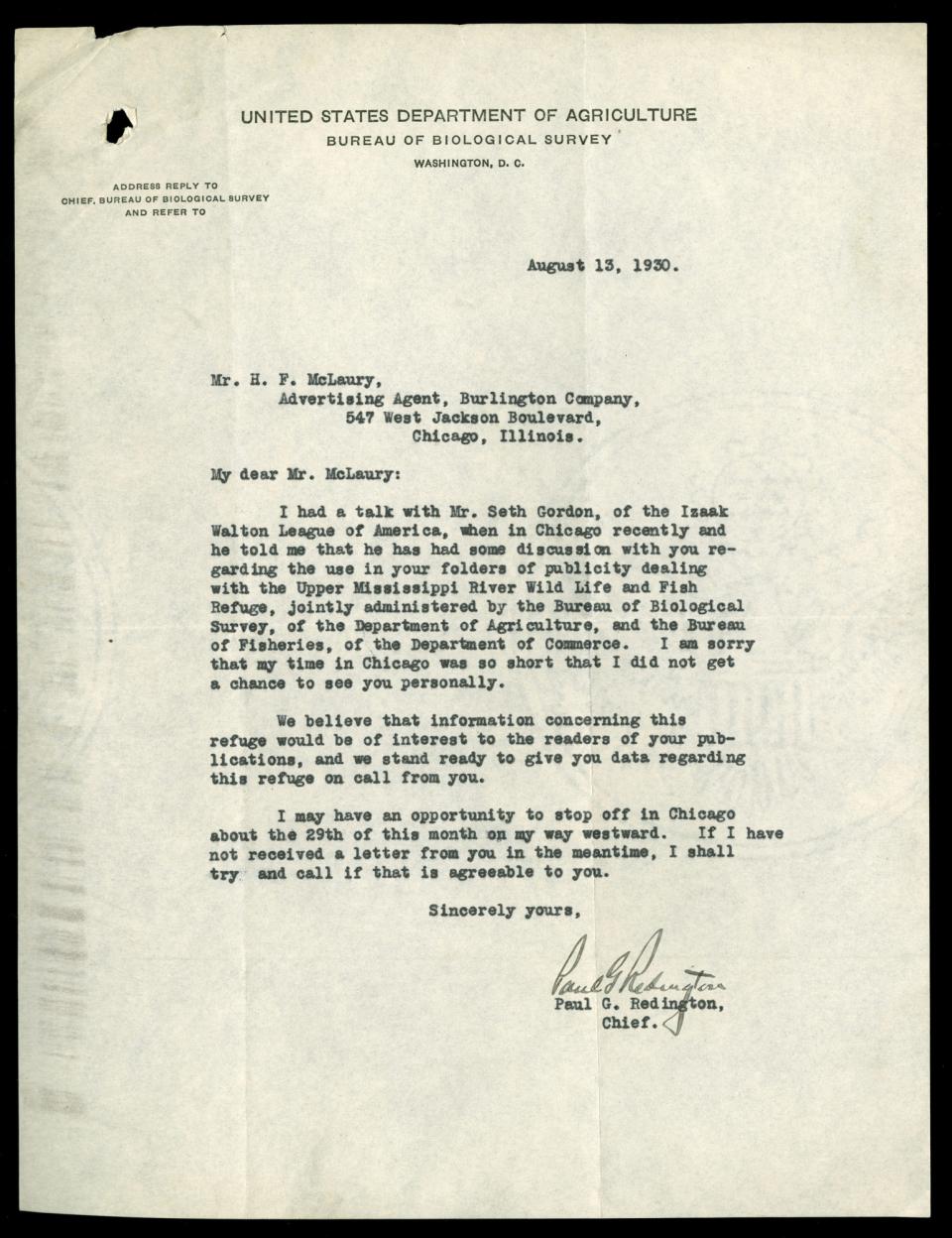

Paul G. Redington to H. F. McLaury, regarding conversation with Seth Gordon (Izaak Walton League), 13 August 1930.

Paul G. Redington to H. F. McLaury, regarding conversation with Seth Gordon (Izaak Walton League), 13 August 1930.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3, Mississippi River, Correspondence.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Creation of the Refuge was a major victory for the Izaak Walton League. Correspondence between H. F. McLaury, Seth Gordon, and Paul Redington shows cooperation between the League, the Biological Survey of the US Department of Agriculture, and the CB&Q to publicize the Refuge. In an earlier letter, Gordon wrote to McLaury about taking the MRSL to the Twin Cities. Impressed with the route he suggested that the line should pass out postcards about the Refuge rather than the Cody route. McLaury replied he thought he could do better than that, by including the Refuge in a revised MRSL guide.

Judging by the correspondence, Burlington officials were always busy, waiting for things to quiet down so they could work on the new guide. By 1931 they had contracted with an author to go “over the ground foot by foot” and delve “into the history of each town and city,” but they were not entirely happy with his work.

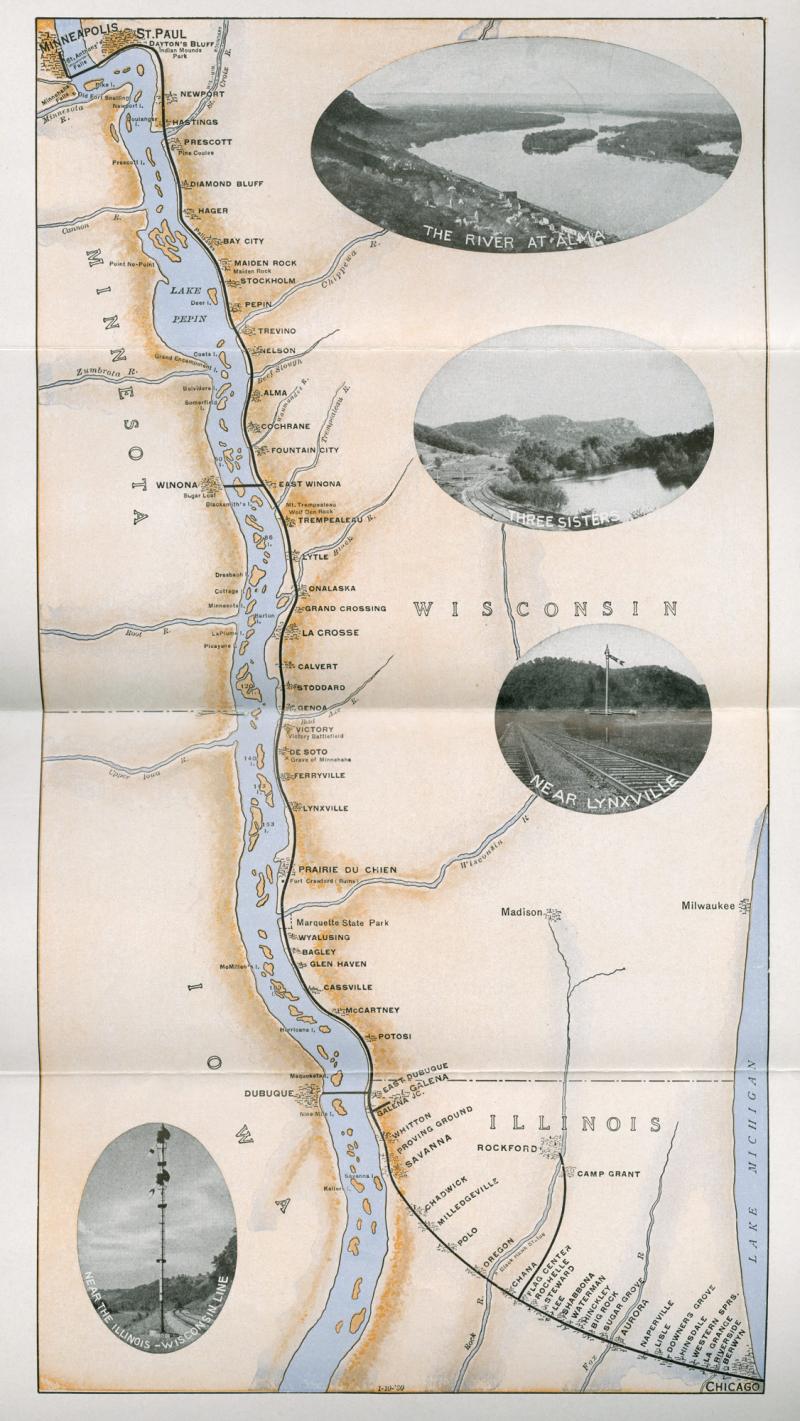

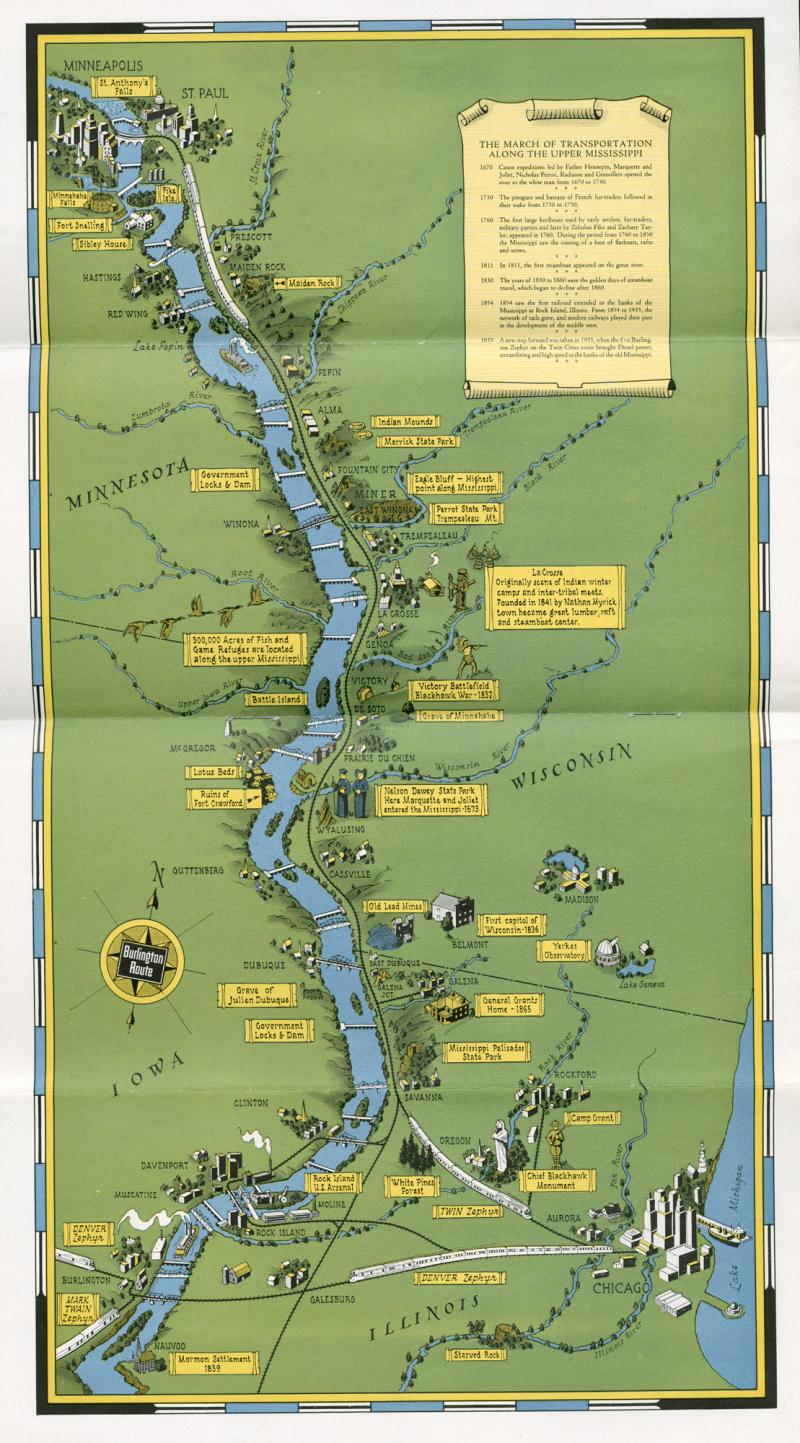

Map from Mississippi River Scenic Line brochure, 1934.

Map from Mississippi River Scenic Line brochure, 1934.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

Despite plans to significantly revise the Mississippi River Scenic Line passenger guide, the 1934 printing was not radically different from the 1907 guide. At least in the northbound, Chicago-Twin Cities version, there is no mention of the Upper Mississippi Wildlife and Fish Refuge and the text is essentially the same as the previous several versions.

On the cover a steamboat and steam engine race around a bend in the river and the road toward the viewer. The steamboat conjures images of Mark Twain and an idyllic past; the steam-powered train would soon be overtaken by the new diesel engines. Perhaps that is why the Burlington waited for a full revision of their brochure. The slogan, “Where Nature Smiles Three Hundred Miles” may have been a nod to the wildlife refuge.

The map in the 1934 Scenic Line brochure distorts the perspective, making Wisconsin and Illinois too narrow and too long, with the effect of shortening the distance between Chicago and Savanna, Illinois, and emphasizing the river and the Mississippi River Scenic Line route. Photo insets show a panoramic view of the river emphasizing islands, the “Three Sisters” bluffs, and a couple of points along the track. Using the map a passenger could identify villages and islands in the river. Points of interest include Black Hawk’s statue, near Oregon, Illinois; the “ruins” of Fort Crawford, near Prairie du Chien; the “grave” of (the fictional) Minneheha; and the “Victory Battlefield” near Victory, Wisconsin. Otherwise known as the “Battle of Bad Axe,” it marks the massacre of about 150 Sauk and Meswaki Indians, the tragic end of the Black Hawk War in 1832. Indian Mounds Park, St. Anthony Falls, and Minnehaha Falls are shown in the Twin Cities area.

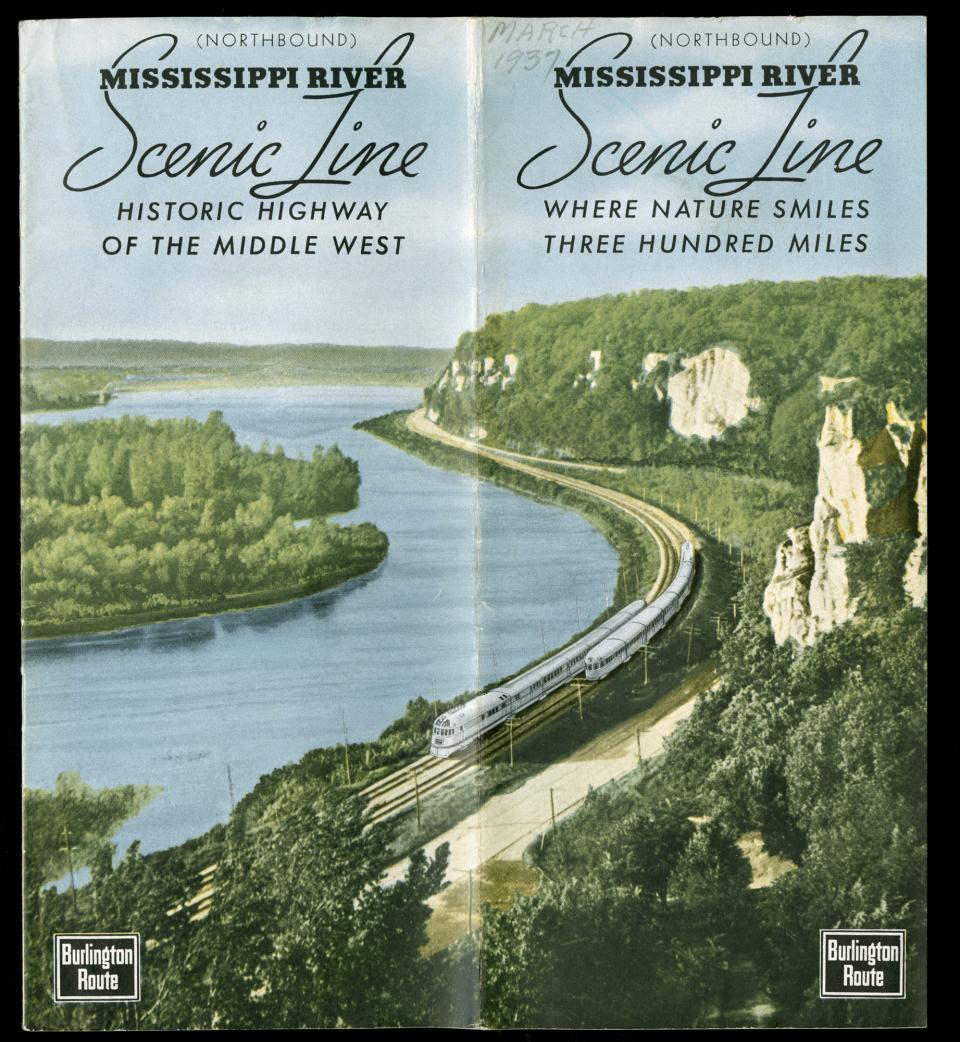

Cover, CB&Q Mississippi River Scenic Line brochure, 1937.

Cover, CB&Q Mississippi River Scenic Line brochure, 1937.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The main theme of the revised version of the MRSL guide is progress, but in historic context and in the wilderness setting of the recently established wildlife and fish refuge. The verdant cover features two Twin Zephyrs passing each other on a bend in the river, one heading north, the other heading south towards the viewer. Inside there is an essay by award-winning Chicago travel writer Lucia Lewis. The old paddlewheel boat from the previous version is gone, but Mark Twain is mentioned on five of the six pages of Lewis’s essay. The three hundred thousand acre Upper Mississippi Wildlife and Fish Refuge, protected by a law signed by President Coolidge in 1924, is mentioned several times:

Though we pass many interesting towns and cities on the Burlington Route, vast spaces of the river’s territory are and always will be unspoiled wilderness. Threatened for a time by a plan to drain the famous Winnesheik Bottoms along the Wisconsin shore, the area was saved by the efforts of the Izaak Walton League.

Cover, CB&Q brochure for the Mississippi River Scenic Line, “Where Nature Smiles Three Hundred Miles,” 1937.

Cover, CB&Q brochure for the Mississippi River Scenic Line, “Where Nature Smiles Three Hundred Miles,” 1937.

Courtesy of Newberry Library. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

The Burlington’s promotion of preservation complicates the image of railroads’ role in regional development. While in the next section Lewis wrote about a massive government lock and dam project, and the eleven dams visible between Savanna and St. Paul, which created popular fishing and hunting spots, this is followed by another reminder that “the past can be recalled without any effort by the Mississippi traveler because the Upper Mississippi Wildlife Refuge preserves much of the land as it was known to the original Indians and early explorers.”

Map of Mississippi River Scenic Line, 1937.

Map of Mississippi River Scenic Line, 1937.

Courtesy of Newberry Library Chicago. CB&Q Misc. Bx. #3.

Used with permission of the Newberry Library. With questions about reuse of this image, contact the Newberry Library.

The copyright holder reserves, or holds for their own use, all the rights provided by copyright law, such as distribution, performance, and creation of derivative works.

There is a sympathetic account of the Blackhawk tragedy and a skeptical mention of Minnehaha’s grave. Lewis also wrote of Old World influences: the village site “chosen by German settlers because the Mississippi scene reminded them of their beloved Rhine”; Genoa, the “colorful town reminiscent of the Mediterranean”; and how “the Indian, the French, the British, the Americans and all the nationalities making up our country left their mark upon this beautiful land, which remains beautiful in an age of often ugly industrialism.”

Following the Lewis essay is the familiar point-by-point guide, starting with Aurora—the birthplace of the Burlington company—and ending with the Twin Cities. The guide is updated, expanded in parts, and includes a section on the Wildlife Refuge.

Technically and aesthetically, the 1937 map is an improvement over the relatively crude 1934 map. It adopts the same distorted perspective to effectively emphasize the river route. Note the inset, “The March of Transportation Along the Upper Mississippi,” which boldly traces the progress from the birch bark canoes of the explorers Marquette and Joliet in 1670 to 1935 when “the first Burlington Zephyr on the Twin Cities route brought Diesel power, streamlining and high speed to the banks of the old Mississippi.”